The Washington Post

Story by Kevin Sieff

The route to Europe for many African migrants passes through the underworld of Agadez, Niger

The smuggler walked past the diaper aisle, through the back door of the convenience store and into the metal shed where the migrants were hiding.

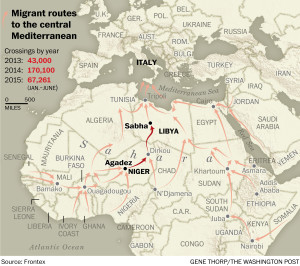

It was Monday in one of the world’s human-smuggling capitals, the day when trucks crammed with Africans roar off in a weekly convoy bound for Libya, the threshold to Europe. For Musa, an expert in sneaking people across the Sahara, it was time to get ready.

He walked around the white Toyota pickup parked next to the shed, loaded with jugs of water. Then he glanced at the cluster of 30 people waiting to climb atop the load.

One of them was an 11-year-old girl from Burkina Faso, sucking a lollipop. Another was a mother who held her wailing 6-month-old baby. Next to them, 27 men, from five countries, shifted their eyes nervously between Musa and the truck. If they weren’t caught or stranded or killed, it would take them three days to get from the stash house to Libya.

“We need to leave soon,” Musa said, examining the truck, its windows tinted, its license plate missing, prayer beads hanging from the rearview mirror.

Since the 15th century, Agadez has been one of the continent’s most important trading hubs, the gateway between West and North Africa. Now, it is a city run by human smugglers.

Across the developing world, migrants and refugees are leaving home in historic numbers. Increasingly, they are turning to smugglers, who load them onto flimsy ships or overcrowded trucks for treacherous journeys that kill thousands each year. Authorities in Europe and Asia have vowed to crack down on the multibillion-dollar industry. But the business of human cargo is thriving.

Musa, 38, knew the risks. He knew that if his truck broke down in the 120-degree heat, he and the migrants might survive no more than two days. He knew that his pistol was little help against the bandits who roamed the Sahara. But he also knew how to bribe the police and military to let him pass. And he knew the desert as well as anyone. Or he claimed to.

So this Monday, like every other Monday, he and his brothers counted the men and women who had arrived at the stash house tucked behind the gray storefront advertising soap and baby food. The sun had set. The migrants were covering their faces with scarves. Musa strolled past them in a long white robe, as if preparing for a leisurely drive.

He had permitted a Washington Post reporter and photographer to spend a week observing his operation – a rare window into the world of migrant smuggling. Like several others interviewed for this story, he spoke on the condition that his last name not be used.

“Before we had migrants, but not like now,” Musa said, standing next to his truck. “Now, there are so many that I can’t remember them all. Every week, the trucks are full.”

By 2013, at least 3,000 migrants traveled through the Agadez region heading north per week.

Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime

Outside of his mud-walled compound were dozens of other stash houses, which locals call ghettos. They were hidden behind homes, next to mosques and market stalls, part of the city’s secret geography, the architecture of a booming illicit economy.

It is a boom driven by the collapse of the Libyan government, which has left a vast stretch of North African coast virtually unguarded. But just as important has been Africa’s explosion of cellphones and social networks, which have linked smugglers to potential migrants.

“Now, in Sub-Saharan Africa, you’re never more than two conversations away from someone who can get you to Europe,” said Tuesday Reitano, a human trafficking expert at the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, a think tank.

Hundreds of men and women from across West and Central Africa pour into this desert outpost every week. The majority are fleeing abject poverty. Others are escaping violence in Mali, northeastern Nigeria or the Central African Republic.

Many have only one thing in common: They arrived in Agadez with Musa’s phone number.

Camel traders, merchants and livestock sellers gather at the local market in Agadez. The city, comprised mainly of one-story mud structures, is situated on the southern outskirts of the Sahara desert and has been an important trade center for centuries.

Konissa had stepped off the bus in Agadez the previous night, just after 11 o’clock. He had been traveling for three days from the Ivory Coast and his legs felt stiff and heavy. When he walked through the parking lot, men started approaching him, his small black backpack giving him away as a migrant.

“You going to Libya?” they asked in French and Hausa.

“You need some help?”

A smuggler from Agadez to Sabha, Libya costs between $150 and $300.

Washington Post reporting

But Konissa, 25, already had a contact in Agadez. His uncle had traveled to Libya last year.

“This man can help you,” the uncle wrote in a text in May, pasting in Musa’s number.

A few minutes after getting off the bus, Konissa dialed the number. The parking lot was full of young men sleeping on the ground. On the wall was graffiti in several languages.

“Ali from Cameroon was here,” one line read.

“A Guinean was here,” said another.

Konissa held the phone to his ear. He had spent two years saving for the trip to Europe, eking out a living as a tailor. If he made it to France or Italy, the money he sent back would change the lives of his parents and siblings and their children.

“Je suis arrivé,” he said to Musa. “I’m here.”

Fifteen minutes later, Konissa was driven to the large shed where Musa and his brothers kept the migrants. The ground was strewn with cardboard boxes and old tires. Five wild antelope, captured from the desert, skittered around the adjacent dirt yard.

Other migrants were sleeping next to a roaring yellow generator. The scene felt strange and scary. Konissa had never been this far from home. He lay down on the ground and used his bag as a pillow. He had brought a winter jacket, assuming it would be cold in the desert, but now, even after midnight, it was nearly 100 degrees.

He didn’t feel any closer to Europe, the place he had seen in the Facebook photos of his friends who had already migrated. They were always standing on pristine streets, or inside nice buildings.

“They always have the best clothes,” he said.

Before going to sleep, Konissa called his father in a village in the Ivory Coast.

“I found the place,” he said.

Western officials portray smugglers as hardened criminals who have driven the surge in migrants to European shores – where over 100,000 have arrived this year. The smugglers are “21st-century slave traders,” as Italy’s foreign minister, Paolo Gentiloni, put it. And indeed, there are alarming accounts of brutality by smugglers, including a recent Amnesty International report detailing how migrants crossing Libya faced rape, torture and abductions.

But in Agadez, smugglers see themselves as businessmen, providing a service that Niger’s desert tribes have mastered.

Musa’s father shuttled goods for years between Agadez and Libya, where U.S. and U.N. sanctions made legal trade difficult. By the time Musa was 20, he was crossing the Sahara, too. He learned to navigate by ruts in the sand during the day and by the stars at night. In 2011, Libyan leader Moammar Gaddafi was overthrown, and suddenly no one was stopping boats from leaving the country’s ports for Italy, just 200 miles away. Throngs of migrants began to arrive in Agadez. Musa was ready to profit.

He and his brothers bought a fleet of Toyota pickups stolen from Libya. They built the shed in the store’s back yard and laid down old mats and carpets where the migrants could sleep. They started taking between 25 and 100 migrants across the Sahara every week, charging about $300 each.

“My phone number became famous across West Africa,” he said.

In about three years, Musa was a millionaire. He bought homes in Niger and Libya. He bought cars and camels and smartphones, his selfies reflecting his swagger, a man lying next to a pistol in the desert. He married one woman in Niger and another in Libya. He tried to hide his enterprise from his four children, telling them that he was a trader. It was a rare glimmer of shame.

Countries around the world have vowed to fight the smugglers. The European Union recently announced a major operation to detain smuggling ships coming from Libya. But breaking up the networks is a colossal task.

“There’s so much money at stake that this has become almost impossible to stop,” said Mohammed Anacko, the president of the Agadez regional government council and the top official in the city.

Last month, a delegation from the European Union traveled to Agadez seeking to strengthen Niger’s law-enforcement agencies. Police and soldiers, however, are deeply involved in the trade. Many of them earn exponentially more in bribes from smugglers and migrants than they do from their salaries, according to a 2013 report from the Niger government’s anti-corruption agency, HALCIA.

Perhaps the most glaring sign of the complicity comes each Monday, when the smugglers and their migrant cargoes leave Agadez in a loose convoy led by a military escort.

“The diplomats come and talk about stopping migration, but it’s just talk,” Anacko said. “The smuggling networks are strong and the migrants are desperate.”

The Niger government has made sporadic attempts to shut down the smugglers. After the bodies of 92 migrants were found in the desert outside Agadez in 2013, officers raided a number of the city’s stash houses, arresting their owners. Musa was caught smuggling migrants and spent one month in jail. He resumed his business nearly immediately after being released, shifting his route to more remote stretches of desert.

Earlier this year, Niger’s government passed a law that would allow judges to sentence smugglers to prison for up to 30 years, but experts say it hasn’t yet been enforced.

Niger police take between $150 and $250 per truck in order to permit the illegal crossing into Libya.

Washington Post reporting

“If you pay the police, it’s no problem getting to Libya, even a truck full of migrants without papers,” said Maliki Amadou Hamadane, the head of the Agadez office for the International Organization for Migration, or IOM.

While the images of boats capsized in the Mediterranean have come to symbolize the dangers of illegal migration to Europe, the trip through the Sahara is no less risky. Last month, the bodies of 48 migrants were found in two locations a few hundred miles outside Agadez, according to the IOM.

Migrants fill up their water containers before they begin their trip to Libya. Each migrant carries two gallons of water for the three-day journey.

Musa shrugs off the risks of the journeys.

“If God writes that you will die in the desert, then that is how you will die,” he said.

He regularly stumbles upon the remains of those who didn’t make it, sometimes taking a shovel from his truck to dig graves.

“We bury the bodies because that’s what our religion tells us,” Musa said. “We do not say anything to the authorities.”

On this Monday afternoon, when the migrants staying with Musa went to purchase water containers for the three-day journey, most returned with one $2 gallon jug. It was all they could afford. They took turns filling them from a spigot.

Konissa carried a jug and a small loaf of bread. He had raced through the market to buy them.

“I am scared to be caught,” he said.

Migrants fill up their water containers before they begin their trip to Libya. Each migrant carries two gallons of water for the three-day journey.

Musa didn’t ask questions when the migrants arrived. When the 11-year-old girl from Burkina Faso named Saly showed up, wearing a long skirt with red birds on it, he looked at her but said nothing.

He knew, like other smugglers in Agadez, that not everyone he transported was choosing to make the journey. But he saw himself as a man providing a service. To a visitor, he emphasized his professionalism, pointing out that his truck had just been serviced and was unlikely to break down. He carried a satellite phone in case of emergency, unlike some of his competitors.

“They call me and ask for a trip to Libya, and I do it for them,” he said. “I don’t force them to travel anywhere.”

Just two days before Musa’s truck departed, a station wagon full of 12 Nigerian girls had entered Agadez, driven by a short, bald man named Jagondi, who even Musa described as a “big smuggler.”

The girls had been sold by their parents into a trafficking network, Jagondi said. It wasn’t an unusual event. He had been driving girls, mostly from Nigeria, on the route to Libya for years, taking extra care to hide his passengers.

“They will become prostitutes in Europe,” he said matter-of-factly, claiming that he is not involved in that part of the business, only the driving.

According to the United Nations, thousands of Nigerian girls and women have been trafficked to prostitution rings in Europe.

After dropping the girls at a stash house, Jagondi parked his station wagon in front of his own house, next to a large mosque. He sat outside and ate a bowl of rice and porridge. He recalled how, one night, he was driving around Agadez when he spotted a 14-year-old girl whom he had shuttled here. He remembered her fondly; she had called him “Daddy.” But that night, she was standing in a poorly lit back alley, working as a prostitute.

She saw him in the car and screamed “Daddy, Daddy,” he recounted. He kept driving.

“I was very, very sad,” he said.

For his part, Musa appeared less concerned about his human cargo. After he walked away from 11-year-old Saly, her uncle, who had accompanied her on the 1,000-mile journey from Burkina Faso, explained to a reporter that she had been sent by her parents to make money in Libya.

“She will wash clothes or do other work in the house,” said the uncle, Aziz Napon. “Back home, some women said ‘Don’t bring the girl,’ but she wants to have a job to help her parents.”

When she was asked why she was leaving home, Saly stared ahead and said nothing.

“She’s very quiet,” Napon said.

“Where is the little girl?” asked Musa’s brother Abdul Karim, standing next to the truck on Monday night.

Saly was sitting on a backpack on the ground. Three men lifted her onto the bed of the pickup, seven feet above the ground.

Then, one by one, the men climbed aboard. Musa and his brothers had stuck tree limbs between the bags and supplies so that the men sitting on the edge of the vehicle could hold on, their legs hanging just above the ground. It was the only way they could fit so many people.

“Do we need money to pay the police?” one migrant asked.

“Whatever I give you, they will take,” said a short, thin man named Mohammed, who works for Musa. “We will pay for everyone together.”

“Will there be bandits on the way?” asked another.

“You will be fine,” said Mohammed.

Konissa watched the others find their places on the truck.

“God willing, we will make it,” he said.

“Musa is the best. He’s a professional. He never loses the road,” Mohammed assured him.

Konissa’s uncle was living somewhere in Italy. The plan was to call him once the truck arrived in the Libyan city of Sabha, the next staging ground for migrants. Konissa already had the phone number of a smuggler there.

Musa had returned to his convenience store while the last migrants boarded the truck. He ate a quick dinner of porridge and goat under a shelf with board games and hairbrushes. Then he manned the cash register for a few minutes, selling milk and energy drinks. He emphasized his lack of concern.

“Sometimes I forget that we’re even leaving tonight,” he said.

Musa decided he would drive a separate truck this night, behind his brother, who would transport the migrants. Musa wanted to see his family in Libya and bring some supplies back.

When the first truck was full, two of Musa’s employees opened the metal gates that separated the stash house from a main road. The truck shot onto the street and past a mosque where women were praying outside.

“Libya!” one woman cheered.

The vehicle flew by the last mud-baked houses of Agadez and within minutes it was in the desert, in almost total darkness. When it drove into a ditch, the passengers groaned in unison, but everyone managed to keep their grip. The truck powered on toward the dunes ahead.

The only lights came from other trucks, also overcrowded with migrants, their faces covered in scarves to shield themselves from sand. Dozens of vehicles would depart for Libya in a single night.

After a few miles, the driver made room for Saly in the front seat, and the little girl was helped down from the load. Then the truck continued through the darkness, the Libyan border 350 miles ahead.

The next morning, the police in Agadez announced at a news conference that they had arrested about a dozen smugglers and 40 migrants.

Back at Musa’s store, his employees scanned photos of the detained. Neither Musa nor his brother was among them. Behind the counter, another of his brothers, Abdul Salam, laughed.

“Even when he was young, we called Musa ‘The Warrior,’ “ he said. “He wasn’t scared of anyone.”

Then Abdul Salam went back to work. The next migrants were due to arrive soon.

EXODUS | Desperate migrants, a broken system:

This is part of an occasional series examining the causes and impact of a global wave of migration driven by war, oppression and poverty.