HUFFINGTON POST

Rabah Ghezali

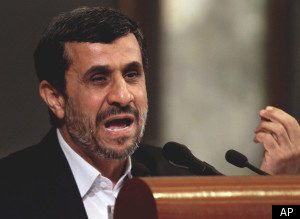

2011 started with high hopes in the Arab world. A series of uprisings toppled long-ruling dictators: with four down so far, the blood-drenched Syrian despot will surely follow his counterparts in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya and Yemen. If the uprisings were welcomed, the new regimes’ instability has fuelled anxieties. Power struggles and sectarian violence shattered illusions that the transition to democracy would be simple. To the chagrin of western commentators, democracy has ironically been detrimental of pro-democracy political parties: the electoral success of Islamists in Tunisia, Morocco, and Egypt led pessimists to suggest that an Islamic autumn has replaced the Arab spring. Contrary to earlier hopes that the Arab world would imitate Turkey’s example, many now warn that it is more likely to follow Iran’s.

2011 started with high hopes in the Arab world. A series of uprisings toppled long-ruling dictators: with four down so far, the blood-drenched Syrian despot will surely follow his counterparts in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya and Yemen. If the uprisings were welcomed, the new regimes’ instability has fuelled anxieties. Power struggles and sectarian violence shattered illusions that the transition to democracy would be simple. To the chagrin of western commentators, democracy has ironically been detrimental of pro-democracy political parties: the electoral success of Islamists in Tunisia, Morocco, and Egypt led pessimists to suggest that an Islamic autumn has replaced the Arab spring. Contrary to earlier hopes that the Arab world would imitate Turkey’s example, many now warn that it is more likely to follow Iran’s.

These anxieties are overstated. Contrary to this recent pessimism, there is strong reason to believe that the Arab spring will spread in the short term and succeed over the longer term.

Far from the Arab spring spawning the Islamic revival, the tyrannical systems that have been toppled were the seedbed of militancy. They allowed fundamentalists to persuasively argue that they stood for the downtrodden without ever having to explain how they could help them in practice. Paradoxically, dictators such as Ben Ali and Mubarak and Islamisists alike encouraged the same reductionist view that there was a choice between dictatorship and theocracy. There is no reason why western commentators should be so keen to embrace this preposterous Scylla and Charybdis.

While the Arab spring hardly created the Islamic revival, closer examination shows that Islamist parties are acting in a manner that runs against the grain of how they are routinely perceived. In Tunisia, Morocco, and Egypt, for instance, Islamist parties have not campaigned on an Islamic agenda as such but rather on the moralization of political life and socio-economic issues. They have eschewed their past rhetoric of anti-Americanism, reviving the caliphate, or wiping Israel off the map, and replaced these the dystopian Islamist obsessions with practical concerns of finance, welfare, and food. The Egyptian and Tunisian Islamists renounced earlier threats to ban tourism and alcohol, and decided against forcing women to wear headscarves. Following Iraq’s example, the Islamists also agreed to earmark parliamentary seats for women: half of seats in Tunisia, one-quarter in Egypt, and one-fifth in Morocco will be held by women.

What lay behind their electoral success? Islamists benefited from the complexity of voting patterns; they succeeded less because of popular religiosity and more because they could harness contradictory aspirations. Islamists reminded voters of their earlier resistance to argue that they were a new force that embodied a break with the past. But they could also present themselves as standing for ‘law and order’ and the only force capable of checking the spiral of violence — revealingly, Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood soon dissociated with the Tahrir Square protesters. In selectively endorsing modernizing economic and conservative social agendas, they might be compared to Europe’s post-war Christian democrats. Ultimately, however, their success was about their superior organization: during the years of fraught opposition, Islamist parties established infrastructures that could easily be turned to electoral campaigning, and they built credibility by providing services and welfare that despotic regimes were unable or unwilling to offer.

The Islamists now have a narrow window of opportunity. Whereas they could bask in ambiguity with slogans such as ‘Islam is the solution’ in the past, now they need to make hard political decisions and to sell their agenda. Islamic parties are required to keep campaign promises on jobs, services, rule of law, education, and social reform that will unlock hitherto suppressed potential. Failure to do so will mean that they go the way of the Muslim Brotherhood in Jordan: winning some 40% of the vote in 1989, their dismal performance in government meant defeat at the following election. If Islamists are not natural democrats, they will nevertheless be held to account by democratic processes — not just voters, but also other political parties.

For, far from winning power outright, the elections will lead to coalition governments in which the Islamists will be forced be broker compromises with nationalist and liberal secular parties. While they can emerge as the largest party, they will probably never secure a majority by themselves in any election – this is one possible reason for their reluctance to support a system that elects a head of state by universal suffrage and their preference for a new constitution aimed at creating a British-style democracy in which the parliament is the centre of power and the prime minister its executive arm in all but name. Turkey and Iraq provide possible models, but the Islamists movement is divided: in Egypt, the Muslim Brotherhood spawned four parties, and the Salafists three parties, not to mention other Islamist movements. All this means that no single Islamist party has much chance of monopolizing power in a way that would threaten pluralism.

If they have serious differences, what exactly do Islamists share? Many western commentators are quick to point to their shared social conservatism. But, if undeniable is so many cases, this is hardly their defining characteristic. On the one hand, some Islamists — take Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Prime Minister of Turkey — cannot be characterized in terms of their social conservatism; on the other, any country where religion has played a central role over the last half-century could be loosely characterized in these terms. It simply will not do to brand any Islam-tinted party as ‘anti-democratic’ and ‘anti-pluralist’ in a manner that would be wholly perverse if applied to Christian politicians in, say, modern U.S., Italian or Portuguese politics.

What really characterizes Islamists is their shared historical trajectory. Throughout the Arab world, their shared goal is to restore the centrality of an Islamic heritage that was marginalized during the colonial period. Around the turn of the century, the British and French empires undermined the nation building and evolution of constitutional politics that started during the first Arab Awakening. Pan-Arab nationalism filled the place of discredited democracy and provided a convenient vehicle for the insatiable greed of the new militarized elites. Their security states left the mosque the only space in which opponents could rally. Sites of worship proved stubborn bastions of the public sphere. If those who gathered in them only made social demands, over time they became increasingly political and even insisted upon forms of democracy. As the most popular and effective opposition, Islamists were also targeted by repressive regimes. Just as Catholicism in Poland played a pivotal role in the struggle against Soviet tyranny, a faith-based movement has proved equally effective against another form of despotism.

Skeptics will point to Iran’s 1979 revolution, broadly backed by democrats but hijacked by theocrats. But Turkey provides the more pertinent example for politicians and people alike. Turkey’s post-Islamist ruling party suggests Islamism can be synthesized into a pluralist secular order that avoids theocracy and sectarianism. While Erdogan is hardly secular by western European standards, he is nevertheless presenting the case for secularism as the best means to protect all faiths. Turkey’s experience engages Arab public opinion in a way that Iran’s does not: Ankara boasts not just democracy but a vibrant economy. Moreover, it shows that it is possible to modernize politics and the economy without sacrificing Islamic beliefs.

13113