National Review

Benjamin Weinthal

Religion, economics, and demographics are a potentially explosive mix.

A remarkable series of barely noticed counter terrorism operations, labor strikes, and social protests in Algeria in January showed that the North African country may be facing a year of upheaval. Six years after leaders in the fellow North African states of Tunisia and Egypt were ousted, simmering instability in Algeria could lead to the ouster of its longtime president as well.

The consequences for the U.S. of a failed Algerian state must not be minimized. The U.S. State Department considers Algeria to be an important counterterrorism partner.

First, the military junta imposed a state of emergency on Algeria’s border with Tunisia upon the return of 800 Tunisian jihadists who had been fighting for jihadi groups abroad, including the Islamic State.

Second, cities in northwest Algeria and the coastal province of Bejaia experienced several days of labor unrest and riots. It began at the start of 2017, when the regime of President Abdelaziz Bouteflika, who is nearly 80 years old and has been largely incapacitated by a stroke, implemented a robust austerity plan, cutting spending by 14 percent and increasing taxes on consumer products. In response to the protests, Algeria’s security forces arrested about 100 people, half of whom were under 25.

The political and labor disorder has led the regime to call on religious leaders to quell the dissent. The Ministry of Religious Affairs has issued directives to imams to promote in their Friday sermons the maintenance of national stability as a religious duty. Prime Minister Abdelmalek Sellal warned that the regime will block any attempt aimed at “destabilizing” the country and asserted that the protests “are not related to the Arab Spring.”

Social unrest has also hit Algeria’s southern Saharan region because of a significant spike in electricity prices. In the February 1, 2016, issue of The Weekly Standard, John Schindler and I noted:

Together with the struggling Algerian economy, the fight to succeed Bouteflika may very well produce a series of increasingly public convulsions within Algeria’s formidable security and intelligence establishments, who are the country’s real rulers.

Our analysis has not changed. Indeed, the case is even stronger now, as the price of natural-gas and oil exports — the foundations of the nation’s economy — have not recovered enough to satisfy the demands of Algeria’s 40 million people.

To make matters worse, Algeria continues to squander significant resources on the so-called “Bouteflika mosque.” The $1.4 billion price tag on the mosque, with a capacity for 250,000 worshippers and the world’s tallest minaret, has diverted funds away from health care and social services. One purported rationale for building the Bouteflika mosque (or the Djamaa El Djazair mosque, as it is more properly known) is that it will serve to contain radical Islam. But that argument does not hold water in a country with 30,000 mosques.

The $1.4 billion price tag on the ‘Bouteflika mosque,’ with a capacity for 250,000 worshippers and the world’s tallest minaret, has diverted funds away from health care and social services.

Despite all its troubles, Algeria remains a key oil supplier to Europe and could help save energy-starved European countries from dependency on Putin’s Russia, not to mention the world’s leading state sponsor of terrorism, the Islamic Republic of Iran. Hence the U.S. has an important interest in maintaining a stable Algeria. Moreover, American oil and agricultural companies have recently secured deals with Algeria, and there is plenty of room for growth for U.S. companies in Algeria’s energy sector.

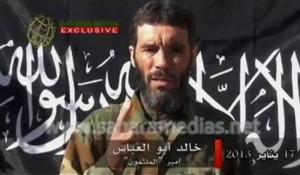

But the dangers of Algerian jihadism are alive and kicking. Mokhtar Belmokhtar — dubbed the “one-eyed sheik” after his injury in a botched explosion — is believed to still be active in Algeria. The U.S. has sought multiple times to liquidate him, but Belmokhtar — also known as “the Uncatchable” — has evaded all assassination attempts.

Belmokhtar, who named his son after Osama bin Laden, allegedly engineered the attack on the Tigantourine gas plant in eastern Algeria in January 2013. The terrorist assault resulted in the deaths of 40 oil workers, including three Americans.

Algeria’s formidable security apparatus has extensive institutional memory and experience in counterinsurgency warfare against jihadis. Between 1991 and 2002, at least 150,000 Algerians died in a civil war between Islamists and the military state. Most people who lived through the atrocities of this war have little appetite for another such conflict.

Youth employment hovers around 32 percent, and the younger generation’s readiness to effect change in stagnant Algeria could lead to a new revolt. The December 2016 U.N. Arab Human Development report examined Algeria and the age category 15 to 29. The Economist wrote in connection with this document: “Arabs make up just 5% of the world’s population, but they account for about half the world’s terrorism and refugees.”

Dire warnings have been issued about a pending implosion in Algeria and a flood of migrants to Europe. At least one prominent Algerian expert views this prediction as off the mark. Nonetheless, the dangerous mix of radical Islamism, economic instability, and growing youth unrest could be the recipe for a new Arab revolt in North Africa.

— Benjamin Weinthal is a research fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies. Follow him on Twitter @BenWeinthal