The Hill

By Ahmed Charai, opinion contributor

The views expressed by contributors are their own and not the view of The Hill.

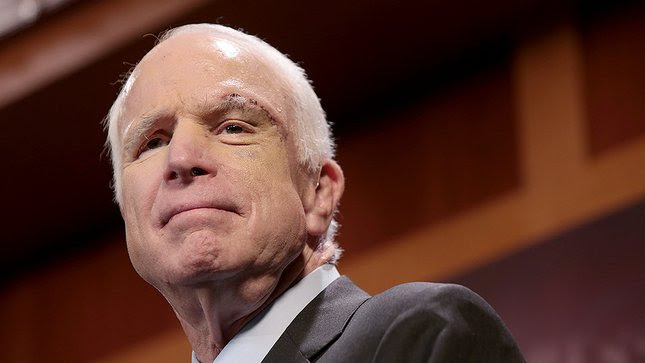

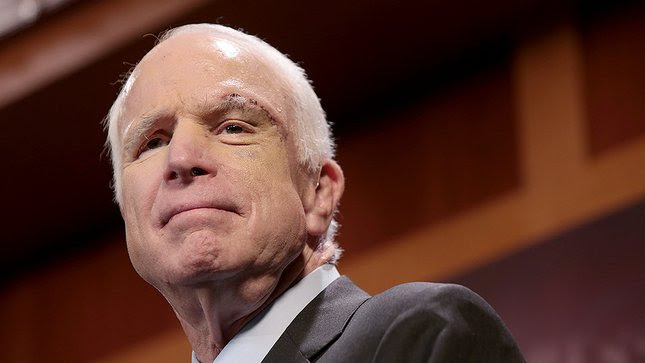

While you’ve probably already read your share of encomiums for that extraordinary American patriot, John McCain, you probably haven’t heard about the lives he saved in Arab and African lands, like mine.

Far from the camera’s eye, in places where no one could vote for him, late-Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.) took political risks without any corresponding political benefit to himself. I saw him in action in Africa, Europe and the U.S. and had more than a dozen meetings with him over the past decade. I saw a side of him that you never saw.

Consider the case of the more than 400 Moroccan prisoners of war, held in miserable conditions, in internment camps deep in Algeria’s Sahara. Their captors were the Polisario Front, an Algerian-backed, pro-Marxist group that aimed to break off the southern half of Morocco and rule it as a one-party state in the name of Saharan tribes that have lived there for centuries. (Morocco’s legal claim is even older, going back to the early Middle Ages when the Arabs first arrived in North Africa’s westernmost reaches).

The Polisario Front carried out bombings across Morocco in the 1970s and 1980s; its fighters assaulted army barracks and police stations — often taking captives for ransom. Others were held as political pawns. For some, their captivity dragged on for decades, while the children grew up without them and their wives longed for reunification.

Finally, in 1991, the Polisario Front signed a treaty agreeing to return the men captured on Moroccan soil and frogmarched to their remote desert camps near Tindouf, Algeria. Yet, despite the 1991 treaty, the separatist group kept its captives.

Senator John McCain knew something about captivity. He has been beaten, tortured and squeezed into “tiger cages” too small for him to stand or lie down by the communist North Vietnamese for five long years. When he heard of the plight of the Moroccan POWs in 2005, he publicly and repeatedly demanded their release.

He had nothing to gain politically. The Arizona voters who repeatedly elected him to the U.S. Senate had largely never heard of the Polisario Front and the American press rarely, if ever, mentioned the ordeal of the Moroccan POWs. Yet, McCain persisted, demanding their freedom.

He won. On Aug. 18, 2005, the Polisario Front finally released the Moroccan POWs to the Red Cross. They were flown to Agadir, on Morocco’s Atlantic coast, aboard a U.S. piloted aircraft. On the runway, they were welcomed by King Mohammed VI.

It was a big moment in Morocco. Wives embraced their husbands for the first time in 30 years; fathers were reintroduced to their children, last seen as infants, who now had children of their own. The nation wept for joy.

The king of Morocco, Mohammed VI, never forgot McCain’s incredible role. He sent official condolences to the senator’s family. He acknowledged his country’s debt to this former prisoner, the senator from Arizona.

Or consider the case of the Congo, another nation where McCain quietly made his mark. When the president of Democratic Republic of Congo (once known as Zaire), Joseph Kabila, publicly mulled violating his nation’s constitutional ban on serving more than two terms in the presidency, protests erupted. Africans were tired of strongmen who ruled for life, as Kabila’s father had and as had his predecessor, Mobutu SeseSeko.

The Congolese demonstrated for much of 2015 and 2016.Kabila’s police forces killed some 40 demonstrators, severely beating many hundreds more. In Congo, the question became: Which would prevail, the president or the constitution?

McCain knew there were plenty of reasons for the U.S. to be concerned: Congo dominates central Africa — a sprawling state as large as Western Europe — with strategic minerals vitally needed for the U.S. military and Silicon Valley, and a large population that, if set in motion, could instantly create a refugee crisis that would dwarf Syria’s. Already the nation of 70 million had lost more than 6 million to civil war—a loss on the scale of World War II.

By contrast, if the U.S. could help secure a smooth transfer of power to a democratically elected successor, Congo would become a shining example for the developing world.

The stakes were high and McCain was one of the few in Washington to grasp the situation.

Writing to Congo’s ambassador to the United States, McCain expressed his “deep concern at the increasingly repressive political climate and erosion in the human rights situation.” He talked about the rule of law and upholding the Congo constitution.

McCain was not deterred. He continued to press constitutional change in Congo until he died. In the days before the senator’s death, Kabila announced in August 2018 that he will not run for an unconstitutional third term, when elections are held in December. Again, McCain had won.

As I got to know McCain from 2005 onward, I got to know a rare public official who didn’t calculate the advantages to himself. It didn’t boost his chances of reelection or raise his popularity. He just did it because it was right.

McCain’s commitment to peace, democracy, human rights transcended political divisions. When he happened to vote against his own political party, I knew that his convictions had driven him there. We had many conversations at the Atlantic Council, and at the CSIS where we both served, in Washington D.C. In all of our meetings, he was passionate about strengthening democracy and human rights across the Arab world.

The McCain meeting that marked me most was on February 19, 2011 in Rabat, Morocco’s capital. The day before, street protests heralded the start of “the movement of February 20.” This was the Moroccan chapter of the events that Americans call “Arab spring.” These protests, and their ominous portents, were the background music, when he sat for an interview with me.

At the interview’s end, he asked me, with real concern in his voice: “Are you afraid for your country?”

He had seen what damage “Arab Spring” had wrought in Egypt, Syria, Tunisia and Yemen. He worried about chaos marching into my quiet, prosperous country.

We may not see another like him in our lifetimes. Both your country and mine is fortunate that we had his character and his conviction when he did. The world without him would have been far different.

Ahmed Charai is a Moroccan publisher. He is a board directors of the Atlantic Council and an International counselor of the Center for a Strategic and International Studies in Washington.