New York Times

Lire en français

by Kamel Daoud

Who is still waging revolution in the Arab world? Not the Islamists, who have trapped themselves in violence or extremism. Not the left-wing elites, now aging, disarmed and discredited after the debacle of their nationalist movements. Not the young bloggers who were at the forefront of various uprisings of the Arab Spring: They are held back, sometimes frozen, by intimidation or censorship (throughout the region), police surveillance (in Algeria, Morocco and Saudi Arabia), prison (in Egypt) or death (in Syria).

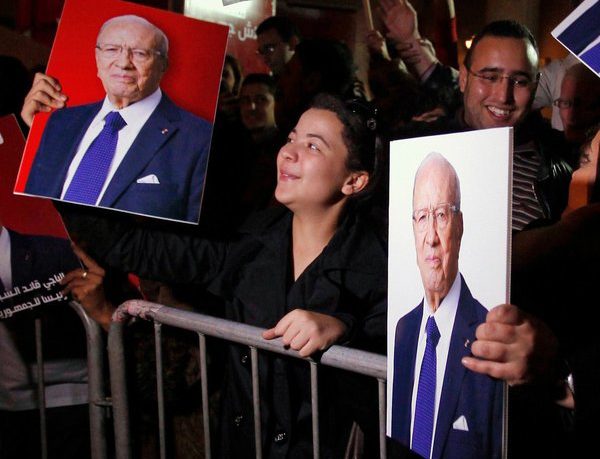

The only person who seems exempt from this harsh assessment is an elderly North African, a lawyer by training and a former militant in the anticolonialist movement: Béji Caïd Essebsi, the president of Tunisia. The good Arab revolutionary of the moment is a 90-year-old head of state.

If this statement sounds surprising, it’s because people in the West have yet to take the true measure of this man’s political finesse, including his ability to slowly consolidate a difficult consensus between democrats and Islamists. Tunisia admittedly is experiencing some problems, especially economic ones, as well as an intense controversy about a law — supported by Mr. Essebsi — that grants amnesty to former officials accused of corruption. But the president of Tunisia has also become the leading figure of reformism in the Arab world by advocating equal inheritance rights for Muslim women and their right to marry non-Muslim foreigners.

According to Islamic jurisprudence, barring exceptional circumstances, women heirs have a right to only half the inheritance of men. In Tunisia, and elsewhere in the Arab world, statelegal systems have not dared take on this taboo. Add to these rules a patriarchal structure that systematically dispossesses widows in favor of their brothers-in-law and parents-in-law. Together these practices undermine the independence of women, often reducing them to being dependents for life.

The constitutions of Tunisia, Algeria and other countries in the region may exalt freedom of conscience and of religious choice, but in Algeria, to take one example, a woman’s decision to marry a non-Muslim is still subject to ferociously dissuasive constraints. Her foreign husband must convert to Islam, in front of witnesses, and produce a certificate. Yet in the opposite case — when a Muslim Tunisian man wishes to marry a non-Muslim woman — nothing is required of the lucky lady.

These two sets of limitations have been in place in one form or another for centuries and constitute part of the ideological basis of Muslim society, which remains very rural overall. Virtually no political leader has dared challenge them for fear of losing popular support. (The reform project of Habib Bourguiba, the father of modern Tunisia and its first president, ran aground over fierce opposition from conservatives and zealots.)

Yet in August Mr. Essebsi delivered a speech before the Tunisian government that caused a storm. Even as he stated that he didn’t want to shock the Tunisian people, which is predominantly Muslim, he pointed out that under the Constitution, the Tunisian state was “civil,” and turning to the rights of men and women, added: “We must state that we are moving toward equality between them in every sphere. And the whole issue hinges on the matter of inheritance.”

In mid-September, another bombshell: At Mr. Essebsi’s urging, the government rescinded a 1973 administrative order forbidding Muslim women from marrying non-Muslims. Monia Ben Jémia, the president of l’Association tunisienne des femmes démocrates (The Tunisian Association of Women Democrats), underlined the measure’s significance for the entire Arab world. “Tunisia is becoming a kind of endogenous model of progress,” she said. “This calls out our neighbors in the Maghreb; it’s a very positive thing.”

Islamists of all stripes, well aware of the tremendous implications of Mr. Essebsi’s initiatives, were quick to react. An Egyptian preacher living in Turkey called the old Tunisian, “a criminal, miscreant, apostate and secularist.” In Cairo, the deputy of the Grand Imam of Al Azhar, the leading Sunni religious authority, declared on his Facebook page that equal inheritance rights “were harmful to women, unjust to them and contrary to Shariah law.” In Algeria, where I live, Islamist newspapers attacked Mr. Essebsi indirectly, echoing critical voices from elsewhere.

For its part, Tunisia’s main Islamist party, Ennahda, adopted an official position of reserve and silence — perhaps reasoning that open resistance would cast it in a bad light even as the country prepares for local elections in a few months. One could call the posture political, or politicking, but that doesn’t make it any less extraordinary: in fact, the reverse, because it privileges politics over ideology.

Mr. Essebsi’s declarations also have the virtue of highlighting what remains to be done in the Muslim world to complete the Arab Spring. It wasn’t enough to bring down dictatorships; now the patriarchy must be toppled. In addition to revising constitutions or imposing term limits for leaders, fundamental rights must be secured, and in practice, particularly those that ensure gender equality.

For the time being, laws throughout the Arab world tend to ratify inequality, especially when it comes to inheritance. In Algeria, despite the struggles of democrats and feminist groups since the country’s independence in 1962, the family code still largely tracks Shariah law: A woman’s choice of husband must be validated by a male guardian. So-called honor crimes — as punishment for adultery, among other things — remain widespread, even in countries deemed to be moderate, like Jordan.

The old Tunisian revolutionary has thus exposed one of the mechanisms that continues to handicap the Arab world: collusion between civil laws and religious laws. The latter overlap with the former and modify them, transforming their spirit, covertly or overtly. At the same time, Mr. Essebsi’s positions also suggest some means of resistance and possibilities for deep reform.

Is this the eve of another Arab Spring? Perhaps. Morocco, Jordan and Lebanon have finally abolished laws that allowed a woman’s rapist to escape prosecution by marrying her. Last week, the king of Saudi Arabia authorized Saudi women to drive cars.

But Saudi women, for example, are still not free to travel or dress as they please. And so it is Mr. Essebsi who has opened an enormous crack in the foundation of Muslim conservatism and set a unique precedent by validating various feminist and intellectual movements.

His stand has yet to be fully appreciated: It is revolutionary — Copernican, even. The president of Tunisia has proclaimed the equality of women in the Arab world, a social universe in which the Earth is still flat.

Kamel Daoud is the author of the novel “The Meursault Investigation.” This essay was translated by John Cullen from the French.