Stratfor

Analysis

Forecast

Losing money fast amid low energy prices and declining output, the Algerian government will work to trim its expenses.

Despite popular pressure to ease up on austerity measures, Algiers will have no choice but to continue implementing its much-needed reforms.

Algeria will look to foreign investors for help in overhauling its energy sector, making incremental progress toward liberalizing its economy in the process.

Analysis

Since the Arab Spring swept across North Africa in 2011, Algeria has been an immovable anchor in a region struggling to find stability in the face of wave after wave of change. Many of Algeria’s Mediterranean neighbors, including Tunisia, Egypt and Libya, are still recovering from the cataclysmic upsets that political and economic reforms have brought over the past six years.

Morocco, meanwhile, has just reclaimed its seat in the African Union after a decades long absence, and it is working furiously to re-engage with its African neighbors while preserving its friendship with the West. Morocco’s quest to improve its standing on the African continent could soon pose a threat to its longtime rival, Algeria, if Algiers does not move quickly to match Rabat’s ambitions.

But unlike its neighbors, Algeria has kept a fairly steady course in the two decades since its bloody civil war ended. Despite serious and persistent health issues, President Abdelaziz Bouteflika has held onto his seat in power. The country’s approaching parliamentary elections — the sixth since Algeria adopted a multiparty political system in 1989 — will do little to empower the legislature to mount a more effective challenge to the longtime leader and his entourage.

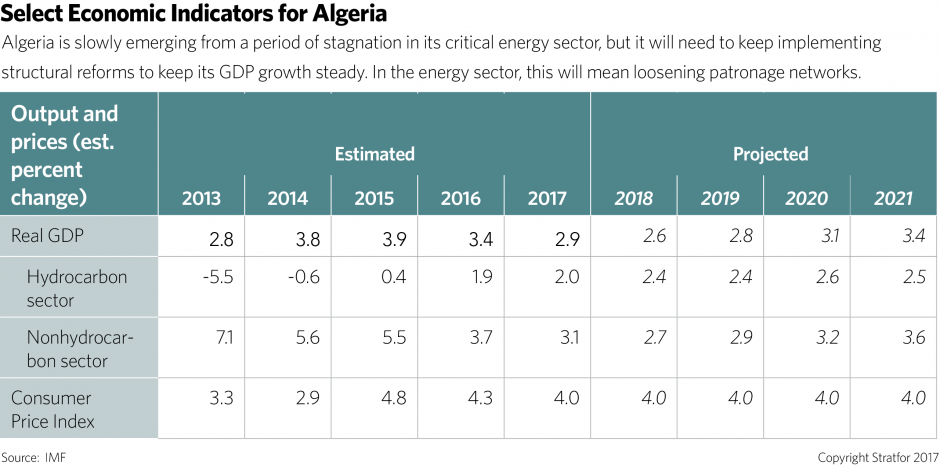

Even so, change is on the horizon for Algeria’s economy, despite the government’s reluctance to risk the unrest reforms would likely bring. The country’s economic growth and diversification have lagged in recent years, and in the face of persistently low oil prices and declining output, Algeria cannot afford to delay the overhaul of its lucrative but flagging energy sector any longer. And as it cautiously reshapes its economy, Algiers will gradually abandon its historical preference for isolation by courting foreign investors — a shift that could someday lead to a more open foreign policy as well.

Time (and Money) Is Running Out

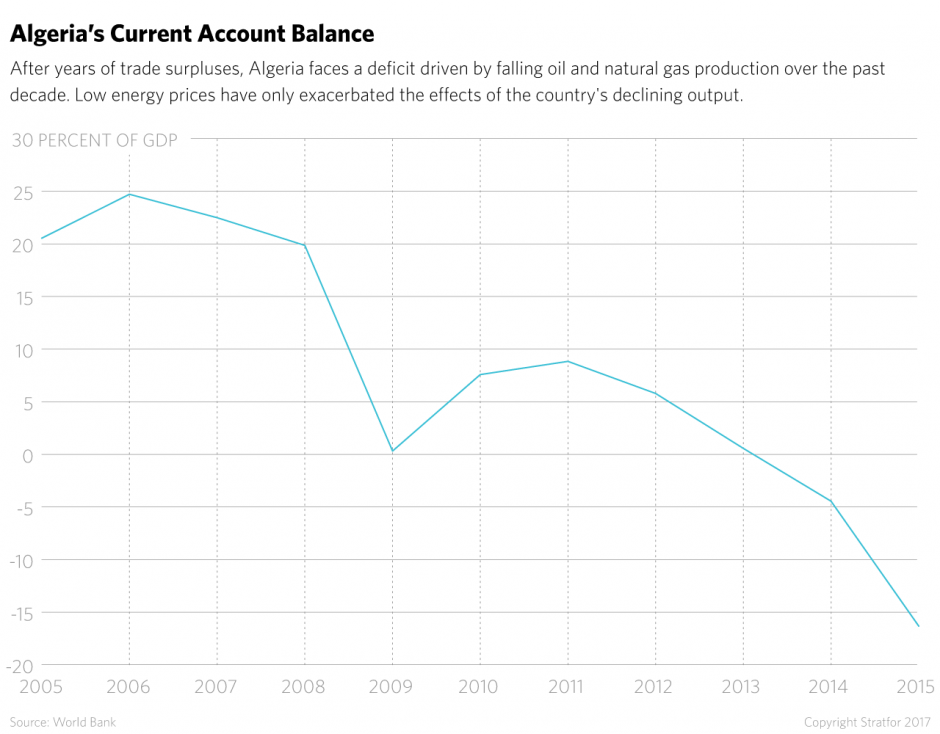

Few North African economies can claim to be faring well at the moment, but Algeria’s financial problems are especially burdensome. The country depends on oil and natural gas for 94 percent of its total exports (most of which go to Europe) and 60 percent of its budgeted revenues. When oil prices plunged in 2014 before leveling out below $40 per barrel, Algiers was forced to drain its coffers to keep paying for its imports, pushing its budget deficit to a record high of 16.4 percent of gross domestic product in 2015. Of course, Algeria still holds a massive amount of oil wealth, boasting a higher GDP per capita than even its more diversified competitor, Morocco. But high levels of income inequality continue to plague the country.

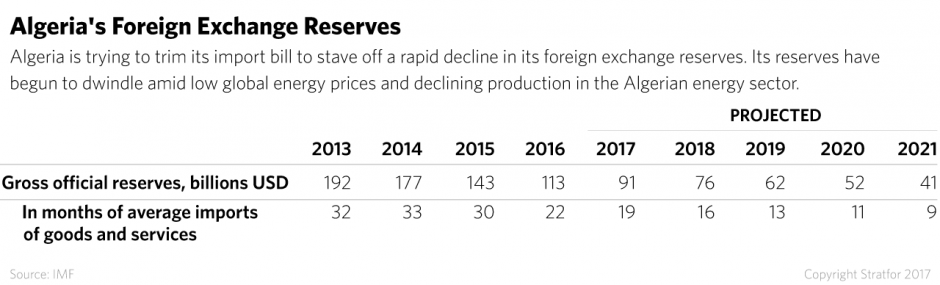

Algeria’s foreign exchange reserves, moreover, are being rapidly depleted. Tucked away in the Revenue Regulation Fund, these reserves currently stand at just over $112 billion, down from $143 billion in 2015 and $177 billion in 2014. According to the International Monetary Fund, this figure will probably keep falling in the years ahead, dropping to $91 billion in 2017 and to $76 billion in 2018.

Keeping Up With the Times

Algeria’s spending decisions over the past few years matter less than the choices it makes next. Algiers will have to funnel some of its oil wealth into diversifying the economy, even as it keeps existing social spending programs and state industries afloat. (It will also maintain its defense spending, which the government is not eager to shrink amid its ongoing rivalry with Morocco.) Despite being Europe’s second-largest supplier of natural gas, behind only Russia, Algeria has had a tough time making ends meet as prices and demand in Europe have dropped. Declining output in Algeria’s own energy sector over the past decade has only made matters worse.

The government has dipped into its considerable reserves to pay the bills and prop up the Algerian dinar, with the unfortunate side effect of boosting inflation. In an effort to stanch the bleeding, Algiers recently slashed its spending by 14 percent, deepening the cutback of 9 percent outlined in last year’s budget. In 2017 alone, Algeria will try to reduce its imports by $5 billion, in keeping with the more than $10 billion in imports it has trimmed over the past two years. Though Algeria intends to remedy the situation in the long run by investing in growth beyond the oil sector, it has been slow to follow through with its plan.

Part of the problem is that restructuring the energy industry would threaten the patronage networks that have been built up around Algerian oil and natural gas giant Sonatrach. Since 2007, Algeria’s consumption of oil and natural gas has risen by more than 50 percent while its oil production has fallen by 25 percent. With less oil available for export, the government’s revenues have been hit hard — as have the payouts and perks that the ruling elite dole out through Sonatrach to keep their supporters satisfied. Leaders have moved hastily to invest in shale and enhanced recovery projects in an effort to counteract declining output in oil, but so far they have had little success in turning the energy sector around. All the while, Algiers’ fears of stoking unrest by revamping the country’s long-standing economic norms have grown.

An Unsustainable Status Quo

For the first time in decades, Algeria has turned to the international community for help. Algiers is eagerly seeking foreign investment into its agricultural industry to help offset its hefty import bills and spur development in what was once a significant sector for the country. And this is but one of many small steps the government is taking to bring in money from abroad. In 2013, for example, Algeria tried to stave off drops in hydrocarbon production by reforming its regulatory laws. Though the country’s infamous rule capping foreign ownership of any business operating in Algeria at 49 percent is still alive and well, calls to remove barriers to foreign investment are growing louder.

The country’s new constitution, which was updated early last year, also includes several clauses designed to open the Algerian economy to external funding. For example, the document explicitly prohibits the formation of new monopolies and directs lawmakers to “improve the business climate” of Algeria. Nevertheless, the decrees’ vagueness doesn’t inspire confidence in the government’s ability to see them through. After all, Algeria is known for bungling one of the most expensive infrastructure projects in the world, the East-West Highway, and ultimately tripling the expected cost of $6 billion with rampant graft. (The debacle has become even more embarrassing in light of Morocco’s success in championing its own public-private infrastructure project over the past decade.)

Algeria has had similar trouble keeping its economy up to date in the realm of Islamic finance, an increasingly favored option for diversifying financial sectors in the Muslim world. Like many other Muslim countries, Algeria is toying with the idea of issuing its first sukuk, or Islamic bond that pins its value to an asset without accruing interest. But the country lacks a legal framework to support Islamic finance, an area of growth that nearby Morocco, Egypt and Tunisia have recently and readily embraced. In fact, Algeria’s entire banking sector is woefully out of touch with modern banking standards, and its central bank has a reputation for being one of the most opaque institutions of its kind in the world. Hoping to skirt these issues while still attracting much-needed investment, Algerian officials have proposed a plan to issue interest-free bonds. This would bring in the immediate funding the government needs without labeling it an Islamic finance instrument.

Over the past two years, Algerian leaders have shown their willingness to implement unpopular reforms, especially those that target fuel subsidies and taxes. Algiers has already bumped up the national sales tax from 15 to 17 percent, sparking protests in several provinces. If the government deepens its resolve to double down on subsidy cuts and tax hikes, the demonstrations could certainly grow and spread. Though Algiers is trying to pare down its massive subsidy payments, which currently top $45 billion, at a reasonable pace, Algerian citizens are unhappy with the effect the cutbacks will have on their own pocketbooks and standards of living.

The government has encountered pushback from the ruling elite as well. As Algiers moves to modernize its energy sector — and, in doing so, disrupt the entrenched patronage networks within it — high-ranking officials have taken steps to ensure that the reforms do not impact their access to state wealth. But they are only delaying the inevitable. No matter who follows in the footsteps of Bouteflika, a president known for his aversion to reform and equated with national stability, the country cannot protect the status quo for much longer.