Kuwait security forces have on several occasions used what appears to be excessive force to disperse largely peaceful protesters at a series of demonstrations over participation in the country’s political process since October 2012. Some demonstrators have been wounded, and the security forces have arrested many more.

In several statements the Interior Ministry justified the use of force on the grounds that protesters had blocked traffic, thrown stones at the police, and attacked them. However, Human Rights Watch interviewed more than 20 protest organizers, participants, rights activists, and witnesses, who said that demonstrations they took part in or witnessed were largely peaceful. They said that masked riot police used tear gas and sound bombs without warning to disperse demonstrations and beat protesters while arresting them for participating in “unauthorized protests.”

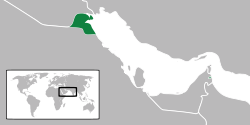

Kuwait

“There is no justification for attacking peaceful protesters,” said Eric Goldstein, deputy Middle East director at Human Rights Watch. “The authorities should show they will not tolerate abuses by investigating all allegations of abuse by security forces and punishing those responsible for violating rights.”

Since mid-October, online activists and opposition groups have organized numerous demonstrations in various parts of Kuwait, protesting a decree by Emir Sheikh Sabah al-Ahmad al-Sabah and an election process that they said undermined their rights. The government initially banned all protests, then rescinded the decision.

The Kuwaiti authorities should respect the right to freedom of peaceful assembly and investigate police use of force during the demonstrations, Human Rights Watch said. If force is required to stop violence by demonstrators, security forces should use the minimum force necessary to carry out lawful objectives.

Kuwait should increase the accountability of its police forces by ending the use of masked anti-riot forces who wear no badges identifying themselves, Human Rights Watch said. While police agents may have legitimate reasons to mask their identities in limited circumstances, such as when conducting surveillance, policing demonstrations is not one of them.

The political crisis in Kuwait began in June, when the emir suspended parliament for a month. The Constitutional Court then dissolved parliament but on September 25 rejected a government motion to amend the country’s electoral law. On October 7, the emir set December 1 for an election for a new parliament.

On October 19, the emir decreed amendments to the electoral law that reduced from four to one the number of votes each voter could cast. Opposition groups, including Islamists, liberals, nationalists, and tribal elements, condemned the move saying it had violated the constitution and that the electoral law should be amended only by an elected parliament.

Security forces used force and made arrests at several demonstrations, the protesters and witnesses said. On October 15, protesters said, security forces beat protesters near parliament after some protesters tore down a barrier. Security forces used teargas and sound bombs to disperse a demonstration on October 20 in Abraj and another on that date at Tahrir tower in Kuwait City. Security forces also used teargas and sound bombs at a demonstration on November 4 in Mishrif.

On October 21, the Interior Ministry issued a statement saying it would only allow protests at al-Irada Square, across from the National Assembly (parliament) building in Kuwait City, then permitted demonstrations on November 30 and December 8, both of which ended peacefully.

Article 21 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which Kuwait ratified in 1996, states that “the right of peaceful assembly shall be recognized,” and that “no restrictions may be placed on the exercise of this right other than those imposed in conformity with the law and that are necessary in a democratic society in the interests of national security or public safety, public order, the protection of public health or morals or the protection of the rights and freedoms of others.”

Kuwait’s constitution guarantees the right to freedom of assembly. In 2006, the constitutional court struck down 15 of the 22 articles of the 1979 Kuwaiti Public Gathering Law, including article 4, which requires permission to hold public gatherings. However permission is still required for marches.

“Kuwait’s rulers need to fully respect the right to assemble peacefully,” Goldstein said. “Declaring a gathering “unauthorized” does not give police license to beat protesters.”