The Africa Report

By Benjamin Roger

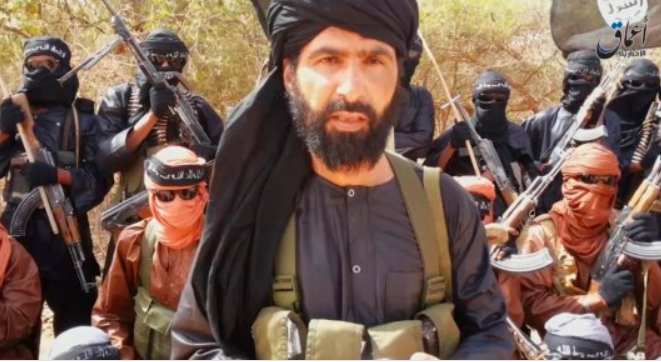

All the armies of the region are on his heels, as are the French, but the head of the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara remains elusive. A portrait of the most wanted jihadist in the sub-region.

Henry IV spent his life fighting wars. Some were won, others lost.

On 13 January, at the castle of Pau, where the King of France was born in 1553, Emmanuel Macron and his counterparts of the G5 Sahel know their war is far from over and that it will go through a merciless battle against their new “priority enemy”, the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (EIGS). His name was never mentioned, but in the wooded room decorated with medieval tapestries, everyone knew who was the target: Abu Walid al-Sahraoui.

Thousands of kilometres from the snowy peaks of the Pyrenees, the “Emir”, as he is called by his fighters, has for several years reigned over the tri-border area on the borders of Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger. Not a week goes by without an attack being reported. As in Indelimane, Mali, where 49 soldiers were killed on 1 November 2019. Or, more recently, in Inatès and Chinégodar, Niger, where 71 and 89 soldiers respectively lost their lives on 10 December and 9 January.

Religion as a refuge

Each time, dozens — or even hundreds — of assailants, on motorcycles or pick-ups, managed to hit their targets in a perfectly coordinated manner. After annihilating their opponents and seizing their weapons, they dissipate in small groups in the desert. They are elusive death squads, making their leader the most feared and sought-after jihadist in the region.

The sharp and often turbaned foreigner has been slow to build his infamous status. Born in February 1973 in Laayoune, Western Sahara, nothing predisposed him to lead this clandestine life so far from the family cradle.

His name is Lahbib Ould Abdi Ould Saïd Ould El Bachir, a member of the great Rguibat tribe. He grew up in Laâyoune before joining the refugee camps in Tindouf, Algeria, in 1992. There, he received a scholarship from the Polisario Front, passed his baccalaureate and then studied social sciences at the Mentouri University of Constantine, from which he graduated in 1997.

A year later, he began working in the Sahrawi Youth Union (also known as UJSARIO), where he was in charge of welcoming and accompanying foreign delegations passing through the Tindouf camps. The young Lahbib was then known for his generosity and dynamism.

However, in 2004, health problems affected him and he began to suffer from depression. Religion became his refuge. He became close to former Sahrawi students at the Ibn-Abbas Institute in Nouakchott, reputed to spread Wahhabism in West Africa. Radicalized, he joins the Islamist movement that was beginning to emerge in the refugee camps.

The Mujao thinker

November 2010, was his big start. He left Tindouf for the north of Mali via Mauritania, with a few other Sahrawis, and joined the Katiba Tarik Ibn Zyad, linked to Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (Aqmi). He soon noticed that no Sahelian was in command and that the chiefs were all Maghrebi — Algerian especially.

With the Malians Ahmed al-Tilemsi and Sultan Ould Bady, as well as the Mauritanian Hamada Ould Mohamed Kheirou, he founded the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa (Mujao) in the region of Gao in October 2011.

Abu Walid al-Sahraoui became its spokesman. Its stated objective: to form a Sahelian jihadist column with black fighters. On 21 October 2011, Mujao carried out its first major operation by kidnapping two Spanish humanitarians and an Italian woman in Tindouf. It is difficult not to see in this act the signs of the Sahrawi.

Then came the Tuareg rebellion in northern Mali and the coup d’état in Bamako. The country disintegrated into crisis. In March 2012, the jihadists of Aqmi and Mujao entered Gao with their black flags. Sahrawi became one of the masters of the city of Askia.

For nearly a year, with his bearded “brothers”, he imposed Sharia, made veils compulsory for women, enforced the cutting off of hands for thieves, and banned music, sport, alcohol, and tobacco. God’s fools dictate the law.

Unlike his “compatriot” Abdoul Hakim Sahrawi, another Mujao figure in charge of the city’s security, who often went around the concessions to stop at the coffee shops and chat with the inhabitants, Abu Walid al-Sahraoui remained almost invisible. Very few remember this quiet, discreet character, who was sometimes seen on the side of the hospital, a sort of governorate under the jihadist occupation.

Although he was little known to the inhabitants of Gao, many remark on his influence and ability to pull the strings behind the scenes.

“He was the intellectual of the gang, the thinking head of the Mujao,” said Mohamed Ould Mataly, now deputy of Bourem. Those who have attended meetings with him describe him as withdrawn, focused on his computer, speaking only for brief interventions — preferably in Arabic, even though he speaks French. And when he makes a decision, for example, authorizing certain humanitarian operations, he never goes back on it.

Of all the Katiba chiefs who controlled the city, he was the most radical. An ideologue convinced of the rightness of the religious struggle to which he devoted his life, he was in favour of a strict application of the Sharia. Mahmoud Dicko, the former president of the High Islamic Council of Mali (HCIM), who met him during a mission to Gao in 2012, remembers him as a “hard” and “uncompromising” man.

“He exuded a kind of self-importance. We did not agree at all and we left on very bad terms,” the Wahhabi imam said.

Break-up with Mokhtar Belmokhtar

Like the other Arabs of the Mujao, such as Ahmed al-Tilemsi or Omar Ould Hamaha, alias Redbeard, Sahrawi was close to Mokhtar Belmokhtar. The latter would later declare to a Gao personality that the Sahrawis are “his children” and that he “made them all”. In August 2013, after being driven out of the largest city in northern Mali by Operation Serval, the Mujao and the Katiba of Belmokhtar announced their merger to form a new group: Al-Mourabitoune.

Was this a form of opportunism, at a time when the Islamic State (IS) had erected its caliphate in Iraq and Syria? Or rather the death of Tilemsi, killed in December 2014 by French forces, which will give the turning point to Sahrawi’s journey?

A bit of both, no doubt. A few months later, in May 2015, he announced the creation of the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (EIGS), becoming the first Sahelian jihadist to pledge allegiance to the powerful organisation of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. The break with Mokhtar Belmokhtar was finalised.

According to various sources, the break had been simmering for several months. Some refer to disputes over the distribution of ransoms from hostage-taking. Others refer to profound doctrinal differences, with the Saharawi reproaching the Algerian for taking too soft a line in the application of Sharia law.

In any case, Abu Walid al-Sahraoui was now at the head of his own group. In the beginning, it did not carry much weight, perhaps a dozen Sahrawi fighters at the most. But among the various foreign jihadist leaders who scour the Sahel, he understood better than anyone else the need to establish himself locally in order to last.

He worked to establish ties with the people of Tabankort, where he was based, and relying on two influential Arabs in the region: Yoro Ould Daha, a former Mujao who has “recycled” himself into the Arab Movement of Azawad (MAA), and Hanoun Ould Ali, known as a local drug dealer.

“Yoro brought him fighters and Hanoun was his main financial supporter,” said one member of an armed group. Without them, Abu Walid would be nothing today. “For the two Malian Arabs, Sahrawi was, above all, a means of further consolidating their territorial control — and therefore their hold on various trafficking routes. With his seasoned men, he is also a strong reinforcement in the fighting between the Platform — of which the MAA is a part — and the Coordination of the Movements of Azawad (CMA) near Anéfis, in 2015.”

Local anchoring

At the end of 2016, the IS had lost ground on the Iraqi-Syrian front and acknowledged the allegiance of the ISGT (though this was only lip service). Abu Walid al-Sahraoui, however, gained legitimacy. Now based in the Ménaka area of Mali, he continued his local recruitment, mostly from a Peul, community that had been the victim of abuses and left out of the peace process.

Like some of his lieutenants, he married a Peule. Children were born from these marriages, which further strengthened the ties.

The EIGS was growing in strength. In May 2017, in Tessit, Abdoul Hakim Sahrawi, whose Katiba had rallied the Malian Gourma region, pledged his allegiance to him and recognized him as “Emir”.

A few months later, the EIGS achieved its first great coup. On 4 October 2017, its fighters ambushed a Niger patrol accompanied by American special forces in Tongo Tongo, Niger: five Nigerians and four Americans were killed.

The macabre video is a dazzling success on the IS propaganda networks. Sahrawi became one of the most prominent jihadist leaders on the continent. In Washington, where the death of the four soldiers was very badly received, a price of $5 million (4.58 million euro) was put on his head.

In the months that followed, EIGS launched attacks in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger. In the French, American, and Sahelian headquarters, Sahrawi joined the Malian Iyad Ag Ghaly at the top of the list of high-value targets — i.e. targets to be killed. Extensive efforts to neutralize him were to no avail. According to those tracking him, the man was a ghost.

Particularly vigilant, always armed, he is obsessed with his security and is aware of the material and human means deployed to flush him out. He never uses a telephone or makes any video or audio recordings. When he communicates, it is through handwritten letters. The vast majority of his fighters have never seen him. Only a small core of loyal followers, Sahrawis who have been with him from the beginning, can approach him. And when he has to move around, he does so on a motorbike, and without an escort so as not to attract attention.

“What gives him his strength is his local anchoring,” according to a Malian security source. “He is surrounded by people who know every cache for miles around. Even if all Western intelligence services start looking for him, it will be very difficult to find him.”

On the ground, the French forces behind Operation Barkhane understood that the fight would be long. Despite criticism, they cooperated with his Tuareg enemies of the Movement for the Salvation of the Azawad (MSA) and the Tuareg Imghad Self-Defence Group and Allies (Gatia).

At the end of February 2018, Sahrawis narrowly escaped a sweep operation south of Indelimane. According to three young fighters detained in Bamako who were then at his side, their leader was wounded in the fighting but managed to escape on foot. He then went to the Gourma, where he was taken in by Abdoul Hakim’s networks, before going to his family stronghold in the Tindouf area to recuperate.

This was a tactical withdrawal, during which the EIGS reduced its activity without losing its foothold in the region.

”During this period when he was weakened militarily, he had the security of betting on inter-community tensions to weld his troops around him,” said a notable in the Menaka region. During 2018, dozens of Tuareg and Fulani civilians were killed in massacres attributed to EIGS, MSA, and Gatia fighters.

IS, the “parent company”

Back in the region, Saharawi continued to grow stronger. In March 2019, his group is officially integrated into the Islamic State in West Africa (ISWAS), based in north-eastern Nigeria and better known by its English acronym, ISWAP. The former Polisario has proven itself in the eyes of the IS. This time, the recognition is frank: al-Sahraoui becomes the undisputed emir in the Sahel. The success was total. In addition to the visible rapprochement, the ISWAP would now stood to benefit from increased operational support from the “parent company”.

Several experts refer to the circulation of combatants and arms between the Tri-border area and the Lake Chad area via Niger. Foreign commanders have been sent to supervise the IMET combatants. This information was difficult to verify, but in recent months, Sahrawi’s firepower seems to have increased significantly. He can now count on several hundred fighters.

“The scale of the attacks, the way they are directed, the means used … These are no longer small ambushes with IEDs [improvised explosive devices] but large-scale operations that sometimes mobilize hundreds of fighters,” a security source in Bamako said.

The ISGT has money, and lots of it. In addition to the probable financial flows from IS in Libya and Nigeria, the group takes up the classic recipes of Sahelian jihadists: escorting, trafficking, ransoms, control of illegal gold panning across its vast territory, ranging from the Sahel reserve in Burkina to the Ansongo-Ménaka reserve in Mali, via north-west Niger.

Sahrawi also collects zakat (a religious obligation tax). Those who do not pay are threatened and sometimes executed. The same goes for all those who are considered opponents — including on ethnic grounds — or who are suspected of collaborating with the enemy. The strategy is simple: drive out the defence and security forces, scare away the administration, and empty the schools so that in the end the jihadists rule as sole masters.

Where will the 47-year-old jihadist stop? No one knows. But his strategic position, straddling three countries, gives him different tactical options. One day he strikes in Mali, another in Burkina Faso, a third in Niger.

Unlike groups linked to Al Qaeda, however, he has never yet claimed responsibility for a mass attack in a West African capital. The hypothesis that he is seeking to act is no longer dismissed and is, actually, feared by Western and Sahelian intelligence services. All the more reason for the heads of state and their staffs meeting in Pau to neutralise him quickly.

The response is being organised

As the French and Sahelian presidents announced in mid-January, the bulk of their military efforts will now be concentrated on the Tri-border area primarily to fight Abu Walid al-Sahraoui. The headquarters of the future Coalition for the Sahel is being set up at the French military base in Niamey.

For her part, Florence Parly, the French Minister of the Armies, announced at the beginning of February a reinforcement of 600 soldiers, most of whom will be deployed in the same area. Finally, once a funding solution has been found with N’Djamena, a battalion of about 600 Chadians will also be sent to the region.