The Washington Post

By Danielle Paquette

When thousands of troops from the United States, Africa and Europe trained together here this month, one nation was notably absent: France.

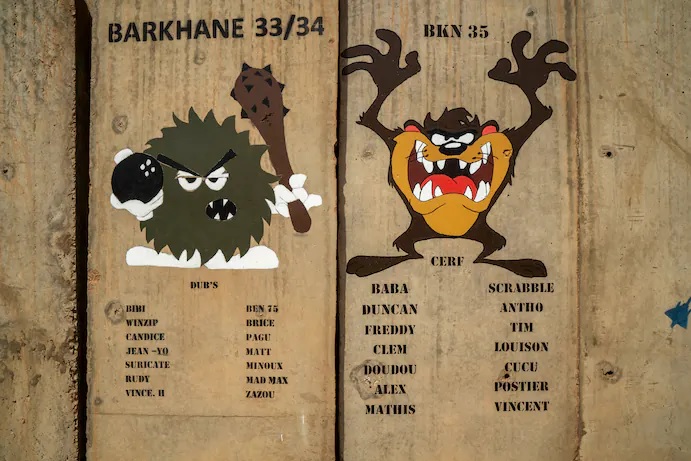

The former colonial power has for years led one of the biggest forces in the fight against extremist groups aiming to conquer land south of the Sahara. But as the United States hosted one of the region’s largest military exercises, Paris announced that its Operation Barkhane is coming to an end, a move that analysts say will upend the international community’s response to the menace at a time when violence shows no sign of abating.

The security reset raises questions about how the Biden administration will respond to rising threats across the terrain known as the Sahel, where American troops have long played more of a supporting role.

West and Central African forces say that on their own, they don’t have enough funding or equipment to protect their nations from Islamist militants linked to al-Qaeda and the Islamic State.

“We need backing and support to fight this terrorism that undermines all of our development efforts,” said a Senegalese officer who, under his military’s rules, spoke on the condition of anonymity. “We need the support of all partners. We need everyone.”

France has about 5,100 troops in the Sahel as part of Operation Barkhane, which was formed in 2014 after French forces helped stop extremists from seizing the capital of Mali.

The United States has roughly 1,100 service members in the region focused on training, logistical support and intelligence. At a news conference this week, French President Emmanuel Macron said he is asking Washington and other allies to provide special forces for a counterterrorism coalition meant to replace Barkhane.

But Western enthusiasm for that effort is tepid, and the military resources of the region’s countries are already stretched thin against “major challenges,” according to the latest U.N. Security Council report.

The French government’s stepping back could make way for China and Russia, researchers say, as both countries look to the continent to expand their global influence.

“The Russians have already signed military agreements with several Sahelian countries and are most likely to pounce on this opportunity,” said Judd Devermont, director of the Africa program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington.

Despite heavy intervention by French and regional troops for almost a decade, bloodshed continues to escalate in the Sahel.

Destroying a fragile peace, terrorists wreak havoc in West Africa

Attacks have spilled from Mali — the epicenter of the conflict, which researchers say was ignited by the 2011 collapse of the Libyan government — to its neighbors, primarily Burkina Faso and Niger.

Nearly 7,000 people died in the violence in 2020, according to the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED) — the highest annual tally yet. Burkina Faso endured its deadliest massacre in years this month when gunmen stormed a northern village, killing at least 132 people.

Security forces and community defense groups have also killed hundreds of civilians, ACLED estimates show. Innocent people are often perceived as the enemy, researchers say, or they are punished for sharing villages with fighters.

Security forces and community defense groups have also killed hundreds of civilians, ACLED estimates show. Innocent people are often perceived as the enemy, researchers say, or they are punished for sharing villages with fighters.

A troop reduction could lead to less fighting and more dialogue, said Hannah Armstrong, an analyst with the International Crisis Group.

“Deploying counterterror forces has wiped out some leaders but failed to defeat or contain the threat,” she said. “Instead, there has been a rise in authoritarian rule, a spread in instability and much higher risk to civilians.”

The war in the Sahel has become domestically unpopular for France, and concerns have grown in West Africa that the foreign offensive is hurting more than helping. Protesters in Mali and its neighbors have demanded that French troops leave.

“We do need more help to fight the terrorists, but for years, France has shown an inability to do it,” said a Burkina Faso military officer who spoke on the condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to speak to the media. “This is why the population is revolting more and more.”

Macron’s drawdown announcement came three weeks after Mali saw its second coup d’etat in nine months — a development the French leader blasted as “unacceptable.”

Military leaders are now in charge of Mali, and Western governments have cut off security assistance until democratic rule is restored. (The United Nations has a peacekeeping force of 13,000 in the country, but that group is focused on civilian protection.)

“Security has deteriorated since the last coup,” said a Malian army officer who spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of retribution. “If the French operation ends, I hope it will end only in name. We need all the help we can get here.”

Paris began seeking more European partners in the Sahel last year with the creation of Operation Takuba. That team — expected to take the reins from Barkhane — has only 600 special forces troops in Mali, mostly from France, Sweden, Estonia and the Czech Republic.

U.S. Africa Command did not say whether American troops would join Takuba, per Macron’s request. Special operations have been minimal in the region since Islamic State militants killed four U.S. soldiers four years ago in western Niger.

“We value our partnership with France and other international partners in the Sahel, and look forward to learning more over the next few weeks about France’s plans to execute this strategic shift, including their view of operational resources and coordination mechanisms necessary to implement it,” said Cindi King, a Defense Department spokeswoman.

Annual military exercises are one way allies in the region typically collaborate. U.S. soldiers share meals and run combat drills with African and European counterparts. Military doctors and nurses see patients at local hospitals — a form of diplomatic outreach that includes cataract surgery, root canals and acupuncture for migraines.

More than 7,800 troops attended this year’s two-week training event in Morocco, dubbed African Lion, the largest U.S.-run war games on the continent.Default Mono Sans Mono Serif Sans Serif Comic Fancy Small CapsDefault X-Small Small Medium Large X-Large XX-LargeDefault Outline Dark Outline Light Outline Dark Bold Outline Light Bold Shadow Dark Shadow Light Shadow Dark Bold Shadow Light BoldDefault Black Silver Gray White Maroon Red Purple Fuchsia Green Lime Olive Yellow Navy Blue Teal Aqua OrangeDefault 100% 75% 50% 25% 0%Default Black Silver Gray White Maroon Red Purple Fuchsia Green Lime Olive Yellow Navy Blue Teal Aqua OrangeDefault 100% 75% 50% 25% 0%Sandstorm surrounds journalists and troops during military trainingThe Post’s Danielle Paquette traveled to Agadir, Morocco, in June to report on France’s withdrawal from Africa’s fastest-growing conflict. (U.S. Africa Command)

On the sidelines, Maj. Gen. Andrew Rohling — commander of the U.S. Army Southern European Task Force, Africa — said the United States is sticking to its support-heavy mission, which hasn’t changed much under the Biden administration.

“I know the French are quite concerned as a military about security,” he said. “I think they are heavily committed, and we remain committed to the French.”

In Morocco’s southern desert, he said, the United States was showing off part of that commitment.

U.S. soldiers rolled through the sand one recent evening in military trucks. Built-in were rocket launchers. Blasts rang out like thunder. A group of international onlookers watched through binoculars as explosives streaked the hazy sky.

That kind of artillery — flown down from a base in Germany for this demonstration — is used to deter bad actors, a U.S. officer on the scene explained.

Thus far, no conflict has compelled the U.S. to fire one in Africa.

CORRECTION

CORRECTION

An earlier version of this article incorrectly referred to the Czech Republic as Czechoslovakia. This version has been corrected.Video shows rocket launches during military training in MoroccoThousands of troops from the United States, Africa and Europe trained together during the month of June, but France was notably absent (Danielle Paquette/The Washington Post)

Read more:

Macron announces end of major military operation in West Africa

Military officer who toppled two presidents in Mali is in charge of the country

He yearns to escape war. His best shot: Dancing to stardom.127 Comments