Eurasiareview

by Christopher Ryan

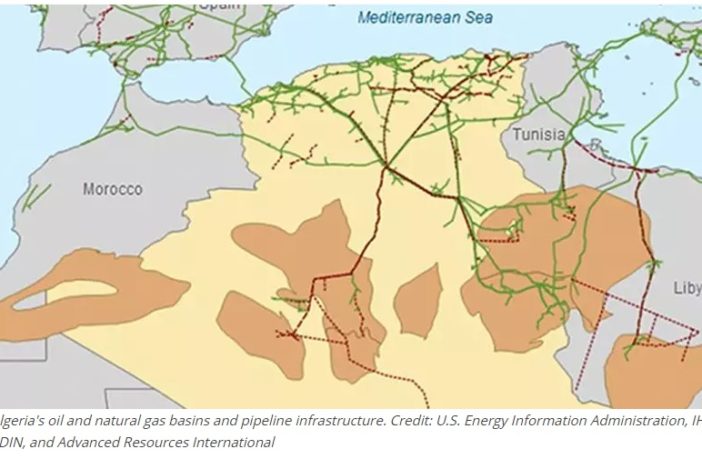

Algeria’s oil and natural gas basins and pipeline infrastructure. Credit: U.S. Energy Information Administration, IHS EDIN, and Advanced Resources International.

Algeria encapsulates frontiers that meet the Mediterranean to the north, while constituting a vast interior of Saharan Africa to the south. Algeria’s geographical features dictate its advantages as an exporter of oil and gas, and arguably its vulnerabilities as seen in the past, such as the Amenas gas plant crisis in January 2013 due to a terrorist attack carried out by an al-Qaeda-affiliated group that killed 40 people.

This paper discusses the various influences on Algeria’s export ability of its natural resources, and how it exports its energy to global markets while considering the extent to which the state’s security posture provides protection to those assets and their trade routes during a global crisis such as a pandemic. It includes an analysis of other 21st century disruptions like climate change, cultural and political inequality, and terrorism.

Algeria is located in North Africa and covers an area of nearly 3,000,000 square kilometres, where it borders the Saharan and Sub-Saharan desert nation-states of Mauritania, Mali, Niger, Libya, Tunisia, Western Sahara, Morocco: and The Mediterranean Sea to the north. It is the “largest country member” of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and Africa’s largest nation-state (OPEC). Its coastline meets Morocco to the west while reaching east to the Tunisian frontier.

The vast deserts of Algeria are a challenging feature for the transportation of its resources from remote locations spread throughout the Sahara. Pipelines run directly to shipping ports spread across the north of the country. The pipelines start at the centre of Algeria, Hassi Messaoud fields and extend to various international export terminals and refineries, before being shipped to Europe, the United States of America (USA) and South America, via the Mediterranean. Sea-lanes are a key strategic geographical feature for the export of Algeria’s oil and gas to the global marketplace.

Algeria has a nexus of continental and transcontinental pipelines that export its gas supplies across Africa and Europe. Algeria’s gas pipelines belong to the Algerian oil and Gas Company, Sonatrach, who, according to Morocco World News, are currently under investigation for selling “defective” oil to Lebanon. These allegations add to the “many corruption scandals” that have plagued the company since its founding in the 1960s.

Transcontinental pipelines are located throughout the Sahara Desert and connect to export terminals on the Mediterranean Sea. The pipelines run from “Hassi R’Mel to Arzew, Hassi R’Mel to Skikda, and Alrar to Hassi R’Mel” which exports to Europe (Sonatrach). The open sea between Algeria and Europe has had surprisingly little security issues during the construction and export of gas to Europe. This geographical feature is both a revenue and resource lifeline to Algeria and Europe; however, it remains vulnerable during a volatile global crisis.

Algeria’s three transcontinental pipelines export natural gas to Spain and Italy. There is the pipeline that crosses to Italy through the Trans-Mediterranean pipeline via Tunisia. The second pipeline goes through the Maghreb Europe Gas pipeline via Morocco, onto Spain. The third, is directly from Algeria to Spain, all via the Mediterranean Sea.

There are plans for two more pipelines that go direct to Italy, and the second directly through the Sahara, Sub-Sahara, onto Niger and Nigeria. There are security concerns for this operation due to the lawlessness of this region and the increased activities of militant groups. For example, al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and Boko Haram (B-H). However, recent studies by CTCSENTINEL argue “AQIM’s area of operations in Algeria has shrunk considerably and the group is constrained to areas south of Tizi Ouzou in the Kabylie region and possibly the Aurès Mountains in the east of the country. The areas’ geography poses significant counterterrorism problems.” Albeit random terrorist attacks have decreased in the last five years.

Oil and gas exports for Algeria reached record levels in 2011, just before the revolution swept across the Middle East and North Africa. Exports were around 52 000 000 000 m3 of gas by sea to Europe; the importing nations are Spain, Italy, Turkey, and France. These nations-states account for “96 per cent” of all exports from Algeria (Sonatrach). The remainder is bound for South America and North America.

Pumping petrol at the service station seems relatively simple; however, transporting it from the ground to the refinery and storing it is a complex process that occurs every minute of every day. Millions of barrels of oil and gas are moved through pipes, ships, trucks, and trains throughout the world, including the most volatile regions like North Africa. Algeria is one of these regions. The transportation of oil and gas has been at the forefront of security for the energy industry since its discovery. Also, the global terror threat has increased the vulnerability of the exploration and exportation of oil and gas, whether it be via sea lanes, and or via land.

The Strait of Gibraltar between Spain and Morocco is a vital sea lane for Algerian oil and gas tankers. In 2002, AQIM planned an attack on two large Algerian oil and gas tanker bound for the USA and South America. The Strait of Gibraltar is considered a critical choke point for global exports and imports. Keeping this strategic sea-lane safe is crucial to the global export and import markets and supply chains.

The Strait of Gibraltar choke point remains a contentious geographical feature because of various sea and land claims made by Spain, England, Morocco, and Algeria. It is yet to be seen how a multilateral defence operation would be played out by this group of littoral states if a terrorist attack on an oil and gas tanker were to occur. Thus far, there have been no security issues that have prevented the movement of the Algerian tankers in and out of The Mediterranean Sea via the Strait of Gibraltar. Although, threats are always present, and can disrupt the supply chain for export and import purposes.

Algeria has the second largest navy fleet in Africa, with the largest budget. Algeria’s Navy bases expand across the coast of Algeria. It has been successful in deterring any militant activity that may threaten the exit terminals for oil and gas. It would be difficult for AQIM to attack a tanker in this region as there are multilateral navy patrols from Spain, Morocco, England, and Algeria.

It remains to be seen if the impact of 21st century non-kinetic threats such as global warming, and now a pandemic like the coronavirus will have on the energy sector in Algeria. One thing is clear, oil prices have rapidly declined leaving countries like Algeria vulnerable to fragile domestic politics where they rely on energy revenue for state projects. While non-state actors like radical terrorist organisations within its borders and surrounding neighbours such as Libya and Tunisia remain a threat to Algeria’s national security, hence its energy sectors and supply chains remain even more vulnerable in an uncertain future.

In 1991, an election won by the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) did not go according to the Algerian military and the American government’s plan for Algeria’s post-colonial future. The military took control, and a civil war followed which pitted Arabs against Berbers, Muslims against non-Muslims, and Islamist fundamentalist against moderate Muslims. This was one of the most brutal civil wars in African history which resulted in over 200 000 people being slaughtered during the decade long conflict. The war ended in 2002, followed by a wave of terrorist activity which continues today in 2020. However, the Algerian security forces have prevented many attacks recently. There have been over 500 fatalities, including that of foreign oil and gas employees during this period.

Algeria is one of the most corrupt and inept regimes in the world that includes an appalling human rights record. According to the 2019 current Corruption Perceptions Index 2019, “Algeria is ranked at 109 in global corruption,” which is at the higher end of the corruption scale out of “180 countries.” A hangover government from the former President Abdelaziz Bouteflika regime supported by the powerful military still exist in 2020. There is little change in terms of infrastructure for health, education, and housing. Although, transport infrastructure has improved immensely across Algeria with urban metro-train lines now operating in the capital Algiers while national highways connect across the country.

Algeria consists of approximately 42,000,000 inhabitants of diverse ethno-political groups with a complex nexus of geopolitical state and non-state actors controlled by Arab Muslims and Indigenous Berbers. Challenges remain for the Algerian leaders in maintaining peace and stability in Algeria. With high youth unemployment and ethno-political tensions, Algeria remains volatile and unstable, both politically and socially. Algeria generates approximately 1/3 of all North Africa’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

In the last decade, there has been sporadic confrontations as well as riots between the Berber youth and the Algerian authorities. Demands for greater freedom, for example, include further recognition of the Berber culture and greater autonomy while protest have resulted in the deaths of protesting youth in the Tizi Ouzou province. This region is the Berber spiritual home.

The Muslim Arab Algeria transited from a French Algeria has achieved little to encourage solid foundations and good relations between Algeria’s Arabs and Algeria’s indigenous Berbers. It remains a tipping point for Algeria’s political stability. There has been little success by the government to create opportunities for the growing youth unemployment in Algeria. Oil and gas remain the dominant industry with no other major growth sectors apart from agriculture in existence.

Appeasing the youth of Algeria is a greater challenge to the security apparatus than that of climate change, pandemics (coronavirus) and terrorism, or the growing discord among the Berber population in the coming years. In the context of the coronavirus, The New York Times claims “Algeria has so far reported 5,891 confirmed infections, with 507 deaths and 2,841 recoveries” since the pandemic swept across the globe including North Africa. This will challenge Algeria’s health infrastructure while receiving support from China for testing and treatment of the virus during the global crisis. The loss of control by the Algerian authorities due to 21st century threats like a pandemic would create a scenario reminiscent of the civil war. The disruption to the global energy markets would be devastating in an already fragile global marketplace.

The relationship between Algeria and its neighbours has shifted since the Arab Spring in 2011. While broadcaster Aljazeera suggest the historical dispute over the Western Sahara with Morocco remains “tense” due to recent comments by a Moroccan diplomat naming Algeria as the “enemy” of Morocco. The borders between Morocco and Algeria remain closed while America has acted as an intermediary body during past regional discussions. There have been talks to discuss the reopening of the border, but little has been resolved to move forward. Opening the borders would economically transform the region for both Algeria and Morocco for all sectors, including the energy sector, and more importantly, the people of both countries.

The fall of the Libyan and Tunisian regimes in 2011 resulted in a shift for Algerian security on its eastern Saharan borders. It has been a relatively stable border region between Libya, Tunisia, and Algeria during the 20th century. But this is changing as governments remain unstable. It is particularly a concern for the energy sector as Tunisia is a transit point for the Trans-Mediterranean pipeline to Europe from Algeria. Both Tunisia and Libya have become a hotbed for armed Jihadist from around the globe since the removal of Libyan dictators Gaddafi and Ben Ali were forcibly removed from office during the Arab Springs.

Relations between Algeria and America have emerged reasonably strong since the end of the Algerian civil war. This is due to Algeria’s attempt to counter terrorism in Algeria, and the region in general. Algeria remains a key supplier of petroleum to the USA and gas to it European neighbours that include American investments. Algeria receives what the American congress calls “development aid” and assist in development throughout rural Algeria. It should be noted that Algeria purchases significant amounts of weaponry from the USA while Algeria benefits from American collaboration programmes.

The insurgent war in Mali in 2012/2013 created a new problem for the Algerian authorities. It encouraged a new stream of jihadist to the region, strengthened AQIM while old tensions re-emerged with France over its military involvement in the conflict close to Algeria’s borders. But the fact remains that a conflict on Algeria’s borders can occur and this is a concern to Algeria and the broader region in the coming decade while underscoring the threat to Algeria’s energy mix.

Terrorist militant groups operating in the Maghreb and Sahel are taking advantage of Algeria’s open and unpoliced deserts. These groups are enjoying a resurgence after the recent uprisings in Libya, Tunisia, and Mali: and are consolidating to become a powerful geopolitical threat. They are a menace to the oil and gas industry in Algeria and the broader region. Terrorist organisations ability to make an impact is evident by past events in Mali, Libya and the Amenas gas facility terrorist attack in 2013. The attack considered to be the most successfully orchestrated terrorist attack on an oil and gas plant in history was executed on the 16th of January 2013 in Amenas, Algeria. The terrorist siege lasted four days and resulted in the deaths of “40 oil and gas employees” (CTCSENTINAL).

Multinational oil and gas companies continue to express concerns to the Algerian authorities about security in remote locations around the Saharan Desert. Lives have been lost in the past while attacks can disrupt oil and gas supplies to the world which impact on global prices and the local Algerian economy. This would create a severe downturn and create further political and social problems in an already volatile region while being disastrous for Algeria’s stability, including disruptions to global resource energy markets and supply chains.

It is evident Algeria’s geographical features will continue to be a challenge to the energy industry in Algeria throughout the 21st century. Algeria faces many problems both nationally and regionally. Its incremental preparedness to engage with its neighbours and further afield will be an important step forward in emerging from a bloody and chaotic past.

Algeria has the ability and resources to meet the needs of its people and its global trading partners. It is time for Algeria to modernise and move forward, engage with its geopolitical rivals and allies to secure the future of its people and industries as it makes its way through the 21st century. Algeria must invest in the future of the nation and its people. History tells us that Algeria has survived decades of colonialism, civil war, terrorism and until now, avoided a 21st century revolution caused by an unprecedented global pandemic such as the coronavirus. How the Algerian government manages the impacts from the coronavirus will be critical to its peace and stability in the coming months and years, hence its energy sector.

*Christopher Ryan is an International Relations lecturer and researcher with a focus on post-conflict peacebuilding and development.

One thought on “Revising Algeria’s Vulnerable Oil And Gas Trade Routes During A Global Pandemic Crisis: Past Experiences – Analysis”

- Gerry DavisMay 21, 2020 at 6:41 amPermalinkThis is an excellent and thorough analysis of Algeria. I cannot believe the ‘Arab Springs’ did not disrupt the Algerian authorities as other MENA countries like Tunisia. Perhaps the coronavirus will.