Stratfor

Highlights

> Moroccan banks’ expansion across Africa will allow Moroccan businesses to invest and integrate better into the continent, gaining lucrative market access.

> Morocco’s economic integration with African countries — including current negotiations for a free trade agreement — will, in turn, attract foreign manufacturers to increase investments in Morocco.

> Morocco will need to address its high level of domestic unemployment to ensure stability.

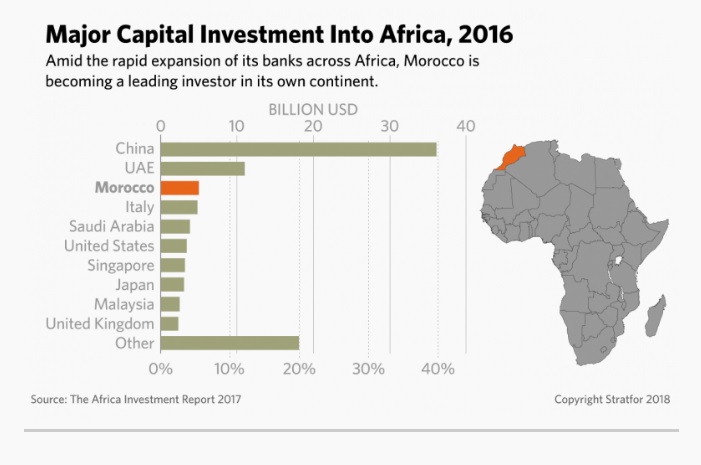

A new source of foreign direct investment is emerging in many sub-Saharan African nations: the kingdom of Morocco, situated right on the continent itself. Owing in part to quick and decisive reforms in 2011, Morocco largely avoided the Arab Spring turbulence that shook other parts of the Arab world in North Africa and the Middle East. And in recent years, solid growth in the manufacturing, tourism and energy sectors, as well as a rapidly expanding financial sector, has fueled the development of a very strong Moroccan economy. As long-dominant European banks gradually disappear from Africa, Morocco is using its newfound financial muscle to project power across the continent in the hopes of becoming a wealthier and more internationally influential country, but it still needs to address problems at home if it wants to remain one of the most stable states in Africa.

The Big Picture

Morocco is often overlooked in discussions about the Middle East and North Africa, largely because unlike several other members of the region, it has remained quite stable since the Arab Spring protests of 2011. But while Morocco perhaps doesn’t get extensive geopolitical attention, it has been quietly building its influence across Africa through enhanced economic, political and security ties.

See The Suitors of Sub-Saharan Africa

See The Difficulties of North African Reform

Morocco Makes Money Moves

Morocco’s banks have been making an aggressive push across Africa and currently hold subsidiaries and stakes in more than 20 African countries. While most of these subsidiaries are in West Africa, the 2016 purchase of Barclays Egypt by Morocco’s largest bank, Attijariwafa, signaled Moroccan banks’ intention of expanding across the continent. Since then, Moroccan banks have been involved in acquisitions as far away as the islands of Mauritius and Madagascar. Representatives from several Moroccan banks, including the country’s second biggest lender by assets, Banque Centrale Populaire, have also indicated plans to infiltrate the financial sector of East African countries such as Rwanda, Kenya and even closely financially guarded Ethiopia.

As Moroccan banks integrate themselves more deeply across Africa, they are serving as pioneers for the large and medium-sized Moroccan companies also pursuing opportunities in promising African markets. Earlier this year, Maroc Telecom reported an annualized 9.7 percent increase in its user base to 60 million, all of whom are spread across a half-dozen countries in Central and West Africa. Meanwhile, Moroccan King Mohammed VI recently signed an agreement with Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari for a gas pipeline that will stretch across the coastline between Nigeria and Morocco. State-owned OCP, a fertilizer-exporting giant headquartered in Casablanca, has ventured further east, into a partnership with Ethiopia to build the continent’s largest fertilizer plant at a total cost of $3.6 billion. Morocco was initially planning to spend money modifying a congested port in Djibouti to be able to handle regular shipments of phosphoric acid, but a recently restored peace between Eritrea and Ethiopia may allow Eritrean ports to serve as alternatives.

What’s Driving the Push?

Morocco escaped largely unscathed from the global Great Recession, since it had only minimal integration with international financial markets. But the euro zone slowdown that followed in recent years froze the kingdom’s undiversified export sector, which heavily relied on Europe. Since then, Morocco has been reshaping its financial policy in order to diversify its income. Sub-Saharan Africa, with its exploding population, growing middle class and geographical proximity, presents an ideal opportunity.

Morocco also intends to establish itself as a major link between Europe and Africa. European businesses have watched Morocco’s African ventures with enthusiasm, eager for a new conduit into African markets. In particular, recent trade wars involving increased tariffs and the economic stagnation of developing countries have begun to threaten current auto export levels, and car companies are hoping that Morocco’s economic integration with sub-Saharan Africa will serve as a scaffold for establishing new markets. French and Italian car makers Renault, PSA Group and Fiat already have production plants in Morocco. Even the Chinese automaker BYD, backed by wealthy American investor Warren Buffett, is building a plant to manufacture cars in the city of Tangiers. Morocco, for its part, is luring them by offering five years of subsidized land and tax breaks in exchange for setting up new plants.

Morocco’s economic integration with other African nations does require some compromises, and the country is reinforcing its economic push with political efforts. In 2017, King Mohammed, known for his marathon diplomatic tours, successfully lobbied for his country to rejoin the African Union decades after it stormed off to protest the group allowing membership of Western Sahara as an independent state. Despite disagreements with the African Union on the status of the disputed Western Sahara, Morocco’s recent return shows that the government in Rabat, the capital, is making a strategic shift, looking beyond securing its geopolitical interests while focusing on economic influence in Africa.

And in 2017, the kingdom applied for membership in the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), a regional union composed of 15 countries. As the union presses on with a trade liberalization scheme, full membership for Morocco would facilitate exports to member countries by eliminating existing barriers. For the moment, however, Nigerian trade unions are lobbying against admitting Morocco out of fear of being dominated by experienced and technologically advanced Moroccan multinationals. Other members of the bloc have also demanded that the kingdom ease its travel restrictions for citizens within the ECOWAS. This would make some European nations uncomfortable, as it would likely encourage more West Africans to travel to Morocco in hopes of illegally crossing over to Europe.

But a currently in-progress African continental free trade agreement would dwarf any existing or proposed trade agreements between Morocco and other countries. Last March, a delegation from Rabat attended a signing ceremony in Kigali along with representatives from 44 other African nations. That free trade agreement will need a minimum of 22 countries to ratify its terms before it goes into effect.

The Risks of Progress

European banks have been divesting from Africa for reasons including increasing regulations over high-risk assets and falling commodity prices, and this development has taken a toll on several African economies. By contrast, Moroccan banks are showing an increased interest in Africa — and are displaying a correlative bigger appetite for risk, exposing themselves to low-grade domestic sovereign bonds in countries that rely on commodity exports. This behavior can be attributed in part to Morocco’s competitive domestic market, which provides little room for the kingdom’s ambitious banks to grow.

However, a 2017 report by rating agency Fitch highlighted the reality that Moroccan banks’ eagerness to invest in African countries, their low capital buffers and their weak asset quality all make them particularly susceptible to economic volatility. Currently, close to a third of total profits earned by Moroccan banks are generated from subsidiaries across Africa. Even if Morocco’s domestic capital markets remain strong and its public debt remains low, any future recession that affected Africa’s economies would expose the banks to significant losses and put Morocco in a much less comfortable position than it was a decade ago.

Another barrier to Morocco achieving its goal of gaining international influence is the country’s worsening unemployment rate — especially for younger citizens. Moroccan youth unemployment rates stand at 27 percent, almost triple the national rate. And as appealing as the rapid cross-border expansion of banks and telecom may be to the Moroccan government, these investments abroad don’t have any direct benefits for younger Moroccans seeking immediate employment. In the past, dissatisfaction among unemployed youth has boiled over into mass protests.

Policymakers in Rabat appear to recognize the urgent need to include unemployed youth in their development agenda, and in recent years they have reduced energy subsidies to divert funds toward bolstering employment. But if Rabat is unable to make significant progress and ease areas of potential unrest, it may have to put its more ambitious continental expansion goals on the back burner to address domestic instability.