Al Jazeera

Ali Aaouine had no job but one big dream; to start a rental car company in this town near the historic city of Fez.

In 2011, the 30-year-old joined a US-supported government programme called Moukawalati or “My Small Business”. This initiative was designed to help young Moroccans write business plans and get low interest loans.

Despite completing the programme and receiving a certificate, Aaouine couldn’t get a loan because of a lack of credit and assets. His project failed.

“They said they would supply loans, but they are just selling dreams to young people,” says Aaouine, who now works at a local association that helps young entrepreneurs.

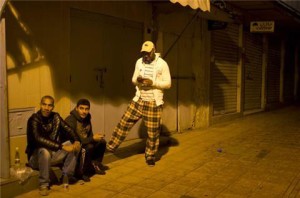

Throughout much of the Arab world, the rate of unemployed young people remains high, according to the World Bank.

Morocco, where one in three young adults is unemployed, is no exception. In this North African kingdom, which escaped the Arab Spring revolutions and is one the US’ staunchest allies in the so-called war against terror, there’s rising concern about the recruitment of young unemployed Moroccans into organisations like the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), which may provide a sense of purpose and even a regular stipend.

Every week in the capital Rabat, hundreds of young Moroccans stage protests demanding government jobs. Late last month in Marrakesh, at the first-in-Africa Global Entrepreneurship Summit, US Vice President Joseph Biden announced; “The opportunities for entrepreneurship have never been greater.”

“There’s much more to do, more young people to invest in, more to remove excessively cumbersome bureaucracies, more to embrace private enterprise,” he added.

In an effort to promote stability and combat youth unemployment, the US has injected $10m into Moukawalati to help young Moroccans start businesses.

Critics say the programme has fallen flat and the Obama administration’s emphasis on entrepreneurship to promote economic growth and stability is not an immediate fix in a country like Morocco.

Indeed, while the initial goal was 30,000 new businesses, Moukawalati sustained fewer than 4,000 enterprises nationwide. “All they give you is a certificate, and then you must depend on yourself to get a loan,” says Aaouine.

Moroccan Minister of Communications Mustapha el-Khalfi blames Moroccan banks for their reluctance to loan young people money. “There are many handicaps,” he said in an interview at the summit. “That’s why the programme didn’t work.”

Khalfi said one of the biggest problems in Morocco is a lack of a culture of entrepreneurship. For example, the education system focuses on rote learning rather than creativity.

Further, Moroccans resist taking financial risks for fear of failure, according to a recent World Bank report. In that report, 70 percent of young, would-be entrepreneurs named financial risk as the second largest barrier to starting their own businesses, right behind access to capital.

For many web-savvy Americans, crowd funding is another popular way to finance a start-up. It’s gaining ground in Morocco, but still a relatively new concept.

Last year, Lamiaa Bounahmidi, 29, founded LOOLY’s. The company aims to sell Moroccan-produced couscous to consumers worldwide. Bounahmidi was one of the first Moroccans to attempt raising funds through “Kickstarter” to finance product development and a road show in the US, England and Canada.

However, she only achieved a fifth of her goal, and 60 percent of that came from Americans.

“We had incredible support from all over the Arab region, but they didn’t pledge,” Bounahmidi said, attributing the low number of donations to a misunderstanding of crowd funding and low e-payment capabilities.

Circumventing bank loans altogether helped her get the business off the ground. She found initial financial support by entering, and winning, various international start-up competitions and has relied heavily on US-based incubators. When starting out four years ago, she says, Morocco had “nothing”.

Since then, organisations such as Centre for Entrepreneurship, Entrepreneurship Education and Development Morocco, and Injaz al-Maghrib, all supported by $1.6m from USAID have gained more traction, offering regular pitch competitions and empowerment conferences within Morocco.

However, not every young entrepreneur has access to these events, which mostly take place in cities.

Abderrahmane Bouhoute, 26, recently started a wedding planning company in his small town outside of Meknes. He rents the traditional dresses, caters the meals, provides the DJ and supplies the tent, which during wintertime is tied onto his parents’ roof.

However, as a college graduate who studied English literature, he didn’t have the training to start a company.

“It was difficult because I am not a businessman,” Bouhoute said.

Many believe that a lack of training, combined with a gap between what university students are taught and the skills companies need, are also handicaps for young entrepreneurs.

To address this, Aaouine, who never got his rental-car company off the ground, now runs Greenside Development, a US-funded organisation that gives in-depth business plan mentoring, funding and monthly follow-ups to young aspiring entrepreneurs – providing the support Aaouine feels he never received.

The organisation has helped launch 70 micro-enterprises since its start in 2011.

Morocco and the US, along with the governments of Algeria, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates, have committed over $31m over the next five years to the Stevens Initiative, a project named in honour of the late US ambassador to Libya, Christopher Stevens, who was killed in 2012 when fighters attacked the US consulate in Benghazi, Libya.

The programme’s pilot, aimed at promoting businesses, will launch in Morocco in 2015.

Additionally, the Millennium Challenge Corporation, a US-funded foreign aid agency, plans to finance at least $50m in “public-private partnership to provide vocational and technical training to equip young Moroccans with the skills they need to compete globally”.

Experts say entrepreneurship is not a cure-all for stabilising disenfranchised generations across many Arab countries.

“There’s no silver bullet,” says Jean Arlet, a World Bank analyst and coauthor of “Doing Business 2015.” “There are often a lot of things to do when tackling unemployment.”

Arlet says there needs to be an emphasis on building a smart regulatory framework before new businesses can thrive. For example, according to his report, Morocco does poorly with financial legal rights and collateral security – crucial for young start-ups with intangible assets.

While it’s clear entrepreneurship has challenges in Morocco, it’s clearly the government’s chosen catalyst for shifting dreams away from civil sector jobs.

“If you look in cafes, they are full of unemployed youth just sitting around,” says Bouhoute, owner of the wedding planning company. “The government cannot possibly provide jobs for all of them.”

Hannah Norman spent several months in Morocco on an SIT Study Abroad program and produced this story in association with Round Earth Media, a nonprofit organization that mentors the next generation of international journalists. Najwa Aboufikr contributed reporting.