Is it useful to think of the Occupy movement more as a “left” movement or a “youth” movement? To answer that question, it’s worth looking into data on the young, particularly as it relates to unemployment.

To leave the United States for a minute, one way people are trying to understand the Arab Spring is through the lens of mass youth unemployment and inequality. Given how high unemployment has been in these MENA – Middle-East and North African – countries, what else could we expect besides revolution?

For instance, in early February then IMF chief Dominique Strauss-Kahn told a conference that ”this summer I made a speech in Morocco about the question of youth employment including Egypt, Tunisia, saying it is a kind of time bomb” and ”such a high level of unemployment, especially youth unemployment, and such a high level of inequality in the country create a social situation that may end in unrest.” Here is the “youth unemployment” blog tag at the IMF to give you a sense of what people there have been saying about it. In particular, they point out that it should be a major concern for the MENA and African regions.

Interestingly enough, there’s good research showing concern even before mass protests broke out. Regional IMF officials Ratna Sahay and Alan MacArthur gave a January 23rd presentation – Challenges for Egypt in the Post Crisis World – at the Egyptian Center for Economic Studies in Cairo (h/t WSJ). Protests would begin a few days later. Here’s a key slide from that presentation:

Part of you may want to immediately start getting your first-world privilege on. Maybe you are furious at terrible, unresponsive, corrupt governments ignoring the plights of their populations. Maybe you think that if these countries only had neoliberal, “flexible” wage contracts and a leakier safety net like we have in the United States then unemployment would be much better.

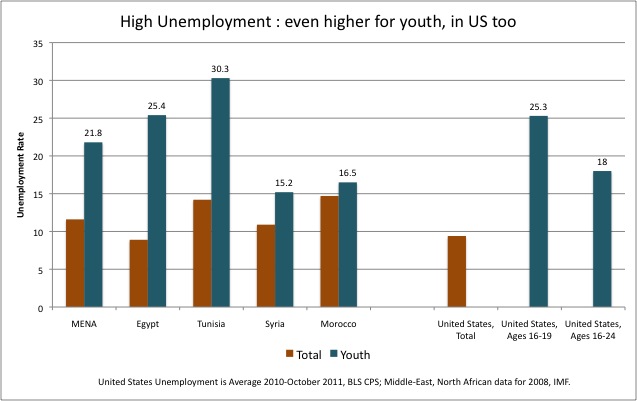

You may then head over to our monthly unemployment numbers and note that American youth unemployment is in the same ballpark as these MENA countries.

Let’s get some data going. I’ve taken numbers from the IMF presentation slide above, and compared them to United States youth unemployment averages from January 2010 to October 2011 from the BLS’ CPS data.

I can’t find what ages are used for youth for “youth unemployment” in the IMF’s definition, and I’m not even sure if it is consistent across the different countries they estimated. As such, I’m including ages 16-19 and ages 16-24, though I believe they are more likely looking at 16-24. For 16-19, we are at the same level of youth unemployment for Egypt and well above the region as a whole. At the broader 16-24 range, we are above Syria and Morocco, which both saw large-scale movement in the Arab Spring.

I can’t find what ages are used for youth for “youth unemployment” in the IMF’s definition, and I’m not even sure if it is consistent across the different countries they estimated. As such, I’m including ages 16-19 and ages 16-24, though I believe they are more likely looking at 16-24. For 16-19, we are at the same level of youth unemployment for Egypt and well above the region as a whole. At the broader 16-24 range, we are above Syria and Morocco, which both saw large-scale movement in the Arab Spring.

One potential explanation for the high level of youth unemployment in MENA countries is that they have huge demographic issues to deal with – they have a massive wave of people under 35 years of age to assimilate into their economics. What’s our excuse, other than confidence fairy terror spells and a desire to use the crisis as an excuse to go after public sector workers?

Also, given this, how could we have ever said youth unemployment in the United States’ Lesser Depression isn’t a “time-bomb”?

Bonus: I have to admit I’m a bit hardened to the various charts I’m able to put together from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ data, but this graph of the employment-to-population ratio for 16-24 year olds going back to 1948 floored me:

Remember the increase from the 1960s onward reflects women entering the labor force. And notice how it doesn’t improve after the early 2000s recession. Every age group has seen a substantial drop in the employment-population ratio during this Lesser Depression, but no other group I’ve seen comes close to this plummet. For the first time in half a century, a majority of young people aren’t working.

Remember the increase from the 1960s onward reflects women entering the labor force. And notice how it doesn’t improve after the early 2000s recession. Every age group has seen a substantial drop in the employment-population ratio during this Lesser Depression, but no other group I’ve seen comes close to this plummet. For the first time in half a century, a majority of young people aren’t working.