Global Risks Insights

by Anas Abdoun

A bleak economic outlook and years of falling oil prices have set the stage for popular unrest in Algeria. The country also faces major security challenges, including the presence of terrorist groups, porous borders, and the threat of contagion from neighbouring Libya and Mali.

This GRI Special Report looks at how the situation reached a crisis point, and where it is heading.

The oil crisis

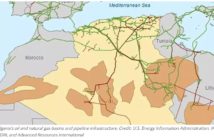

Algeria invested heavily in its oil and gas industry in an effort to grow its exports to Europe, which represent 97% of its export revenues and 60% of the state budget. Then the oil price began to fall on world markets – with devastating consequences. Algiers lost 30% of its total budget, and in 2015 was forced to implement austerity measures for the first time. To soften the blow, the government decided to use the national sovereign fund to balance the budget, but after two more years of low oil prices, the fund has all but dried up.

Making matters worse, Algeria’s oil and gas reserves are nearly exhausted, and production decreases each year. The government tried to buy time by prospecting new oil and gas reserves in 2016. State-owned energy firm Sonatrach claimed to have discovered 32 new potential exploration zones.

However, most new fields are shale gas, located in southern Algeria. Shale gas extraction requires huge quantities of water, in order to perform hydraulic fragmentation. In a country well below the UN water poverty threshold and one of the driest in the world, this is unlikely to be a long-term solution, especially in view of widespread protests.

In the best possible scenario, Algeria could produce gas at current rates until 2030. This gives the country only a little over a decade to find alternative sources to fund 60% of its budget revenue.

From oil crisis to economic crisis

Algeria urgently needs to diversify its economy, but faces a number of obstacles. The gutting of the sovereign wealth fund has curtailed the country’s ability to invest domestically. Algerian private enterprise, marginalised by the state’s focus on the oil sector, suffers from lack of competitiveness. The underdeveloped tourism industry has been labelled as a top-five priority by the government, but continues to stagnate amid insufficient promotion and long-term vision.

Meanwhile, excessive bureaucracy and lack of supportive legislation are a major obstacle to foreign investment, even for large multinational groups. All too often, investment flows to neighbouring Morocco instead. French automotive group Renault, for example, did invest in a small factory in Algeria, but positioned its biggest foreign factory complex in Morocco. Similarly, although Chinese construction companies have taken up a few Algerian public contracts, such as the Great Mosque of Algiers, Morocco is a much more important partner with $10 billion of investment in the ‘Mohamed VI Tangier-Tech’ project alone.

Running out of options

It’s increasingly clear that Algeria is falling behind even its resource-poor neighbours, and that the wealth of the country has been mismanaged by the ruling elite: the Panama Papers scandal revealed the vast scale of corruption between the government and Sonatrach. President Abdelaziz Bouteflika’s ill health has made it even more obvious to Algerians that real power is not in his hands, but shared between the military, the ruling National Liberation Front (FLN) party, and the DRS secret services.

This has in fact been the case since the independence of the country in 1962. At first, the government derived its legitimacy from its role in the War of Independence; in the 1990s, it buttressed its power using the war against terrorism. With the growth of oil prices in the 2000s, the ruling powers used oil revenues to appease the population’s demands for progress, employment, and social freedoms. During the Arab Spring, Algeria sought to avoid unrest by means of massive redistribution of wealth by the government. And six months ago, when a protest movement arose in Kabylie region against the 2017 budget, the minister of interior announced a $10 billion plan to preserve Algerians’ purchasing power.

But as state coffers grow ever-emptier, the ruling elites are running out of options to contain social unrest. And Algerians have plenty of reasons to be dissatisfied.

A perfect storm

The oil crisis of the 1980’s and the inflation that followed were key contributing factors to the ensuing civil war between the government and Islamic groups, which caused more than 200,000 deaths. All the ingredients that led to civil war in the early 1990s are present in Algeria today: a major economic crisis, the corrupt FLN, Islamic leaders still preaching over corruption, and tribal identity-related tensions.

Indeed, identity issues are generating unprecedented violence, especially in the Kabylie region where the revival of the Amazigh (Berber) legacy is in opposition to the Arab and Muslim identity. Meanwhile, Ali Belhaj, a former leader of the FIS, an Islamist militant group, has increasingly been making public appearances, seemingly with the permission of the authorities. A month ago, when Ali Belhaj visited a mosque in a popular district of the capital Algiers, hundreds of people welcomed him as a hero.

Add to this Algeria’s demographics problem: most of the population is young, with an average age of 27.7 years. Not only are youth more likely to go out into the streets, but importantly, this also means that a large part of the population has no memory of the ‘black decade’ that followed the previous civil war.

The final destabilising element in this situation is the president’s illness, which has led to a power struggle within the elite – a clash of the clans.

Fatal infighting?

There are signs that a clash of clans could be taking place, involving the president’s inner circle, the oligarchs, the secret services (DRS), and the army’s chiefs of staff. To appreciate the implications, it’s essential to understand that the Algerian regime is somewhere between a military dictatorship and a police state with a democratic façade, in which alliances shift and change depending on what interests are at stake.

There are alliances between the military hierarchy and the DRS on the one hand; and the FLN, the world of finance, and powerful elite families on the other. These groupings fight over the embezzlement of billions of dollars in oil revenues, through the collection of hidden commissions on major import and export contracts. This has occasionally come to light, most recently in Italy, where a trial is ongoing over embezzlement involving executives of Sonatrach.

In short, the elites are very likely preoccupied with their own survival, detracting from their ability to address social and economic problems at this critical juncture.

A high-risk period

In a speech this September, Algerian Prime Minister Ahmed Ouyahia stated that from November onwards, the country has no option but to resort to non-conventional funding to be able to pay its civil servants. But he also confirmed that no social welfare will be cut, that pensions will increase, while taxation will remain untouched. What this means is that Algeria will keep the same pace of expenditure, with no increase in income but at the expense of increasing loans. Such policies may lead to a high inflation in the coming two years, and a decline in per capita GDP that would have negative repercussion on households.

Algeria’s stability has thus far rested on two pillars: economic growth from oil revenues, and the reluctance of older generations to relive the traumas of the civil conflict. With these pillars now weakening, Algeria is on the cusp of a high-risk period of instability.