Prominent salafists, modernists, human rights activists and security experts are all asking the same question: will Morocco follow Tunisia, Libya and Egypt to see a rise in radicalism?

Prominent salafists, modernists, human rights activists and security experts are all asking the same question: will Morocco follow Tunisia, Libya and Egypt to see a rise in radicalism?

According to a famed figure in Morocco’s takfirist movement, the state does not fear salafists as much as it fears the Salafi Jihadism movement.

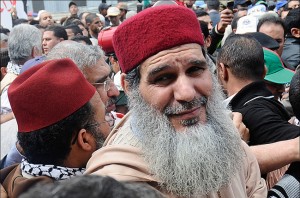

Cheikh Mohamed Fizazi received a 30-year prison term for inciting the perpetrators of the2003 Casablanca attacks before being freed under a royal pardon in 2011.

Fizazi, who was considered the leader of jihadist salafists in Morocco, started his career in 1976 as a preacher at a small mosque in Tangier. He soon formed links with jihadist movements in Algeria and Europe.

In an exclusive interview with Magharebia, Cheikh Fizazi explains that “Salafism in Morocco comes in different forms.”

“Once you exclude salafi jihadism – the one that is feared by the state because it adopts armed jihad – the rest does not represent a threat. Traditional Salafism is peaceful and relies on science and research and on expanding the role of the Qur’an,” Fizazi tells Magharebia.

He points out that salafist ideology in Morocco has seen a major shift in focus. Adherents began to engage in political activism, he says, such as involvement with the ruling moderate Islamist Justice and Development Party (PJD).

“Unfortunately, there is a naive definition in Morocco, where the salafi is the one who wears a short religious dress and a thick beard. This is wrong and superficial because even the king of this country wears a short dress and sometimes a beard. The salafi is someone who wants to live according to the path of the righteous ancestors by choice and conviction,” the cheikh says.

Moroccan salafists “were in the shadows, rarely in public”, Fizazi says. “They considered partisanship a bad innovation.”

“Yet when they decided to go out into the political arena, it became clear they were strong and surpassed even traditional parties in terms of discipline and seriousness. Their only problem is that they don’t follow one school of thought or one path,” the cheikh says.

“If they ever do that,” he adds, “they will upset the Moroccan political scene and turn it upside down.”

For his part, the leader of Traditional Salafism in Morocco, Cheikh Mohamed Ben Abderrahman al-Maghraoui, rejects any involvement in the political arena.

“The salafi movement is not a political party and cannot become one, because the foundation of salafi preaching is reform, call to God and to connect people to the Qur’an and the Path of the righteous ancestors,” Cheikh al-Maghraoui tells Magharebia.

The cheikh is best known for his underage marriage fatwa. The 2008 decree suggested marriage was permissible for girls as young as nine years of age.

“I am against converting the salafi movement to a political party,” the cheikh says. “Some want to establish a party, but if they consult with me, I’ll ask them: what are the components of this party, its prospects and its objectives? In my opinion, it is not possible to convert the idea of calling to God to a political party.”

“Salafi jihadism and salafi takfirism are political names,” he adds. “We of traditional salafism are innocent of these labels and practices…. We do not have agendas or political calculations. We do not favour violence and we believe that every Muslim has the right to live freely. We are with modernity, one that does not contradict Sharia.”

Amazigh rights activist Ahmed Assid is not worried about salafists in Morocco, saying there are too few to raise alarms.

“Salafists in Morocco are a small minority that does not threaten any of our gains. Salafists are located in Tangier, Marrakech and some suburbs of Casablanca and Rabat, but they are not forcibly large in other regions. Their weakness, politically speaking, is that they are scattered,” he says.

Assid has personal experience with the Moroccan salafists. In May, Assid unleashed a torrent of criticism, including a takfir fatwa, for suggesting that religious school textbooks lured youths to violence.

Cheik Fizazi said Assid should be sued for insulting the prophet, while Cheikh Hassan Kettani described him as a “criminal” and “enemy of God”, whose voice should be “silenced”.

“Despite all that, despite their considering us infidels,” Assid tells Magharebia, “we are not afraid of intimidation.”

“You cannot stop free thinking with any form of violence, either verbal or physical,” he concludes.

For Said Lakhal, a professor and researcher specialising in Islamic movements, the strength of Moroccan salafists lies not in their numbers but rather in their effectiveness and cohesion.

“In Tunisia, they are no more than ten thousand, but they imposed on the state to change laws,” he says. “Fortunately in Morocco, there is the authority of the king and the central authority of the state. Islamists in the government have a share of this power but do not have absolute power.”

“God forbid, if the regime collapses in Morocco, salafists will become more dangerous than their Tunisian counterparts. The reason is simple: they have previous terrorist experiences and a deep hatred of modernity,” the professor tells Magharebia.

Morocco could indeed become a hotbed of extremism, Lakhal says, and any leniency could allow salafists to control the street. Differences between salafist cheikhs are a mere formality, he adds, since they share one goal – to Islamisise the state and establish a caliphate.

“They are betting on the failure of the PJD to take advantage of the frustration and present themselves as the alternative saviour,” he says.

“They provided electoral support for the Justice and Development Party in exchange for political and judicial support, and for turning a blind eye to their activities. It is a game, that’s why the state should keep its eyes peeled,” the expert adds.

Mohamed Agdid, the former head of the Department of General Intelligence (RG) in Rabat, agrees that the intelligence agencies must be vigilant about the salafist movement in Morocco.

He is most concerned about Islamist group Al Adl wal Ihsan (Justice and Charity), but notes that it “lost some of its lustre and strength with the death of its mentor, Cheikh Abdul Salam Yassin”.

Still, civilians remain wary of the salafists.

Ben Diab Abdul Rahim, a French teacher in Meknes, says they “threaten the values of modernity and progress in the kingdom more than in Tunisia and Libya”.

“They espouse violence against those who disagree with their opinions and perceptions,” he says.

“Honestly, I predict a disaster if they are ever allowed to extend their dominance in the street and impose their paternalism on citizens,” the teacher adds.

Layla Amir, a 24-year-old student in the Faculty of Arts of Casablanca, tells Magharebia: “I am honestly scared of them. We have some in college. They are rigid and adopt violence and excommunication of those who disagree with them.”

“I have not forgotten what happened to that girl in Rabat last year, who was assaulted in the street by salafists because of her dress, which they considered tempting,” she says.

By Mohamed Saadouni in Casablanca for Magharebia