Qantara.de

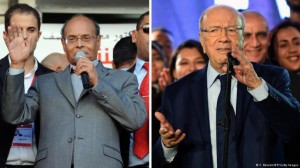

Tunisia’s outgoing and incoming presidents respectively: Moncef Marzouki (left) and Beji Caid Essebsi. According to Loay Mudhoon, Tunisia’s post-revolutionary politicians saw what exteme polarisation and entrenched ideological fighting led to in Egypt and avoided making the same mistakes

The election of veteran politician Beji Caid Essebsi as Tunisia’s first ever democratically elected president is a vital milestone on the road to the establishment of a true Arab democracy, says Loay Mudhoon.

There can be no doubt whatsoever: the election of Beji Caid Essebsi as the first democratically elected president in Tunisia’s history is truly historic in a number of ways – not only for the North African country, but also for all Arab nations currently in transition.

To begin with, this successful and surprisingly peaceful election marks the end of a difficult democratic transition in the motherland of the Arab Spring revolts.

At the same time, it confirms the pioneering role automatically assigned to Tunisia in a region scarred by post-revolutionary chaos, the collapse of states and the reform blockades set up by the incapable and authoritarian governing elites.

No one expected the transition from the long-term dictatorship of Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali to a democratic future to be so difficult. Of all the post-revolutionary Arab states, Tunisia had the best conditions for making a successful journey to democracy and the rule of law.

The country has a relatively strong civil society, a confident women’s movement, good domestic negotiating bodies, such as the Tunisian General Labour Union (UGTT), a relatively good education system and a well-functioning administration. On top of that, the military has rarely played a political role.

In addition, after the departure of Ben Ali in 2011, the transition got off to a promising start. Following the country’s first democratic elections for the assembly that would formulate the new constitution in October 2011, the winners agreed surprisingly quickly to form a coalition government and shared out the most important offices in the state.

Then, starting in October 2012, the transformation process began to stagnate. Tunisians waited in vain for the constitution that should have been in place at this time. Social and political polarisation intensified, particularly after the murder of opposition politician Chokri Belaid.

Learning from events in Egypt

However, dramatic events in Egypt showed Tunisia’s post-revolutionary elites where extreme polarisation and ideological turf battles can lead. In July 2013, following days of mass protests, the Egyptian military toppled the democratically elected Islamist President Mohammed Morsi, and summarily banned his Muslim Brotherhood – the parent organisation of political Islam. This was followed by an almost complete restoration of the old Mubarak regime. Since then, the country has been regularly shaken by terrorist attacks; economic and social crises have worsened and are threatening to make the country ungovernable.

Of course, one couldn’t expect the heavy legacy of dictatorship to be overcome without fierce social confrontation. However, the way in which Tunisians negotiated a new understanding of the state and a freely-negotiated social model has been decisive for the success of the transformation.

The Islamist Ennahda movementlearned from the mistakes of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood, which was out of its depth and out of touch with reality, choosing instead a real national dialogue. They acted pragmatically in the constitutional process and decided against including Islamist references in the constitution.

That meant that all political forces could agree on what is, in effect, the most progressive constitution in the Middle East, one which enshrines a balance between secular and religious citizens.

Now Essebsi must act

President-elect Essebsi and his secular-nationalist Nida Tounes party now face major challenges. Not only are a stabilisation of the country’s security situation and the implementation of far-reaching reforms in the security sector urgently needed, the economy, which has been on its knees since the fall of Ben Ali nearly four years ago, has to be revived.

In order to achieve this, Essebsi, who relied on the networks of the old regime in his election campaign, must effectively involve the more pragmatic and solution-oriented Islamists of Ennahda, particularly in his efforts to battle Tunisia’s ticking time bomb: high unemployment.

If he doesn’t, there is a serious danger that Tunisia’s youth will lose faith in the aims and achievements of the revolution and distance themselves from this new, hard-won social order.

Loay Mudhoon