Dawn – by Zeenat Hisam

In achieving a balance between modernity and tradition, Morocco is coming to terms with the challenges of the time.

In June, we decided to explore Morocco’s enchanting cities and took a labyrinthine route into the country. From Casablanca, located at the central-western part, we traversed the northwestern cities of Rabat, Shafshawan and Tétouan. Finally, my daughter and I then came down to Fez in the central-north, proceeding to the southwestern city Marrakech, the last city on our two-week itinerary, before catching the return flight from Casablanca.

Sights and sounds of Rabat

As we got down from the train at the new Rabat-Agdal Railway Station, we marvelled at its state-of-the-art structure, facilities and ambiance. Opened in November 2018, along with the launch of the bullet train Al-Boraq, the station symbolises the transformation of the city into a dynamic modern metropolis, yet retaining some of its historic identity.

The first thing you notice as you get out of the station and your taxi cruises down the boulevards is the street art in Rabat, the capital city of Morocco. It is not the kind of the art on the walls you occasionally come across in a teeming metropolis like Karachi. In Rabat, you discover eclectic murals painted in vibrant colours not just on the walls but on the facades of commercial buildings, residential blocks, public institutions, car parks, letterboxes, or whatever adequate urban space is available. Painted in diverse styles — realistic, modern, calligraphic, digital, abstract, and surrealistic — street murals and frescoes take you by surprise and make you wonder at the spirit and the ingenuity of the city and, of course, the support of the state without which an art and culture friendly urban habitat is impossible to sustain.

I also discovered that local graffiti in Moroccan cities evolved gradually into a street art movement. The EAC L’Boulvart (Arts and Cultural Education), a not-for-profit association founded in 1999 in Casablanca, promotes contemporary music and urban culture in Morocco.

Since 2011, another association Alouane Baladi (colour of my country) involves the local population to embrace, and the artists to paint, the buildings’ facades on the themes of social justice, politics and feminism. The state supports such art projects. In 2013, EAC L’Boulvart began the annual street art festival Sbagha Bagha (‘paint desires’ in the Berber language) in Casablanca. Meanwhile, in Rabat, the National Museum Foundation supported the launch of its first street art festival called Jidar (wall) in 2015. The annual festivals, funded by the state and the corporate sector, invite local and international artists, identify spaces and provide materials.

Also read: When in Tunis, remember not to walk but stroll at a slow pace for pleasure

The taxi driver dropped us at the Derb Souaf gate of the medina, the old town in Rabat where we had booked a room in one of the riads which dot the old town. A riad (a garden in Arabic) is a house with a central open courtyard, an architecture we are familiar with in the subcontinent, though such havelis and mansions have been swept away under the forces of urbanisation.

“We have two types of traditional houses — riad and dar. The house with a fountain at the centre is riad and the house with a fountain installed by the wall is called dar,” the manager of the house told us. Many of the old dilapidated riads are bought by foreigners, then renovated and turned into guest houses. The riad we stayed in was owned by a Frenchman.

Rabat’s old medina was founded in the 12th century by Abd al-Momin as a fortress and called Ribat al-Fath (stronghold of victory). In the 16th century, Muslims expelled from Spain took refuge in the city. Listed as a World Heritage Site, Rabat’s medina has retained its organic character. Wandering in its narrow cobbled-stone and brick-laid streets, we looked at the many fascinating arched main doors, and wondered about the life stories unfolding inside.

An aspect that you notice in Morocco is the presence of women in public spaces. Well, definitely more noticeable than women are on the streets and public places in Pakistan. Morocco is still a traditional Muslim society when it comes to women, though women are breaking barriers and the state policies and laws are supportive of women’s empowerment.

As a traveller, you come across women running small businesses. You find a greater number of women in services and administration. The hotel industry has its fair share of female employment but in the lower tier, as is the global trend. In all the riads we stayed in, there were women housekeepers, cleaners and sometimes managers. Fawda, a petite, agile woman of 41, manages the 8-room riad, takes care of day-to-day operations, including reservations, food services and allocation of housekeeping tasks to the all-female cleaning staff. “I am working here for the last three years,” she told me in broken English as we chatted for a while. Fawda holds a Baccalauréat Technique diploma (15 years of education) and had earlier worked at a printing press.

The first place we were keen to visit in Rabat was the Kasbah des Oudaia and the Andalusian Gardens. Fawda told us to take a stroll down the alleys of the medina which opens at the northern end to Kasbah des Oudaia and the Gardens. Rabat’s old walled city, or Madina, was the first in Morroco that we had the experience to explore. Rue Souiqa is the main market street. On the western side are the shops catering to local residents and its eastern streets branching off from Souq-al-Sebbat sell exotic arts and crafts and merchandise to tourists. Many of the streets are wide and have been recently renovated with beautifully carved wooden covering under the Old City Rehabilitation plan.

Kasbah des Oudaia, located on a hilltop at the mouth of river Bou Regreg and the Atlantic Ocean, is a fortress. Built in 1150 AD, it holds a palace (now a museum), an old mosque, a residential quarter and the Andalusian Gardens which were added later. The massive door, Bab-i-Oudaia, was half opened and when we tried to enter, we were told the museum was closed for renovation. We then walked down the adjacent carved sandstone arched door leading to the kasbah’s narrow, cobble-stone winding alleys. Houses were painted white with blue skirting and the doors were colourful, each with a distinct character. Some of the alleys had curbs where artisans displayed their wares: zillij tiles, ceramics, wooden and leather crafts and rugs.

One of the alleys, Rue Bazo, leads to the enchanting Café Maure. Located at an elevation and spread over several terraces, this open-air rustic café has sandstone columns, tiled walls, blue and black wooden stools and tables, and grassy platforms to sit on. The café offers only mint tea and coffee. Cookies and pastries are served separately by men who let you choose from a large round tasht that they carry around. There were more Rabatis than tourists at the café and one of them was playing a ney (flute). We slowly sipped the hot fragrant mint tea, inhaling the serenity and the charm of the place and looked down the terrace at the Bou Regreg river that separates the city of Rabat with its ancient sister-town Salé.

The visit to Kasbah des Oudaia is not complete without a sojourn to the alluring Andalusian Gardens. Though smaller in size, compared to the historic gardens in the Subcontinent, i.e. Shalimar Garden Lahore, Andalusian Gardens take your breath away as you enter. They have an exquisite layout with arches, structures and fountains but a friendly, cosy atmosphere. You can sit on benches under the shady trees, admire the fruit trees — orange, lemon and banana — look at blooming bougainvillaea, the foliage and flowers, relax, and watch children and kittens playing and cats napping. We had not come across so many cats at one place yet in Morocco. We wanted to linger on but the Gardens close early at 6 p.m. and we were reluctantly nudged to the entrance when the guards whistled at us to exit.

The next day Fawda arranged a taxi for us and we set out to explore the city. The first landmark was the famous Hassan Tower, an incomplete minaret of an ancient mosque whose main hall was built but whose construction was halted in 1199. The mosque was destroyed in the massive earthquake of 1755. Remnants of the wall and the tower, both made of red sandstone, and 348 stone columns of varying heights, overlooking Bou Regreg river, gives the site an eerie feeling. Opposite Hassan Tower, stands a grand structure on a raised platform — Mausoleum of Mohammad V — completed in 1971. Made of marble, intricate zellij mosaic tiles and carved cedar ceiling, it is an impressive blend of traditional and modern Moroccan architecture. Adjacent to it is a sandstone mosque built in traditional style which completes the site. What I found missing was the plaque or the information slab which are usually found at historical sites.

More on this: The spices and flavours of Marrakech will tickle your tastebuds

One of the features that I liked most about Rabat is the blend of traditional architectural elements with a modern use of interior space that many of its official buildings exhibit. The Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, opened in 2014, is one such example. The outermost façade of the Museum is a white colonnade of double arches with latticework. Inside the arches is the chromatic façade displaying large reproductions of works or artistic announcements of exhibitions and events. A huge mural, Time for Africa, which showed a woman painting with vibrant colours the motifs of Africa as a child looks on, welcomed us as we entered the Museum which holds a permanent collection of Moroccan artists and curates local and international artworks. We wandered in several halls, had coffee in its café and bought an artist’s watercolour rendering of Rabat’s various sites in a handy book form.

We asked the taxi driver to take us to La Marina, located at the mouth of river Bou Regreg, on the shore of Salé, an old city which served as a haven for pirates in the 17th century. Before Morocco’s independence, Salé was a hotbed of nationalist movement. The city of Salé is connected with Rabat through a new bridge and the Rabat-Salé Tramway. At La Marina, many luxury yachts and sailboats were docked. Though the Marina complex was gated, our taxi was not stopped. While strolling down the promenade, lined with cafés, boutiques and modern luxury apartments, we spotted many local people enjoying the site and the sea, sitting on the benches.

In the evening, we looked forward to meeting Salma, a young Moroccan Berber woman living in Rabat, whose contact was given to us by Zoya, my daughter’s friend. Salma invited us for dinner at Zayyane restaurant located in an upscale area. Avenue Annakhil is one of the many splendid boulevards of the area with an impressive roundabout. The restaurant, facing the square, spills over to a sidewalk with a beautifully arched façade with delicate latticework, reminding us of a jharoka. We sat outside and took a good view of the surroundings.

Salma, dressed casually in a striped t-shirt and jeans, wearing a gold pendant, shaped as a tiny map of the subcontinent, turned out to be an amazing woman with a fairy tale kind of a personal story. Salma’s family comes from Atlas, the mountain range in the southwest of the country that stretches through Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia. Her parents moved to Rabat when she was a child. Salma, a graduate from Rabat University, went to work and live in Casablanca on her own for a few years. Since her return to Rabat, she has been working as an HR manager in a company. While reflecting on her interest with the subcontinent’s culture, history, music, fine arts, she told us she fell in love with the region at an early age through watching Indian movies and Pakistani TV dramas. This fascination led her to study various aspects of South Asia on her own. It was Pakistan that won her heart eventually, firstly due to religious affinity, and secondly through a romantic friendship. While in high school, 17-year-old Salma met and befriended a boy from Lahore through a youth-run organisation. Now after 10 years of internet contact and three visits to Pakistan, Salma is set to marry her soul mate in November this year in Lahore. (Postscript: Salma got married in November 2019).

Fluent in several languages — mother tongue Amazigh, Darija (Moroccan Arabic), standard Arabic, French and English, Urdu and Hindi — Salma profiles herself on social media as a person ‘Lost somewhere between India and Pakistan. Accidentally born in Morocco’. She joined a social media group of young Pakistani booklovers, Bookay, in 2013 and since then has made a lot more friends in the subcontinent. Aside from her unusual love for the subcontinent, Salma represents the young urban Moroccan woman — aspiring for higher education, economic participation and freedom to choose her own path in life.

Chefchauoen, the ‘Blue Pearl’ of Morocco

As our bus moved away from Rabat, traversing the plains and the slopes, and then wound its way up the Rif mountains, I looked at the view: scenic, yes, but those who have seen the Himalayan and Karakoram ranges and its many valleys, the Rif mountainous region has nothing to write home about. But when the contours of the ‘Blue Pearl’ of Morocco started to emerge, I couldn’t take my eyes off the window of the moving bus. Nestled up on the mountain terrace, the city looked enticing in its many shades of blues and neat structures. Spelt Chefchauoen, a word I had wondered about and was not able to pronounce properly, turned out to be شفشاون on a signboard in Arabic — simple and melodious.

The bus dropped us at the station located at the slope of the valley amidst the sleepy city’s administration buildings and new residential areas. We took a taxi to get to the medina, the walled city founded more than six centuries ago and got down at the main square. That Friday, the square, lined with small cafés and shops, was bustling with activity as the weekly vegetable market set up at the centre was in full swing. We waited for the person from Dar Meziana, the guest house we had booked in, to fetch us.

A young man came to guide the way and we entered the old stone arch Bab el Ain. Inside the arched door, a labyrinthine network of narrow alleyways spiralled up, lined on both sides by blue doors and walls. One of the alleys with stairs painted blue led us to Der Meziana. Inside the patio of the hotel, very fine paintings —street scenes from Shafshawan — and decorative tiles with silhouettes of Moroccan men in jellaba and women in kaftan painted in pastel shades adorned the walls, all signed by the same artist. The young man at the desk told me the artist is a friend of the owner. When asked if the tiles were available for purchase, he showed me several reproductions for sale and I bought three.

We got up at the break of dawn on the echo of the azaan. From the balcony, the city appeared peaceful and quiet, with its many shades of blue gleaming in the golden morning rays. After the sumptuous breakfast at the terrace of the guest house, we set out to explore the medina. The main street had small shops on both sides, full of exquisite handicrafts — woollen, leather, wood and ceramics, and paintings by local artists.

Dotted by tea shops and dhabas, the street was coming alive, with shops opening and sellers arranging their ware and crafts on bamboo baskets. The pace was relaxed. The alleys shooting out from the main streets had potted plants and at several places, doors were covered with grapevines, bougainvillaea and other creepers. At vantage locations, signboards of riads and spas peeped out from the foliage.

Read further: The old ‘modern’ neighbourhoods of Istanbul

Most of the shops and galleries in the old medina are owned and run by the families of local artisans and artists themselves. In Morocco, I observed that artisans and craftsmen, working under many cooperatives, are respected and valued for their skills by society and supported by the state through exhibitions (i.e. Artisan Expo), trade shows and linkages to international artists and experts in the field. The younger generation, that receives 12 or 14 years of schooling, often take to the family craft and trade.

Ayub, a young man of 23 who manages a small gallery, tells us he comes from a family of painters. His elder brother, Ismail, and his cousin Yousuf — whose signatures we noted on the many canvases — paint scenes, mostly in oil colours, from Shafshawan. Both have studied up to baccalaureate level. They say, “Most of us love to draw and paint. We learn it from our parents. Shafshawan city does not have an art school. But nearby at Tetuoan, we have a fine arts school’.”

Another shop full of painted ceramics and tiles, canvases, local objects d’art and hand-made jewellery is owned and run by a soft-spoken 38-year-old Mohammad Ouragli, who paints with a unique medium — sand mixed with colours. Ouragli tells us he is from Andalusia. Shafshawan, founded in 1471 by Abu al-Hassan Ali ibn Moussa ibn Rashid al-Alami as a small fortress to fight off the Portuguese invasion of northern Morocco, provided refuge to Muslims and Jews fleeing from Andalusia, Spain. Until today, many of the residents feel proud of their roots.

Shafshawan was full of tourists — mostly Europeans, Americans and Japanese — strolling the alleys, taking pictures. We came to know that the city has some Chinese residents as well: we spotted signboards of Chinese food and visited one of their dhabas.

With minimum, basic furniture, this small place is managed by Tin, a 30-year-old Chinese woman, and her two friends. The food was good, prepared by a Chinese chef.

During a chat, Tin told us she and her friends come from Hunan. A few years back she, a school teacher, and her male friends visited Shafshawan and fell in love with the place. They decided for a longer stay, invested some money, rented a place and started the eatery, catering to the few Chinese families residing in the city and tourists.

“I like it here. The pace is slow, not like in China, which is so frenzied, just work, work, work. We now shuttle between Hunan and Shafshawan. We plan to try out this mode of living for three years.”

We were told that the residents paint their houses and alleys twice a year with a mixture of chalk, pigment and water. I wondered if it was a sense of collective identity and collective good that all agree on one colour or was it due to a royal decree? It was difficult for me to find the answer from locals due to the language barrier. Whatever the answer, a traveller in Morocco gets the impression that each city has developed its own distinct identity and the inhabitants are proud of it. Apparently this has come about through an urban planning process which involves rehabilitation and sustenance of historic sites, creation and maintenance of public spaces, consultation and consensus of residents, respect of traditional culture and its blending with modernity and enriching with state-of-the-art techniques.

Tétouan, city of artisans

The next day we decided to visit the nearby city Tétouan. I was keen to visit Tétouan as I was told by several shop keepers in Shafshawan that Tétouan is known as a city of artisans and artists and many art galleries and craft shops in Shafshawan are owned by Tétouanis. Also, the city has the only fine arts university in Morocco, the National Institute of Fine Arts Tétouan. Unfortunately, it was closed the day we visited. We took pictures of students’ art projects placed in the verandah and the garden.

Tétouan was an hour drive away from Shafshawan. We drove past several fruit orchards — orange, lemon, pomegranate, almond — in the valley. On the northern slopes, at the foothills of Jabal Dersa, lay الحمامتہ البیضاء or ‘white dove’ as Tétouan is nicknamed by the Moroccans. The taxi driver dropped us at the plaza, outside the walled city.

Magnificent in its layout, the square has patterned tiled floor — brick-red, emerald green and white. At the centre of the vast courtyard was a three-arched gazebo, with a slanting green-tiled roof. There were stone benches, lamp posts, and palm trees. On the left was Café Granada, a structure in white and green with arches, verandas and a central garden. We sat on the veranda and had a snack and tea. Though the old wall of the medina is in mud colour, it blends beautifully with white abodes inside. At the far end of the medina, at the top of Jabal Dersa, are the ruins of a historic garrison.

Tétouan’s medina, one of the seven historic cities of Morocco on the World Heritage List, has some of its main streets, or souks, covered with wooden crisscross jali. At several places, we noted plaques, placed for the Unesco World Heritage sites, such as one at a pastry shop indicating the original name, al-Ayoun Oven, built in the 17th century. The alleys leading to residential areas are narrower and have retained old stone arches. The new city, outside the medina, has wide streets, boulevards, modern buildings and beautiful squares. One roundabout had a large white dove at the centre, surrounded by national flags. Moroccan cities are adorned with national flags at too many places. Red flags with a green star at the centre pop up every now and then. Is it really needed? I wondered. Do fluttering national flags imbue the people with love of country? Or does love and faith in one’s country spring from one’s heart without any external trappings?

Exploring history in Fez

After a six-hour journey from Shahfshawan, we got down at the bus station in Fez, the highlight of our journey, wherein lies the oldest Islamic metropolis, that has retained its character and structure through the centuries.

We took a taxi to reach Riad al-Tayyur, or ‘House of Birds’, in Fez al-Bali, the old medina. At the small square outside Derb al-Miter, one of the many entrances to the medina, a man from the guesthouse was waiting to guide us through the alleyway.

When we entered the tall arched main door of the guesthouse, stepped into the vestibule and came to the central open courtyard of the guesthouse, an alluring inner garden awaited us. At the centre of the beautifully tiled quadrangle space, lay a marble fountain inside an octagonal basin decorated with intricately patterned tilework, surrounded by four earth patches, each with a tall fruit tree at the centre ringed by herbs, plants and foliage. The verandas on four sides had seating and dining arrangements. On the main veranda were inscribed in calligraphy verses about the birds Simurgh from Shahnama and Hudhud from the Holy Quran. Underneath was a beautiful cage with a white dove perched on a delicate swing. On each veranda a tall, exquisitely painted, carved wooden door panels opened to an arched stained-glass door leading to a finely furnished guest room.

The courtyard echoed with the chirping of different birds. The manager told us the owner, a Frenchman, loves birds. On the first floor, the colonnade balcony had several more bird cages.

We had reached in the evening and came to know that Riad al Tayyur did not serve dinner. The manager recommended another guesthouse and a young man guided us through the labyrinthine alleyways. After a long tiring walk for me, we reached Der Attajalli, another guest house, this one was owned by a German woman who bought the place in 2006, renovated it and opened it as a guesthouse in 2008. “In those days, not many riads were turned in to guest houses,” the young manager told us.

Riads, or stately mansions, once owned by rich merchants and elite of the medina fell into ruin with the development of new residential areas outside the historic neighbourhood. In the 1960s and 1970s, local and foreign artists and writers bought and renovated these architectural gems to use as personal retreats. In the 1990s, with state policies promoting tourism and foreign investment, Europeans, especially the Spanish and the French, started buying property. “And now we have many riads owned and run by foreigners as guesthouses,” he said.

After we had a delicious tagine, another young man guided us back to Riad al Tayyur. A caring person who seemed to have all the time in the world picked up a plastic chair from a nearby kiosk and made me sit to catch my breath intermittently at suitable spots in the winding alleys. Later, I would read what Rachid Moumni, a contemporary poet from Fez, has to say about these alleyways:What hidden melodiesNearly awaken the twisting lanes,the doors,and the slumbering roofswhat effects will be written on the earthen stairsswept cleanwith a broom of light?

The medina of Fez has more than 9,000 alleyways and it is said unless a local guides you, you would be lost in the labyrinth. I would say you can negotiate the maze with Google maps: you need a local sim with a speedy wi-fi and a lot of patience because at times you may go bonkers with Google’s confusing direction for turns left and right. My daughter managed with her smartphone to find our way to the sprawling alleys and back to the guesthouse. But for a visit to the oldest and continually functioning university, Al Qarawiyyin, and the historic Madarsa al-Attarine and Madarsa Bou Inania, located inside the medina we sought the help of a guide.

The guide showed us the way to Derb Boutouil, a wide street inside the old quarter, where the main door of the Al- Qarawiyyin is located. When we entered the tall, wide, ancient brass door of the historic complex, a simple yet majestic structure of white columns and arches, green-tiled pyramidal roof, a quadrangle minaret and an open courtyard with a fountain at the centre lay before our eyes. I felt ashamed of my ignorance: I did not know that the first-degree awarding institution of higher education in the world was founded by a Muslim woman, Fatima al-Fihri, daughter of a wealthy merchant who migrated from Qarawan, Tunisia, and settled in Morocco.

The Al Qarawiyyin complex comprising a madrassa, a mosque, and a library was established by her in 859 CE in the city of Fez. The list of alumni of this school includes historian Ibn Khaldun, geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi, philosophers Ibn-e-Rushd and Abu Imran Musa. The institution was expanded over the centuries by different Muslim rulers.

In 1947, Al-Qawariyyin was integrated into the state educational system and in 1963 as a university and the campus shifted to another building outside the medina. Besides Fez, Jami’a Al-Qarawiyyine has a faculty each in Marrakech, Tétouan and Agadir. The library which is part of the complex in Fez, with a collection of 30,000 old manuscripts, including one of the oldest copies of the Holy Quran in the world, is not open to the public. We sat for some time in the women’s prayer gallery of the Al-Qarawiyyine mosque. There were many old women in abaya and kaftan with tasbih in their hands. Children played at and men performed ablution at the fountain.

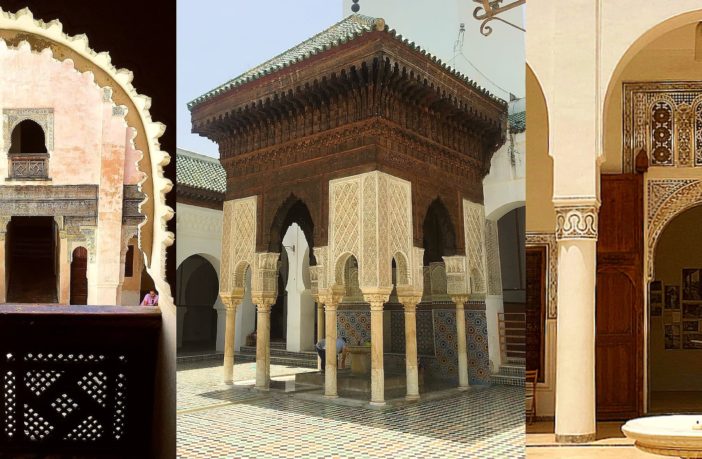

The guide, who was waiting outside, led us to Madarsa al-Attarine, named for its location at the entrance of the spice and perfume market, Souk al-Attarine. Built in 1325, as an annexe for nearby Al-Qawariyyin, by Sultan Abu Sa’id Usman II, the Madarsa al-Attarine has a rectangular courtyard that opens to a prayer hall lined by small rooms which once served as students’ accommodation. It was calm and peaceful inside, with just a Moroccan couple and a few tourists admiring the filigreed arches, walls decorated with intricate, multi-coloured, hand-cut zellij (glazed tile) patterns, beautifully calligraphy of verses from the Holy Quran, cedar lattice and intricately carved wooden eaves and awnings.

Medina of Fez is the largest automobile-free, pedestrian-friendly area in the world. Aside from hand-carts, once in a while we came across mules, donkeys and horses, carting food supplies and other stuff to the souks and construction material to the sites under renovation or repair. We walked down further and after a 10-minute stroll reached another massive brass entrance door of Madarsa Bou Inania at Rue Tal’a Kabira.

Built by Sultan Bou Inan in 1357, the madrassah was restored in the 18th century and again during 1994 to 2004. Another gem of Islamic architecture, its grandeur artistry displayed in stone, marble, plaster, wood and ceramic is breath-taking. All these historical places, restored in their glory, preserved and maintained so meticulously, made me wonder why we, in Pakistan, have failed to preserve our heritage, let many of the historic structures come to ruin, and why the restored structures indicate lack of skills, poor aesthetics and apathy towards the original finesse? One of the reasons on reflections after my visit to Morocco appears to be the lack of continuity of historic craftsmanship in Pakistan and a disconnect between the past and the present. Moroccan society has preserved their traditional arts and crafts and refined the skills through new tools, technology and training.

Another factor that seems to have played a role in the preservation of traditional crafts in Morocco is artisans’ cooperatives. After the visit to Madarsa Bou Inan, our guide took us to Herboriste Zaouia, a shop full of herbs, argan oil products, lotions, organic soaps and cosmetics. This was an outlet of a women’s cooperative, we were told. An old woman sitting on the floor with baskets of organic ingredients was crushing argan nuts. I learned that there are around 12,000 cooperatives, mostly of agricultural products. Of these, argan oil products are prepared by women’s cooperatives. In Morocco, artisans’ cooperatives date back to 1930s. After the land reforms in 1972, the state encouraged the formation of agricultural cooperatives. A supportive legal framework has led to a flourishing of cooperatives in recent years. From the young saleswoman at Herboriste Zaouia, I bought some zafraan, kalonji, and organic soap.

Explore: Sidi Bou Said — the blue and white Tunisian town named after a Sufi saint

The next morning, we set out to explore the city of Fez outside the medina, to have a look at the new city. Our taxi driver, a middle-aged man called Abdul Qadir, drove us first to the southern Burj (tower). The tower was closed. The structure looked ancient with its mud-coloured stone walls and iron-grilled, arched-shaped roshandaan, indicating restoration, good upkeep and care, quite unlike historic structures in our country. Built on a hilltop in 1544 by the Saadian, the ramparts provide a panoramic view of Fez al-Bali and Fez al-Jadid. From here, you can have a holistic view of the city of Fez. The historic city, Fez al-Bali, was founded on the right bank of the Jawhar river by Idris ibn Abdullah in 789. The new city, Fez Jedid, I learned, dates back to 1276. It is amazing how these two historic parts blend and connect with each other and with the new urban spaces that have been added to Fez Jedid in modern times. There were a few tourists at the fenced terrace. We looked down at the sprawling medina, the rooftops embellished with satellite dishes, the winding highway and the road network leading to new urban spaces.

From the south Burj, the taxi driver took us to a ceramics workshop Artargile — located at Hay Lala Yakout in the potters’ quarter Ain Nokbi — where pottery and mosaic-tiled objects such as fountains, water basins, tables, fireplaces, etc. are handcrafted. Owned and run by the Lahkim family of artisans, the workshop had several sections for processes of pottery making and zellij tile work. A guide took us to each section. He told us that the potters’ quarter was located near the souks but owing to pollution from the kilns the government moved it outside the medina near the southern ramparts. The clay is sourced from the surrounding hills, soaked in water for days, kneaded and wedged, put into forms through potter’s wheel, dried in sun, baked in a kiln, glazed, decorated through drawing and then meticulously painted. We saw several women in the painting section. We also saw the making of zellij the mosaic tile-work: how square-shaped small tiles, painted on one side, are chiselled into tiny geometrical pieces and then put together to make a pattern.

The Artargile outlet had very expensive pottery and objects d’art on sale. I understood that the company was paying commission to the drivers who bring visitors to the workshop and the outlet. We bought a couple of small objects. The visit was worth it. Our taxi driver then took us to Chouwara Tanneries. Located at Hay Lablida, rue Chowara near the Madarsa al-Saffarin, in the old city along the river, the tanneries were built in the 11th century. We were taken to a three-storey labyrinthine building comprising leathercraft shops and narrow staircases leading to a couple of terraces. Everyone going upstairs was given mint twigs to ward off the pungent smell of the tanneries. The tanneries are run jointly by 20 families who live in the surrounding buildings, the guide told us.

From the terrace we had an amazing view of the ancient tanneries. Square-shaped stone vats were filled with white liquids where the hides of cows, goats, sheep and camels are soaked for cleaning and softening. Brown circular stone vats held dyeing solutions made from natural colourants — red from poppy flowers, orange form henna, yellow from saffron, green from mint, blue from indigo, and brown from cedarwood. On the roofs of adjoining buildings, hides dyed yellow lay in rows for drying. We were told that this month (July) of the year is suitable for dyeing shades of brown, grey and yellow. The spring months are allocated to vivid colours such as red and green.

On our way back to the guesthouse, the driver showed us the Royal Palace دار المخزن, spread on 80 hectares. The palace has seven arched golden gates leading to beautiful gardens, mosques and a 14th-century madrassah, we were told. The tallest and the biggest brass gate, ornamented with zellij tile work and cedar wood carving, was being cleaned when we visited it. The palace is not open for public viewing. The King uses the Palace when he visits Fez.

The taxi then drove through the Jewish quarter Mellah located near the Royal Palace. Literally meaning ‘the saline area’, Mellah was established in 1438 to house the Jews driven out from Spain. Almost all Moroccan Jews have now emigrated to Israel, the US and Canada. “Rich merchants have now opened gold jewellery shops in this area,” the driver told us. Morocco had the largest Jewish community in the world until 1948. “Very few Jews have remained in Fez,” the driver said. A synagogue still functions for those who opted to stay.

A destination on our ‘must visit’ list was an English bookstore in Fez. We did not come across many bookstores anywhere. The few book shops we encountered inside the medinas of various cities and outside had books only in Arabic or French languages. We wanted to buy books by Moroccan authors translated in English, or books about Morocco written originally in English. We came to know about the American Language Center, which has an English bookstore on its premises. Through the help of Google maps and the taxi driver, we reached the language centre. The courtyard and garden bustled with activities: young Moroccans boys and girls, fetching tea and snacks from the canteen, sitting in groups, proceeding or coming out of the classrooms. We were thrilled to find its bookstore full of African-Arabic literature translated in English and books about Morocco. We stayed for a long time browsing and deciding which book to buy and which to let go for want of budget.

Just across Derb al-Mitr, the entrance leading to Riad al Tayyur, was an alleyway that opened to a souk dotted with cafés and tea shops. The man who served lunch at a café told us about the music sessions in the afternoon. “You should come. It is good music. You will like it.”

In the evening we were taken upstairs. It was a small dining area and at the front were seated the ensemble of the musicians — three young men in skullcaps. The one in white dress held iron castanets called qraaqab with a drum in front of him. The man in the centre with gold-rimmed black waistcoat and matching trouser, was playing a three-string lute hajhuj and the youth in green t-shirt was singing gnawa, a form of ancient African-Islamic music accompanied with Sufi poetry, akin to a qawwali, I would say. We were served green tea in tumblers half filled with fresh mint leaves. A woman, looked like she was from east Africa, rose from her chair and started to whirl — with her hair loose — at the rhythmic lyrics.

Next morning, it was time to leave the enchanted city. We packed our bags. The man in the riad helped us carry the bags to Derb al-Mitr taxi stand. The taxi dropped us at the train station. As the train proceeded to Marrakech, I kept wondering about the Fez medina. I had never seen such a city anywhere in the world: a city built more than a thousand years ago by Muslims, never demolished but continually restored, repaired, renovated; the medina has narrow cobble-stoned alleys as well as wide mosaic-tiled beautifully covered streets as in modern shopping malls. Souks are organised around merchandise and services. You would find quarters of meat sellers, vegetable and fruit vendors, kitchen utensils, tailors, tile-makers. We even came across an entire souk devoted to the preparation of wedding dresses and wedding paraphernalia. The historic city is sustained until today on traditional industries — tanneries, ceramics, textile, soap-making, flour mills, woodwork, and is served by efficient networks of utility services — sewerage, garbage disposal.

Culturally evolving, the medina has embraced changing times — empowerment of women and the emergence of female-headed households. I remember different shops in the medina run by women. A female ceramics shop owner, confident and cloaked in an abaya, from whom we bought pottery, told me she was managing the shop since the last 12 years with the help of her daughter and a saleswoman. Perhaps, the only change that has come about relates to the socio-economic status of its residents: most of the rich have moved to the new neighbourhoods outside the medina while retaining or selling their mansions to the hospitality industry. Remember, you cannot park your car in the medina. There is no space for automobiles. The middle and lower-middle-class and well-to-do merchants have remained for the old urban fabric still seems to provide a strong support network and a sense of collective identity, and of course, economic opportunities.

Wandering through Marrakech, ‘Africa’s capital of culture’

As our train proceeded from Fez to Marrakech, the pink city, I wondered what Jama al-Fina, the square in Marrakech’s old medina, would be like. Just before our journey, I had discovered a novel by a Moroccan writer Youssef Fadel, A beautiful white cat walks with me — a compelling, eerie and grim story of Sanawat-ar-Rusas (the years of lead), the reign of King Hasan II (1960s to 1980s) marked by political repression and violence. A masterpiece, this novel is a story of those years told by a father-and-son duo. A king’s private jester at the royal court, the father had begun his career as a story-teller at Jama al-Fina.

The taxi driver dropped us at Derb Asra entrance of Jama al-Fina in Kennaria, a neighbourhood adjacent to Jama al-Fina, and helped us get a man with a hand-cart to carry our bags to Riad Malida inside the medina. The wide street closes to traffic in the afternoon, we were told.

Listed by Unesco as one of the ‘Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity’, Jama al-Fina, provides a unique cultural space to citizens to engage in diverse activities and spectacles in addition to trading through weekly and daily markets. We had arrived in the evening. Jama al-Fina is a place to wander and explore with eyes wide open: there are so many sights and sounds and smells to take in. Tired after an eight-hour journey, we headed straight towards Café de France where the person from the riad said they would wait for us to guide the way. The place jostled with people. Dazed with fatigue, it was impossible for us to identify the man in the crowd so we got on Google Maps, entered one of the alleyways, and breathed a sigh of relief when we spotted the Riad Malida where we had booked a room.

The enormous brick-laid square, Jama al-Fina is lined on one side with hotels and café terraces. In between, narrow streets lead to the maze of Marrakech historic medina founded in 1070 by Abu Bakr ibn-e-Umar. On the far end, just opposite the souks, stands Jama al-Kutubiah. Horse-drawn carriages are lined on one side of the square opposite several public buildings adorned with red flags. All structures are hues of pink, peach and red. The pigment comes from local clay found in the surrounding areas and the uniformity is attained through a building regulation. As the square comes fully alive only in the evenings, after breakfast we decided to first explore the city outside the medina.

At 11 a.m., the square appeared empty, with only the fruit-juice sellers and dry fruit canopied stalls opening up. A few vendors were settling down with their wares.

We headed towards Avenue Yacoub el-Mansour to visit Marjorelle Garden located nearby. Conceived as a ‘botanical laboratory’, a garden and a villa, the place was designed and created by the French painter Jacques Marjorelle over forty years beginning from 1922. When he left Morocco in late 1950s, it fell to ruin. Later, French designer Yves Saint-Laurent purchased the property, restored it and sought the assistance of Abderrazzak Benchaabane, the famous Marrakech ethnobotanist and garden designer, to extend and enrich the site.

We strolled the many tiled walkways, admiring the several small gardens full of bamboo, cacti, palms, jasmine, bougainvillea, coconut and banana trees, and the foliage growing underneath. There were benches to sit, to rest and admire the plants. The pond in front of the blue villa, full of blooming white water lilies canopied by trees sparkled with flecks of light. The Marjorelle Garden has 300 species of exotic plants collected from five continents. It also houses a small Islamic Art Museum, a Berber Museum and the Yves Saint-Laurent Museum and a shop. Because of its French origin and its association with a famous fashion designer, the Garden looked too small for such an influx of tourists. We would have preferred a less populated garden.

Menara Gardens, in comparison to Marjorelle Garden and much to our relief, was totally bereft of tourists. Located three kilometres southwest of the medina, in the backdrop of the Atlas Mountains, Menara Gardens were built in 1130 by Abd al Mu’min. The Gardens, spread over a very large area, comprises fruit orchards, olive groves and cypress trees planted around a grand pavilion, a big rectangular artificial lake, and a small, green-tiled, pyramidal-roofed menara.

We traversed the vast promenade in the sizzling heat and headed towards the menara. After a little rest under the shade of a food stall, we bought the tickets and went inside. A cool chamber with beautiful windows and arched doors opening to the lake welcomed us. Inside, it was empty and we sat on the window sill for some time. Upstairs was a terrace and from here you could have a panoramic view of the surroundings which was not lush green. Trees were sparse. We came out of the menara and strolled down the promenade. On the right were shady olive groves that appeared to stretch beyond. Several Moroccan families were having a picnic, children playing hide and seek among the trees and elders relaxing on mats and enjoying home-cooked food. We spotted a couple of students bent over books studying in the nooks.

Outside the medina, we visited a historical gem located at Rue de la Kasbah: the tombs of the Saadian dynasty which ruled Marrakech from 1578 to 1603. The burial ground comprises two mausoleums, courtyards and gardens. When we entered a narrow, pink-hued mud-walled passageway that opened into a courtyard leading to the rooms, I did not expect the burial chambers to be so magnificent. The main room has 12 grand marble columns supporting the arches. Intricately carved cedar wood ceiling, delicate plaster filigree, colourful zellij tile-work, Quranic verses etched in marble, wood and plaster: from floor to ceiling, every nook and corner of the structure indicated incredible skills of master artisans. There are 66 graves inside the mausoleums and more than 100 laid out in the gardens. I learned the tombs were kept hidden, untouched, left to ruin by the later rulers until the site was re-discovered through aerial photography in 1917 and restored.

The Saadian tombs reminded me of the Makli Necropolis in Thatta, which I have visited four or five times. My last winter visit to Makli — one of the largest funerary sites in the world — revealed some restoration work and introduction of a vehicle to carry visitors from one cluster of tombs to another spread over a large area. Makli’s tombs, inscribed as a Unesco World Heritage site, dates back to 1335, more than 200 years older than the Saadian Tombs. I wished we would have been able to restore this burial ground to its eminence as a historic site worthy to be preserved, protected, and visited by us as well as those visiting the country.

Another historic site we visited in Marrakech was the Bahia Palace at Rue Riad Zeitoun el-Jadid. Built in the late 19th century, Bahia (brilliance in Arabic) Palace has a number of courtyards, gardens with fountains, salons and outbuildings spread out on five acres. The large rectangular courtyard has arched green-and-golden lattice colonnade on three sides and blue-green geometric-patterned zellij tile floor. I wondered about the thousand human stories that would have unfolded in now-empty rooms, bereft of all objects except beautiful fireplaces, carved ceilings, and stained-glass windows and doors.

Morocco’s many cities take pride not just in the historic sites but offer glimpses to new initiatives in the preservation of arts and culture and the contributions of its peoples, both men and women, young and old. One such initiative we came across in Marrakech was the Women’s Museum or Musée de la Femme.

Inaugurated in March 2018, the museum serves as an archive and documentation centre and a space where Moroccan women display their creative works. Located at the historic district of Sidi Abdel Aziz in the heart of the medina, the museum was running an exhibition titled The Pioneer Women when we visited it in July.

There were three women whose work and achievements were highlighted in the exhibition. The first was Malika Al-Fassi, a journalist-activist and a politician. Malika was the only female out of 66 signatories to vote for and signed the Manifesto of Independence of Morocco in 1944. The second was Izza Genini, a documentary filmmaker whose works include films featuring indigenous and folkloric music from various regions in Morocco. The third pioneer Rachida Touijri is a self-taught painter and a chemical engineer. Her work is abstract and influenced by Sufism. The exhibitions are complemented by the museum’s traditional Moroccan textile collection.

The exhibits are spread over a very well designed three-storey small house-turned-gallery with narrow staircase and a dreamy aura. The museum is a member of the International Association of Women’s Museum. At the gift shop, a cloth bag with a Fatima Mernissi’s quote read: Dignity is having a dream, a dream that gives you a vision, a world where you have a place, where your participation, as minimal as it is, will change something. I left the museum wishing to have such a museum in Karachi. Perhaps, one day young pioneers of our city would create such a place.

Another amazing place we discovered in the same neighbourhood — located between the Ben Youseff Mosque and the Ben Youseff Madarsa — was Dar Bellarj, a centre of art and culture housed in a traditional riad. Originally a foundouq (a mixture of musafir khana and a stable for animals) used by a man as a sanctuary for injured bellarj (storks), the building is now devoted to the protection and promotion of Moroccan culture by the Dar Bellarj Foundation, a non-profit organisation.

Opened in 1999, the renovated riad has an impressive courtyard with a fountain, surrounded by four large rooms and arched passageways decorated in traditional Moroccan architectural style. When we walked in, all the doors were open and there was no ticket booth. The rooms had wall installations comprising black and white photographs, artistically framed and collaged together reflecting the life as lived on the streets by the Moroccan youth, women and men. We learned that the foundation arranges thematic exhibitions, organises storytelling sessions, folk music concerts, and events related to poetry, song and dance, literature and drama. In the afternoons, it runs workshops on painting, model-making, music, etc., for both adults and children.

Again this fascinating cultural centre made me wonder why we could not save even one old building on Karachi’s M A Jinnah Road and turn in to a similar space. I know urban planner and architect Arif Hasan and his team at the Urban Resource Centre strove to rehabilitate an old building near Prince Cinema into an urban resource centre but in vain. The skeleton of the façade stands till today, reminding me, whenever I pass by the busy road, of the sad, greedy way we have treated the city’s heritage.

We then proceeded to have lunch in the Zwin Zwin café and restaurant that we had identified with the help of the internet. Located at Rue Riad Zeitoun El-Kedim, I found the café’s blending of modern décor with traditional aesthetics, simple colour scheme and the terraced lounges cosy and refreshing. The café’s walls were adorned with paintings by local artists, depicting Moroccan life and people. It was not just in Zwin Zwin café but in other small tea-houses and dhabas that I had come across some very good works by local artists and reproductions of fine Moroccan paintings.

In the evening, we sat on the terrace of Café Zeitoun, gazing at the hustle and bustle of Jama el-Fina. Famous for its fine and authentic Moroccan cuisine and panoramic view of the square, Café Zeitoun did not disappoint us and we returned to it a second time, on the last evening of our stay in Marrakech. After delicious food, we strolled down the square, looking at the many attractions the place holds for locals and tourists alike. We passed by a few snake charmers sitting on faded rugs playing flute to coiled cobras, a man with a monkey perched on his shoulder, men selling spices and dry food, a woman on a stool sewing a cap like the many spread out in front of her for sale, and young girls with their faces hidden in niqab painting henna on the hands of women.

We also spotted a bespectacled young guerrab (water-seller) in a traditional red dress, brass cups and a leather water-bag. We did not come across any story-teller, though. I later learned that the historic Moroccan art of oral story-telling is now on the decline. Some young Moroccans are trying to revive it but in cafés and cultural centres rather than in open spaces such as the Jama el-Fina. There was no street performer either at the square. Like the one whose story I read in A beautiful white cat walks with me: the street performer turned king’s jester, a character inspired by the real private jester to King Hassan II.

Perhaps the fine art of novel-writing is slowly substituting the thousand years old tradition of oral storytelling (hikayat) in modern Morocco. Stories of political suppression, brutality and torture inflicted during the ill-famed Years of Lead under the reign of King Hassan II are told by several writers in haunting, magical narratives such as in The blinding absence of light by Taher ben Jelloun (2004) and Youssef Fadel’s A rare blue bird flies with me (2013) and he recently released A shimmering red fish swims with me. Mahi Binebine, another famous Moroccan writer, in his novel The court jester (2017), tells the story of his father who served as the King’s jester and his brother who was locked up in the prison of Tazmamart for 18 years for his participation in the coup attempt in 1971.

Thoughts on Morocco

How did Morocco heal its past wounds and get on with its journey as a modern nation? I wondered. Morocco has many challenges: Literacy is not universal (74%); poverty (15%) is still there. Regional inequality between rural and urban and between Berber and Arab ethnic groups is a matter of concern. The ongoing conflict in Western Sahara between the rebel Sahrawi national liberation movement and the Moroccan Kingdom has resulted in denial of basic rights to the residents and continuous state suppression.

A weak parliament and concentration of power in the Royal House is considered to be the root cause of many ills. Still on the surface, to a traveller like me, the country appears pretty functional, progressing on modern lines while retaining a connection to the rich Islamic past.

A cursory reading on Morocco revealed a few things that to me appear to have worked out. Such as the Moroccan Equity and Reconciliation Commission (ERC), founded in 2004 to rehabilitate and compensate the victims of human rights abuses committed by the state during the Years of Lead. Though the Commission has been criticised for several failings, it investigated more than 16,000 cases and distributed $85 million to the affected individuals.

A 2004 code of personal status (moudawana) granted rights to women which gave impetus to women’s education and their enhanced economic participation. Another key step, it seems, has been the new constitution adopted through referendum and the reforms the Kingdom is pursuing towards democratic governance since the uprisings and protests of Arab Spring 2011. Based on the concepts of decentralisation, participation and public service provision, the reforms, despite sluggish implementation, have kept public discontent at bay.

The aspect of Moroccan society I wondered most about, during my travels, was religious tolerance whose manifestations I came across in all the cities I visited.

The reasons behind the tolerant attitude towards religious, ethnic, and cultural diversities, I think, include the religious homogeneity in Morroco: 99 per cent are Sunni Muslims belonging to the Maliki school of Islamic jurisprudence. The second is the control of the state on religious institutions. The Ministry for Auqaaf and Islamic Affairs is controlled by the monarchy. Friday sermons are regulated since 1984. After the Casablanca terrorist attacks in 2003, several initiatives taken by the state, such as training of imams, building of new mosques, renovation of old mosques, induction of women as preachers, establishment of a fatwah centre and lately the Institute for Training of Imams, Morchidines and Morchidates (2015) have helped spread the message of moderation and peaceful coexistence. I learned of the sacking of imams who did not adhere to the guidelines for sermons and of the founding of the National League of Religious Employees — a union of a sort — in 2012 by one of the sacked preachers.

Morocco is not just a historic place, emblematic of Islamic history, architecture and urban space and living; it is a continuously evolving, modernising society, coming to terms with the challenges of the time and striving to achieve a balance with the conflicting forces of modernity and tradition.