The Australian

by Greg Sheridan

As Syria groaned under the dictator’s bombs and the military campaigns, well intentioned or the reverse, of the outside powers, as Egypt grieved over the horrible sectarian suicide bombing of a Christian church, as Libya grappled with the lawless, violent factionalism that has replaced Muammar Gaddafi — all of this misery rolling out of the Arab Spring — this week I witnessed an altogether different scene in the heart of the Arab world.

I was delayed checking into a mid-range resort hotel by a large, voluble group of French family holiday-makers, arguing good naturedly with check-in staff over why their rooms were not ready.

Apart from the striking, glorious, international domesticity of the scene, what was remarkable was that the holiday-makers were part of a much bigger group of Jewish visitors seeking their two weeks of summer sun and sand and buffet breakfasts. Their incidental religious affiliation was instantly recognisable because almost all the men were unselfconsciously wearing Jewish skullcaps.

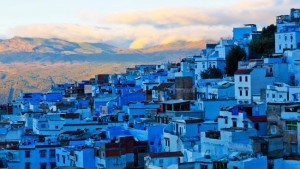

Where was this oasis of intercommunal harmony and innocent bourgeois holiday-making? Marrakesh, the fabled cultural jewel of Moroccan antiquity, that’s where.

Of all the Arab states of North Africa and the Persian Gulf, none has a serious case for emerging from the Arab Spring in better shape than Morocco. Its economic growth rate is better than 4.5 per cent; it has had two democratic elections ultimately producing stable governments; it has free trade agreements with the US and Europe; its society is functioning; it is a stable military ally of the US; its last significant terrorist attack was in 2011 (in Marrakesh). And it wants a new and more intimate relationship with Australia.

How did all this come about?

I ask this of Nasser Bourita, Morocco’s foreign minister, a man of singular charm and urbanity. A career diplomat, he has just been appointed foreign minister by the newly formed coalition government, dominated by a notionally Islamist, though certainly moderate, party.

I am the first journalist to interview him as foreign minister and we meet in his vast office in Morocco’s capital, Rabat, overlooking the green fields and surviving walls of the ancient Chellah site, first a city under the Phoenicians, long before the birth of Christ, then settled by the Romans and later the Berbers and Arabs and all who prospered under them.

“I think there were many reasons,” Bourita says. “Many observers from Australia or the West tend to think of the Arab world as a single bloc. But it’s not the case. Every country is different. Morocco is not Libya, which is not Yemen, which is not Saudi Arabia. Morocco was a state for more than 13 centuries.

“This dynasty (of His Majesty King Mohammed VI) has been here for more than three centuries. Morocco for all this time was a sovereign state and a monarchy except for 40 years of the French presence.”

The contrast, though the minister doesn’t draw it, is with most of the rest of the Arab world, which had centuries of Ottoman dominance followed by European colonisation. When Mohammed VI ascended the throne, says Bourita, he explicitly sought to modernise Morocco with a new vision of a developed, modern and moderate nation.

“For Arab countries, the question was whether historical legitimacy was enough for the future. His Majesty brought a new social contract,” Bourita continues. “He chose stability through reform.

“There were some (in the region) who believed stability could be achieved through the status quo, through freezing everything. Our stability was achieved through a new constitution, through transitional justice, through improvement in the status of women, through big projects for human development.”

Taken together with the calming influence of a popular monarchy over a republic in the Middle East, these factors do offer a persuasive explanation for Morocco’s relative success and peace. They do not, however, necessarily offer that much guidance for nations that may not have the benefits of 13 centuries of sovereignty and a prestigious monarchy.

Nor has everything been perfect in Morocco. Not far short of 3000 Moroccans found their way to Syria to fight for Islamic State.

Morocco is neither complacent about its own problems with Islamist extremism, nor indifferent to the problems of its regional neighbours.

The same day I meet the foreign minister I spend the morning at the Mohammed VI Institute for the Training of Imams, also in Rabat. This large, white, elegant campus was built in direct response to the rise of the terrorist movement and a number of terror bombings in Morocco more than a decade ago.

I am taken on a tour by the institute’s director, Abdesselam Lazaar, a sprightly, genial man of 70 summers.

The first things I notice about this commodious campus is that it is international and coeducational. The institute caters to students from Morocco, Nigeria, Senegal, Ivory Coast, Chad, Mali, Guinea and France. And while there are more young men than young women, there are plenty of young women. It seems that while women do not become imams in the sense of leading formal prayers in the mosque, they do many other jobs associated with the mosque.

The students are taught in their respective national groups because, apart from the common need for Arabic for the Koran, the students need to be taught in the language of their home nation. I am invited to stick my head into many classes and each is co-ed. This, I am told, is strikingly unusual in such an institution.

In some classes the boys are down the front and the girls up the back; in others the seating seems more egalitarian.

I am invited into the mosque to witness students memorising verses of the Koran and here, while the boys are in one group and the girls in another, the two groups are beside each other. Neither is privileged over the other.

Even more surprising, perhaps, for an institute devoted to training imams, the students study a professional or trade syllabus as well as a religious one, for the benefit of those who may end up not being imams after all. They can choose a range of professional qualifications, from electronics to agriculture to sewing.

The institute, which has been going only a couple of years, has graduated 1800 men and 700 women.

Lazaar is softly spoken, quietly proud of his students. “One of the main objects of this institute is to correct the extremist reasoning and understanding of religion,” he explains. “The extremists misuse religious reasoning for extremist purposes. This institute corrects the reasoning of extremists. Then the extremists can talk only with weapons. One day the extremists will understand they have nowhere left to work because this institute has filled their space.”

The state is heavily involved in religion in Morocco. Anyone who wants to become an imam in the future in Morocco will need to go through Lazaar’s institute. Imams are paid a salary by the state and there are limits on what they can say. His institute has taken international students at the request of neighbouring governments. Morocco foots the bill for everyone.

A day or two later, across the street from Rabat’s magnificent, ancient Medina, which sits watchfully, timelessly, over the sea, I meet Ahmed Abbadi, from the League of Religious Scholars.

Like many Moroccan intellectuals, he criticises the West for its failure to regulate, or at least involve itself, in religious practice.

Bourita, the foreign minister, refers me to men such as Lazaar when I inquire about extremism.

He thinks counter-terrorism and security is one area where Australia and Morocco could co-operate even more closely than they already do.

Canberra has recently announced it will soon open a resident embassy in Morocco, which will go some way to filling the gaping hole of our representation in this part of the world.

But Bourita envisages a much broader partnership. He thinks the relationship has a substantial unrealised potential.

“We have very good relations already but we are not maximising our potential. There is much more we could do together on investment and people to people exchanges.

“We agree on many things but there is a lot still to share in political dialogue, in sharing our assessments of our region and your assessments of your region.”

As Humphrey Bogart once remarked in a famous Moroccan scene: “This could be the start of a beautiful friendship.”

Greg Sheridan visited Morocco as a guest of the Moroccan government.