Euresia Review

by Dr. Mohamed Chtatou

Morocco is a crossroad country, a country where different cultures, civilizations, languages, beliefs and religions meet and coexist in total harmony. It has been this way since the dawn of times.

The country distinguishes itself by Amazigh/Berber, Arab, Jewish, Mediterranean and African cultural influences that Moroccan culture is hugely proud of nowadays and which is inscribed in gold in the Moroccan constitution of 2011 (1). To this cultural richness is added an interesting geographical diversity. In fact, Morocco counts various landscapes, from deserts to mountains to fertile plains framed by maritime coasts of 3,500 kilometers long.

At different periods of its millenary history, Morocco was invaded by the Phoenicians, the Carthaginians, the Romans, the Vandals, the Arabs, the Portuguese, the Spanish and the French. Even the Germans, angered by the sharing made during the Algeciras Conference of April 7, 1906, that had placed Morocco under the protection of major European powers (twelve, among which France, United Kingdom, Germany, Spain and Italy) under the guise of reform, modernity and internationalization of the Moroccan economy and did not give Germany any piece of the “Morocco cake”, came off to the Moroccan southern coast to show their dissatisfaction, by bombarding the city of Agadir on July 13, 1911 by one of its infamous gunboats bearing the name of Panther (2).

These multiple forced meetings with other cultures, languages and races have cultivated among Moroccans an advanced taste for the other and his civilization and, by consequence, an aversion for cultural diversity and tolerance.

So, cultural diversity and tolerance are not new concepts for the average Moroccan, but these notions are well buried in his past, his subconscious and culture. They can be easily detected in his daily verbal language, his body linguistic expressions and even his religious beliefs, without forcibly forgetting his material and immaterial patrimony (3).

A Cultural Melting Pot

At the northeastern part of the town of Ksar Kabir, that is located at the northwestern part of Morocco, is a tiny village called Tatoft, where resides a religious brotherhood of a singular nature: the Jajouka (4) of Ahl Srif, A group that practices spiritual trance music that is supposed to cure followers that are possessed by evil spirits, chief among which the jnoun (5).

Arian Fariborz introduces the Jajouka musicians in the following terms (6):

“Joujouka is a small insignificant village of 500 people on the edge of the Rif Mountains in northern Morocco: its whitewashed houses have blue painted doors and window frames. A stony path lined with luxuriantly overgrown cactuses and sheer rock leads over a hill to the village mosque and the school.

But this isn’t an ordinary village. Joujouka is the home of a musical elite whose ancestors came from Persia in the ninth and tenth centuries and who are still renowned for the magic and healing effects of the sounds they make.”

These valiant musicians from this village are descendants of the Sufi saint Sidi Ahmed Sheikh, who apparently came from the Machrek around the thirteenth century for religious preaching but ended up settling down with the Ahl Srif, arabized Amazigh/Berbers from the Rif, teaching them the virtues of Sufism and the art of using music to cure some psychiatric illnesses and disorders.

Since then, Jajouka have abandoned agriculture, their old occupation, to give their body and soul to spiritual Sufi music. As a counterpart for that, they get donations of seeds and money from their tribe every year in the summer, for their religious role of keepers of the mausoleum of the said saint and the perpetuation of his ancestral tradition of trance music within the region. It is a sort of dime or tithe.

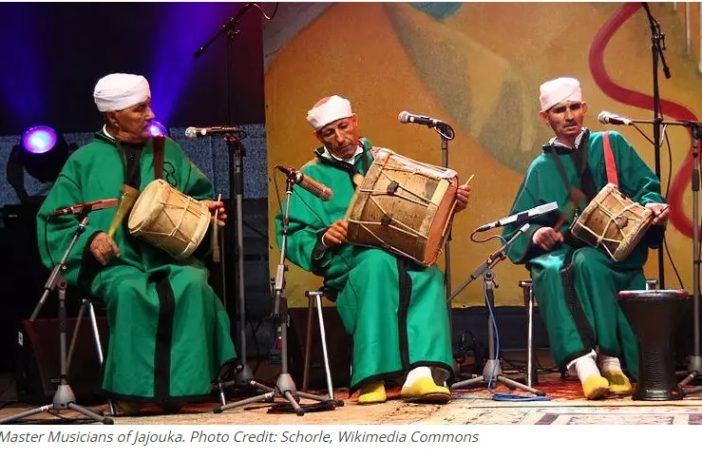

For a lot of Moroccans, the Master Musicians of Jajouka are vulgar ghayata (7) who wander around the souks to beg to rustic people for money. But, in reality, Jajouka are more than a group of souk players or weddings, baptisms and circumcisions party musicians, they are an example of cultural diversity and tolerance in Morocco of past and present times.

For some anthropologists, the Jajouka (8) are perpetuating pre-Islamic traditions that date from the time of the Roman Empire, such as the annual fecundity rites of the agricultural calendar. For others, the ghayata of this group reminds them of the ancient divinity Pan and of his aversion for sex leading, consequently, to abundance and fecundity. Indeed, in ancient Greek religion and mythology, Pan is the god of the wild, shepherds and flocks, nature of mountain wilds, rustic music and impromptus, and companion of the nymphs. He has the hindquarters legs, and horns of a goat, in the same manner as a faun or satyr (9). For the ethnomusicologists, this group perpetuates a unique millenary music.

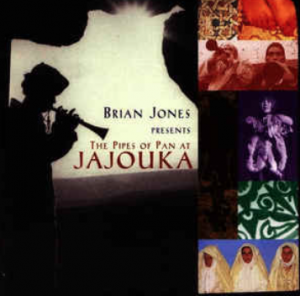

The Master Musicians of Jajouka have been revealed to the public in 1968 by Brian Jones, the star guitarist of the “Rolling Stones”, who had recorded the compositions of their ghaytas in an album titled “Brian Jones Presents the Pipes of Pan at Jajouka.” Many other artists, such as Jimmy Page, Ornette Coleman (10) and Peter Gabriel had called on them for the originality of their music. The group had, also, an influence on the poets and the writers of the “Beat Generation,” (11) such as Williams Burroughs and Paul Bowles, who met them in Tangier. These Moroccan musicians, also, appeared in the movie “The Sheltering Sky” by Bernardo Bertolucci, after a suggestion from Bowles.

What is important in the Jajouka musicians, more than other musicians of the same genre is that this group has successfully assimilated cultural diversity in their musical, cultural and spiritual traditions. Jajouka (12) are adepts of Sufi music, a music that is supposed to free the soul of its corporal envelope and allow it to overtly communicate with others. Thereby, their music is in reality a music that promotes dialogue with others and full brotherhood of men. Proof is that famous musicians of international renown such as Ravi Shankar, Randy Weston, Ornette Coleman and many others went to their village to meet them and appreciate with their own eyes and ears their ancestral art and share in their celebrations.

The Jajouka are, also known for their musical prowess in playing the oboe (ghayta), known as “circular breathing,” (13) a natural acquired gift that allows them to play air instruments for hours on end without tiring. (14)

The success of the Jajouka’s (15) tradition resides in the fact that their music, their trances and their religious practices have succeeded in a remarkable way to highlight the fraternity between men and the concordance of cultures instead of their discordance especially now that there are unfortunately multiple signs for possible future clash between civilizations. (16)

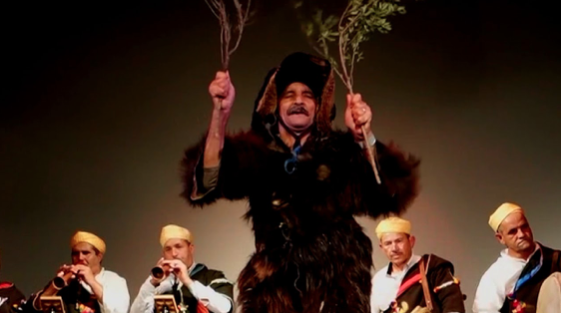

The Boujloudiya is a party successfully celebrated by the Jajouka every year in their village, during the sheep festival, Aïd al-Adha. This celebration of trance music, of dance and of theatrical representation celebrates fecundity, but it is, also, a party to thank God of his generosity towards man. The Boujloudiya is in fact a meeting point between Christian religion, with its concepts of celibacy and purity of the soul, and of Muslim religion, with its asceticism, its sense of sacrifice and of divine benediction (baraka) mingled with a substratum of pagan spirituality common around the Mediterranean Sea.

In reality, the practice of Boujloudiya dates back to immemorial times in the Mediterranean basin. The Boujloudiya finds its origin in Greek mythology with the god Pan who was the protector of shepherds, herds, and nature. His ardent love, also, earned him the title of divinity of fertility. In many Mediterranean regions, celebrations take place, even nowadays, at the end of the agricultural cycle which is reminiscent of the cycles of fecundity of the god Pan in the past. Pan is celebrated by trance dances and frantic races to fecund nature and human beings for the year to come.

This pagan practice was introduced in ancient Morocco by the Romans. In their mythology, the name of this god was Lupercus (17). Since, this practice is fully immersed in popular Moroccan culture, especially among the rural population, which practices agriculture for its subsistence.

What is interesting is that the temper and the philosophy of the average Moroccan throughout history is his open-mindedness towards the other and his culture even if this culture is in contradiction with his beliefs.

By nature, the Moroccan individual does not reject anything that comes from elsewhere; he tries instead to assimilate it by his own means and in his own context so that it does not appear to clash with his faith and tradition. In reality, it is a big capacity of adaptation with the other and his acceptance: a vivid illustration of the gift of dynamic multiculturalism.

When Sidi Ahmed Sheikh, the famous Sufi, who came from the east, arrived in the Tatoft locality of northern Morocco in the 13th century, he was subjugated by the beauty of the region and the friendship of its habitants, who were, predominantly, Amazigh/Berber people arabized over centuries. He taught them the Islamic religion, and while doing so, he understood that they had a love and a gift for music and that they were celebrating pagan rituals by the end of summer.

As a good Sufi, infatuated by open-mindedness and soul purity, he assimilated these practices into Islam and so the celebration of the rite of fecundity was moved on to the Hegira Muslim calendar to coincide with the sheep (sacrifice) festival. There, the celebration was called Boujloudiya or Boujloud in Arabic and Bouirmawen/ilmawen or Bouisrikhen/islikhen in Tamazight, because the principal character of the rite was wearing the skins of the sacrificed sheep.

Another principal character of the practice is no other than the beautiful village virgin that the god Pan tries to soften up to benefit from her sexual favors to fecundate her and fecund nature by the same mean. In the Islamized tradition of the rite, this woman is called Aicha al-Hamqa (“Aicha the crazy”), to minimize the rite and make it acceptable towards the shari’a and blame this illegal sexual act on her craziness, and show that it is not a practice acceptable in the Muslim tradition. Islam has also introduced the character of al-Haj (the man who made pilgrimage to Mecca) in the dance act, a man in white djellaba (a local long robe with a hood) to Islamize this pagan tradition but he has no particular role to remember in the whole theatrical celebration.

For Frank Rynne, the Jajouka continue relentlessly to practice their pagan rites under the ragged and orthodox cloak of Islam: (18)

“The musicians were described by Burroughs and Leary as a “4,000-year-old rock’n’roll band”. According to Gysin, the musicians held a secret, hidden even from themselves: they still practised “the Rites of Pan under the ragged cloak of Islam”. The “ragged” referring to the musicians’ poverty.”

This practice has been immortalized in the work of William Shakespeare (1564-1616) Julius Caesar, written in 1606. In fact, in the First Act of the Second Scene, Jules Cesar asked Antony, who was prepping for a religious race to touch the hand of Calprunia, his sterile wife, to have heirs for his vast empire. (19)

History And Legend

The Jajouka Master Musicians is a male group from Jajouka, a small village at the foot of the Rif Mountains, about 100 kilometers from Morocco’s main port city of Tangier. As residents of the small village of Jajouka in the hills of Jbala in northern Morocco, the Attar family (family of perfumers in Arabic) preserves one of the oldest known musical traditions on the planet. (20)

Recognized for their music by the Moroccan royal family for centuries, by jazz masters, rock gods, respected writers and high-level artists from around the world.

Actually, it is not the influence on Western culture that distinguishes Jajouka’s masters. It is the very complex rhythms and melodies that they begin to learn from their fathers in childhood, which, if practiced all their lives, allows them to become real ma’almin or Masters. These skills and secrets of Jajouka’s Master Musicians have been passed down from generation to generation and have gone through centuries of struggle and hard work.

If today these musicians are recognized worldwide, though unfortunately they are not well-known in their homeland, it is due to two important factors; Firstly, their music is probably 4,000 years old and the anthropological theater related to it is traced back to Greek mythology. Indeed, the American novelist and painter William Seward Burroughs described the Masters’ music as the world’s oldest music and was the first person to call the musicians a “4000-year-old rock and roll band.” (21) Secondly, their music has a universal message in that it calls for tolerance, brotherhood of men and love at a time when the world is very much tormented by violence and hate.

Neil Strauss in an article written for the New York Times describes the Master Musicians as follows: (22)

“Some think of jajouka as trance music, with its wailing double-reed pipes and frame drums, but Mr. Davis was attracted to it as fusion music. “I think of it as a mixture of Moorish melodies from the lost world of Andalusian Spain, a North African backbeat, and this survival of very old Arcadian music, the music of the ancient world. It’s a heady brew.”

Jajouka’s Master Musicians play a variety of folk music, old and newly written on traditional locally made instruments. Most of the compositions in their extensive repertoire are unique to the Attar family and their traditions in Jajouka. Boujloudiya, the trance music of the “father of the skins”, Boujloud, is played in the village during the festival of Eid al-Kebir, Khamsa ou Khamsine, their oldest and most complex musical number, has been played for centuries by the Jajouka Masters for the sultan, both in his palace and on the battlefield. Hadra appeals to the spiritual energy of the saint buried in Jajouka, Sidi Ahmed Sheikh, who would have blessed the Attar family and their music with baraka and the power to heal people with mental and physical illnesses.

Jajouka’s Master Musicians are Sufi trance musicians. They play a form of trance music that is used to heal mental disorders and psychological mistrust and crude violence. Every year in the village, a boy is sewn into goat skins to dance under the name Boujloud, which appears to Westerners as Pan. The goat god playing the flute is the protector of the shepherds who brings fertility to spring. The musicians play ancient music to bring Boujloud back to his cave. The beast soothed by their music, they can expect a good harvest. Women affected by its palm leaf fronds will have healthy children and the whole world will bask in happiness and bliss.

The remarkable music played by Jajouka’s Master Musicians is thousands of years old. In the 13th century, as the Sufi saint Sidi Ahmed Sheikh arrived in the village, he wrote music for the ancestors of the Masters that could heal disturbed spirits. Today’s Masters are blessed by the baraka or the spirit of their saint and use touch and prayer to heal.

Music itself is considered part of the Sufi tradition of Islam. Before the colonization of Morocco by France and Spain, the Master Musicians of the village were the royal musicians of the sultans. In past centuries, the Master Musicians of the village of Jajouka had been excused by the country’s leaders for manual labor, goat farming and agriculture, in order to concentrate on their music, as the powerful trance rhythms and buzzing woods were traditionally considered to have the power to heal by sound the sick and the disturbed.

Who Are They?

Most of Jajouka’s inhabitants are members of the Ahl Srif tribe. The Attar clan of Jajouka is the founding family of the village and the guardian of one of the oldest and most unique musical traditions. Jajouka’s music and secrets have been passed down from generation to generation, from father to son, according to some, for 4000 years. Jajouka’s musicians learn complex music, unique to Jajouka, from an early age. After many years of training, the musicians finally become ma’almins or Masters. They possess the baraka (good luck) blessing of Allah, which gives them the power to heal and the stamina to play the most intense and complex music there is.

Indeed, the musicians have the physical power and mystical gift to play their music for hours on end without pausing thanks to their innate ability to generate reinvigorating rhythms for the players and blessing hymns for the audience that enhances internal peace and tranquility.

For centuries, Jajouka’s Master Musicians have been employed by the Kingdom of Morocco as the king’s royal musicians. They had special papers detailing their rights as privileged citizens, which allowed them to remain the royal musicians of many leaders – even through French, English and Spanish colonization. All the while, the musicians would continue to play in and around Jajouka at weddings, Moussems (local music festivals centered on a saint) and for holidays such as Aid l-Kbir supported locally by farmers and respected through the entire Jbala region. As a matter of fact, the musicians were allowed to collect an annual tithing from their crops, a privilege they retained until the beginning of the 20th century.

Subsistence farming is the main activity of most villagers living in Jajouka. The main crops are olives, tillage with vegetables such as carrots, turnips, potatoes and sheep farming, which are grazed on common land. Poultry is raised by women. In summer, shepherds bring the herds to the highest slopes. They can be heard training on bamboo flutes for miles. High-quality livestock, chickens and olive oil are an important part of the economy in this area. There is also small-scale honey production by some enterprising villagers.

In recent years, electricity and mobile telephony have arrived in the village and there is a passable road that has reduced the cost of transporting essential goods to the village. The cost of transportation had made many items inaccessible or prohibitively expensive for villagers. Ahl Srif was also an area where kif (cannabis) was grown, but its cultivation has recently been banned. However, there does not appear to be an alternative cash crop for those who depended on it in the past.

Jajouka And The Beatniks

The Jajouka Master Musicians are known for their pre-Islam trance ceremony evoking the ancient rites of Pan, the goat-legged fertility god of ancient Greece. The music of the Master Musicians has been described as “a storm of sound” (New York Times). Embraced in the 1950s by artist Brion Gysin and writer Paul Bowles, the village of Jajouka became Mecca in the 1960s for celebrities such as the Rolling Stones, Ornette Coleman and Timothy Leary, etc.

Brion Gysin, William S. Burroughs, Steven Davis and other writers linked elements of Jajouka’s musical traditions to Greek and Phoenician ceremonies. Burroughs dubbed Jajouka’s master musicians “a 4,000-year-old rock band.” However, he was probably linking the unique rites of Boujloudiya, performed in Jajouka during Eid al-Kebir, to Lupercalia, the ancient Roman celebration,rather than accurately dating the origins of the music itself. Bachir Attar, leader of the Jajouka Master Musicians, whose father, El Hadj Abdesalam el Attar, led the band until his death in 1981, explains that the family’s most sacred compositions date back more than 1,000 years.

The Master Musicians of Jajouka have a long history recorded by Western artists. Arnold Stahl produced a disc, “Tribe Ahl Srif: Master Musicians of Jajouka,” recorded on site as part of a documentary film written and produced by Stahl. This double album was released in the early 1970s by the Musical Heritage Society. During the 1970s, the French label Disque Arion released a single album of the same music, produced by Stahl and entitled: “The Rif: The Ahl Srif Tribe.”

Both albums are credited to Jajouka’s Master Musicians (or Jajouka Master Musicians). The name Master Musicians of JaJouka was first used by William S. Burroughs in the 1950s, by Timothy Leary and Rosemary Woodruff Leary in the 1960s and 1970s, and by Brian Jones L.P. published in 1971. In the 1980s, the musicians were sometimes called Jahjouka’s Master Musicians, Jajouka’s Master Musicians and Joujouka’s Master Musicians in both articles and on official documents.

The Masters, Beatniks And Hippies

Two of the great influences of the Beat Generation, Brion Gysin, painter and inventor, and Paul Bowles, writer and composer, first heard Jajouka’s wild music in a moussem or festival near Sidi Kacem, Morocco, in July 1950.

Tangier, Morocco was then an international zone, where everything could and should happen. In this adventurous climate, the painter and writer Brion Gysin opened in 1954 the legendary and popular restaurant 1001 Nights in Tangier, located in a wing of the Menehbi Palace on the Marshan. Gysin hired Jajouka’s Master Musicians to play, dance and serve a largely international clientele. It was the time of the “interzone” of the Beat writer William S. Burroughs, described in his book “The Naked Lunch.”

In 1968, Brion Gysin brought his close friend Brian Jones, founder of the Rolling Stones, to Jajouka. Brian Jones sadly drowned in 1969, a month after his return from Morocco, and the album he recorded, “Brian Jones presents The Pipes of Pan in Jajouka,” was released two years later in 1971 and was reissued in 1995 and several times after even in Japan. The original album was very influential and led to dozens of people visiting the village in the following years, including jazz saxophonist, father of the Free Jazz, Ornette Coleman, who recorded the track “Midnight Sunrise” in Jajouka for his 1973 album: “Dancing in Your Head.”

In the late 1950s, Gysin and Burroughs lived at the Beat Hotel at 9 rue Git-le-Couer in Paris. Here, Gysin invented the writing method and Dreamachine (23) with Ian Somerville and worked with Burroughs, Somerville and filmmaker Antony Balch in film experiments on Cut Up on a soundtrack of Gysin’s Master Musicians. When the Rolling Stones were in Tangier in 1967, Hamri and Gysin met them and Hamri formed a bond with Brian Jones.

Brian went to Jajouka, where he fell in love with the music of Masters, although he said: “I don’t know if I have the stamina to withstand the incredible and constant tension of the festival.”

He returned in 1968 to record the Masters. Before his death in 1969, Brian had prepared the cover, and edited and produced the album of recordings he had made of the Masters: “Brian Jones presents The Pipes of Pan in Joujouka” was released in 1971, paying tribute to Brian’s memory and allowing a wider audience to discover for the first time the remarkable music of the Masters.

The Jajouka Master Musicians became an icon of the counterculture when Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones confessed that although he struggled to keep up with the “constant tension of the festival” during the performances, he did not have the energy to keep up with their frenetic trance music which he had registered in their small village at the foot of the Rif in Morocco Mountains in 1968. Their reputation was cemented when Rolling Stones Records released Brian Jones record of the Masters in 1971, and that reputation continues to this day unabated.

In January 1973, jazz musician Ornette Coleman recorded with the Masters. A small part of what was recorded was released on the 1975 album “Dancing In My Head.” Also in 1975, Hamri’s book, “Tales of Joujouka,” was published. Thanks to Rikki Stein, the Masters first played in 1980 at Worthy Farm, the Glastonbury site, as part of a three-month tour that included a week-long residency at the Commonwealth Institute in London.

For Andrew Gilbert, The Master Musicians of Jajouka are an old musical dynasty that inspires international artists: (24)

“If the Master Musicians of Jajouka had a Facebook page, the ensemble’s friends would include The Rolling Stones, Ornette Coleman, Led Zeppelin and William Burroughs (in spirit at least) — and that’s just for starters.

Though the group hails from Jajouka, an ancient village in northern Morocco’s rugged Rif Mountains, its ecstatic, swirling sound has served as muse and inspiration for an international array of artists since modernist writers like Burroughs and Paul Bowles stumbled upon the music in the early 1960s.

Led by Bachir Attar, the scion of a musical dynasty that dates back more than 10 centuries, the Master Musicians of Jajouka perform at Neumo’s on Tuesday as part of a brief U.S. tour, an endeavor that has become increasingly daunting for Middle Eastern artists since Sept. 11, 2001.”

Sacred Brotherhood Music

The Master Musicians of Jajouka adhere to the traditional Sufi trance music of their patron saint, transmitted for centuries on end. After visiting the village in September 1969, Timothy Leary wrote an essay about his time with Mohamed Hamri and the Master Musicians in his 1971 book, Jail Notes, entitled “The Rock’n’roll Band of Four Thousand Years”. Leary based his central argument on Burroughs’ belief that the Boujloud ritual, played in Jajouka, owes its origin to the ancient Greek deity Pan.

The Jajouka brotherhood plays a form of reed music, pipes and percussion that relies on improvisation and complex rhythms, most of which are unique to the Jajouka clan. Their flute is called the lira and is considered the oldest instrument of Jajouka. The double-reed instrument is called the ghayta; it looks like an oboe, but has a louder and more penetrating sound. The drum is called tbel and is made of goatskin and is played with two wooden sticks. There is also another goatskin drum called tarija, which allows for faster virtuosity.

Frank Rynne writes about his unique experience at Jajouka and his immersion in their ancestral music in The Irish Times in the following words: (25)

“The music began with long plaintive notes segueing into repetitive refrains and hypnotic drumming. This music is haunting and unworldly. They played the tunes left by their patron saint, which the musicians and their ancestors have played for centuries to heal illness and mental disturbances. They continued for several hours until dinner was served on a large plate from which we all ate communally.

After the meal, the musicians produced long mahogany double reed horns called rhiatas, which are similar to oboes. Their massed sound carries for miles in the little hills of the Ahl Srif.

The musicians use long extended notes and utilise circular breathing techniques. The horn players divide into sections and play extended loops following a lead section. They are loud as any rock band.”

The Rite Of Boujloudia

This music is part of its essence in a fertility ritual, a variant that has existed for millennia but is perhaps the best preserved in Jajouka. Similar traditions exist in all Mediterranean regions where masked and frantic characters, at certain times of the year, spread panic and fear among the villages. Some theories, notably that of the19th century Finnish anthropologist Edward Westermarck point out the similarities between these traditions and the Roman Lupercalia festival.

In Jajouka, the rites are centered on a character named Boujloud and on the woman he is in love with, Aisha l-Hamqa related to the evil woman spirit Aisha Qandisha, popular in Moroccan folklore. Boujloud tries angrily to hit the musicians and spectators with fertility branches, but he is controlled by the powerful force of trance music of the Jajouka players. Boujloud holds branches in his hands and, in his frenzy, he could hit anyone. The women struck by him will surely be fertile in the future and with them the whole fields and land.

Aisha l-Hamqa dances frenetically to seduce him and make him express more desire and produce more abundance and fertility. This extraordinary character fits Shakespeare’s Hamlet (26) who feigns madness: (Act 3, Scene 4) Polonius to Hamlet: “Though this be madness, yet there is method in’t.”

After Eid al-Kebir, at the full moon, the musicians organize a festival during which this fabulous music is performed. It is characterized by a certain rhythm and melody and can be interpreted by many ensembles using different instruments such as ghayta and lira and even gambri and bendir. It can be performed at other times, at weddings and parties. Everyone can dance, but you have to look for the man with a hat and a goat’s skin. Boujloud could come out of nowhere and the dancer will only have time to see the bright and fierce eyes before he is forced to run.

Jajouka’s Instruments

Ghayta: Double reed horn with a series of apricot wood holes originally made in Ouezanne, a town in northern Morocco. It often, also, has a pin guard. Sometimes called the Arab oboe, variations of the ghayta can be found in other parts of the world such as Persia (Ney), India (Shehnai and Nagaswaram), Tibet (Gyaling), Thailand (Pi) and China (Suona).

Tbel: A double-skinned drum made in a variety of sizes. The drum skins are made of goatskin and played with sticks and hands.

Darbouga: Traditional smaller Arabic ceramic drum with a trap. Often found all over the Middle East. It has a powerful sound for its size.

Gambri: Moroccan variations are also known as hejhouj. At Jajouka it is specifically pear-shaped and is known as loutar or gambri, while the Gnawa’s has a tendency to be rectangular. Even an oval shape is available. It has four strings traditionally made from goat intestines, but which are now often linked to nylon ropes. The instrument is usually played with a long curved pick, which adds to the attack and texture of the sound.

Turkish Lira: A common bamboo flute, similar to a recorder. It is made in Jajouka.

Kamanja: A violin played standing on the knee is usually played with gambri, drums and singing.

The Music Genres Of Jajouka

Khamsa ou Khamsine: Khamsa ou Khamsine literally translates into the number fifty-five in Arabic. This is the number of times of a very complex rhythmic cycle performed by the Master Musicians of Jajouka. It is also one piece with the same title Khamsa ou Khamsine which has the form of a suite with several sections reserved for major transits or events. The exclusive tradition of interpreting this piece belongs only to Jajouka’s Master Musicians and is perhaps among the oldest. In addition to being original and the oldest, it also testifies to the mastery of these instruments by the musicians, the ghayta and the tbel, as well as their intensive use in parallel. Because of its rhythmic and harmonic complexity, only the real ma’alam (master musician) can play it.

In ancient times, khamsa or Khamsine was performed by both small ensembles and an orchestra of up to 30 ghayta musicians and 20 tbel musicians. It is highly melodic, intense and beautiful.

Hadj Abdesalam Attar, the father of Bachir Attar, would lead the group by repeating the very complex rhythm by tapping his foot on the ground. In the past, when an important visitor came to the Sultan’s palace, this suite was performed in their honor as a welcome and an initiation. Some sections could also be played when the musicians accompany the sultan to battle as an anthem and prelude to action.

Hadra: Hadra means “presence” in Arabic, presence of good spirits and saints and the propagation of their goodness to men, dwellings, fields and animals. In the context of Islam, it is the term given to collective supererogatory rituals practiced by mystical Sufi orders. In many cases, it is accompanied by trance-inducing music. In Jajouka, it is a sacred music and perhaps the most important tradition preserved by the Master Musicians of Jajouka.

The Saint, Sidi Ahmed Sheikh, their ancestral spiritual leader, passed it on to them and blessed the music with a powerful healing property or baraka (divine gift). This is the essence of Jajouka: peace, harmony, love and tolerance. Many people suffering from physical and mental illnesses have been cured by Hadra music for hundreds of years.

Sometimes a mentally unstable man will be brought to the village, often with his wrists tied to a tree near the mausoleum of Sidi Ahmed Sheikh. The musicians play Hadra piece for long periods, sometimes several days, a week until he starts to wake up and actually listen to superior reasoning. When the musicians notice his reaction to the planned sound healing, the rhythm accelerates and builds to a crescendo to the point that the unstable individual begins to dance until possible collapse synonymous of healing and release of his soul from the fetters of evil possession. As a result of this prayer, the instruments are passed over his body and, when he wakes up, he is deemed cured. This music has a slow introductory section, with a long, complex and soothing rhythmic loop that supports an equally long and complex melody. This slow introductory section is followed by a faster rhythmic version. Later, the dance section follows, to be concluded by another slow section.

Boujloudia: When the feast of sacrifice arrives on the tenth day of Dhu al-Hijjah month of the Islamic calender, the villagers of Jajouka know that Boujloud will be upon them. That night, Boujloud (the one who wears skins) is not only covered with tree branches and shrubs are attached to him. A bonfire is built in the centre of the village square, the only light will come from its flames. Once the ghaytas have started to play, there is not even a fraction of a second of silence for the rest of the night; there is no singing, only the shrill of twenty oboes supported by the inexorable beat of the drum tbel. One does not see Boujloud arrive; he suddenly finds himself between the fire and the circle of spectators, a dark figure tapping his bare feet on the earth, the dancer holding in his hand a branch, occasionally striking a spectator. The screams caused by his gesture are covered by music. What began as a concert became a visible spectacle, a ritual. As this metamorphosis has taken place, the element of time is no longer present. Finally, when the observer’s tension decreases, Boujloud disappears in the same way he entered the ring. The show has become a concert again, the performers have entered the notes they play and it is now that they produce the most passionate and exciting moments of the night: the endless sweet trance leading to trance. A legend surrounds Boujloudiya: if the Master Musicians stop playing the flute, the world would come to an end because such music soothes life and keeps evil away, far away.

Pan rites certainly took place in Jajouka and elsewhere in pre-Islamic times. Their significance here is that this pre-Islamic survival is unique in the way it looks at a tradition and spirituality that were common to people before the advent of organized religions.

Taqtouka al- jabaliyya: It is the daily folk music of the Jbala country, played on gambri, lira, kamanja and tbel. They are popular songs about unrequited love, wine-drinking and debauchery but also piety, love of the prophet and of the land of ancestors. It is a softer and more ethereal melody of everyday life.

The Master Musicians play this music for festive occasions such as weddings or baptism or tribal reconciliation. The Taqtouka music is accompanied by dancing performed by young handsome men or boys dressed in women clothing while spectators sip at glasses of sweet mint tea and smoke pot from their traditional long earthen pipes known as sabsi.

Traditionally Taqtouka music is a genre that celebrates all that is illicit haram in Islam: wine known as sahba, sex, sexy dancing and herb-smoking. People will spend a whole night indulging in illicit practices, once in a while, and the next day at dawn they will make big ablutions and resume praying and being a pious Muslim and good family chief and straight husband.

Royal recognition

The Master Musicians of Jajouka have in their possession sealed decrees that gave them the title of playing for the reigning Sultan of Morocco. This music is completely different from the passionate and frenzied Boujloudia and is played on small bamboo flutes, gambri, violin and drums. They took over the leadership of the army and announced the sultan’s arrival in a new city. This music was also to wake up the sultan in the morning, make him fall asleep at night and, in general, create the atmosphere in which the sultan lived, ruled and dominated his subjects.

These decrees were addressed to the musicians with extraordinary respect and freed them from all work, allowing them to take tithing from all cultures cultivated around Jajouka. This vital task was lost at the beginning of the last century with the partition of Morocco, at the beginning of the twentieth century, by France and Spain, when the Jajouka village found itself on the wrong side of the border and cut off from its beloved monarch.

Jajouka’s Master Musicians are all descendants of the same family, the Attars. Attar is a Sufi motto and a deeply mystical name that means “perfumer”. Long before the current Alawite dynasty of Moroccan sultans, Master Musicians traveled with the sultans as royal musicians, known at times as the Khamsa ou Khamsine orchestra, whereby the number is synonymous in the royal language of music of merriment in the court and glory in the battlefield.

Their task was to be at the head of the army while in progress to battle and announce in fanfare the sultan’s arrival in a new city. They had very old papers from the king that explained their duties and rights to the palace: play the king in bed at night; play for him in the morning; and play at the mosque when he went to Friday prayer on his horse. These papers were renewed when the Alawite family, the ancestors of the current Moroccan king, came to power in the 17th century.

You can follow Professor Mohamed CHTATOU on Twitter: @Ayurinu

End notes:

- https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Morocco_2011.pdf A sovereign Muslim State, attached to its national unity and to its territorial integrity, the Kingdom of Morocco intends to preserve, in its plentitude and its diversity, its one and indivisible national identity. Its unity, is forged by the convergence of its Arab-Islamist, Berber [amazighe] and Saharan-Hassanic [saharo-hassanie] components, nourished and enriched by its African, Andalusian, Hebraic and Mediterranean influences [affluents]. The preeminence accorded to the Muslim religion in the national reference is consistent with [va de pair] the attachment of the Moroccan people to the values of openness, of moderation, of tolerance and of dialog for mutual understanding between all the cultures and the civilizations of the world.

- For more details, see « Chronique de la Conférence », MEE, TR XX/38, Caisse 334.

- For people from the Rif, aghrib, “the other, the stranger, the traveler, etc.” does not only benefit from the protection of the clan or of the tribe, but, also, benefits from the right to work and own a house on its territory. This is part of the honor code of each clan and tribal entity whose bards sing, with pride, during festivities such as marriages, circumcisions and baptisms.

- Cf . M. Chtatou ; « The Magical World of the Master Musicians of Jahjouka » in BRISMES Proceedings of the 1986 Conference on Middle Eastern Studies. Ed. L.D. Lanthan. Oxford : British Society of Middle Eastern Studies, 1968.

- Jnoun, pl. jenn : evil spirits in the oral cultural and popular Moroccan tradition.

- https://en.qantara.de/content/the-master-musicians-of-joujouka-the-faded-myth-of-the-goat-god

- Ghayta, air musical instrument. Player usually called ghayat.

- Cf. S. Davis. Jajouka Rolling Stone : a Fable of Gods and Heroes. New York : Random House, 1993. In this novel, the writer narrates the visit of a National Geographic journalist to Jahjouka and his efforts to publish an article on their music and their way of living. He, also, talks of the development of the group’s international career: visit of Brian Jones, recording with Randy Weston. He, also, covers the musical and theatrical tradition of Jahjouka. The book deals with the boujloudya celebration and its meaning, the royal decree officially establishing the group. He ends the work with interviews of multiples Jahjouka « movers » such as: Brion Gysin, William Burroughs, Paul Bowles, Keith Richards and Mick Jagger.

- https://greekgodsandgoddesses.net/gods/pan/

- Cf. R. williams. « Ornette and the Pipes of Jahjouka » in Melody Maker, March 17, 1973, p. 22.

- https://www.britannica.com/art/Beat-movement

- Cf. P. D. Schuyler. « The Master Musicians of Jahjouka » in Natural History 92 :10, pp. 60-69.

- https://breathing.com/blogs/breathing-methods-and-breathing-work/circular-breathing

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Circular_breathing

- Cf. K. Sabin. « Moroccan Music : The « Foreign » and the « Familiar » : an Annotated Bibliography and Discography », ( term paper for Popular Culture in the Middle East (SOCIO 470), Spring 2000.) http://users.ox.ac.uk/~sant1114/MoroccanMusic.htm #Jahjouka

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clash_of_Civilizations

- https://www.thoughtco.com/the-roman-festival-of-lupercalia-121029

- https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/a-rolling-stone-s-moroccan-odyssey-1.946158

- vv

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Master_Musicians_of_Joujouka

- https://www.moroccoworldnews.com/2013/03/84230/joujouka-masters-musicians-the-healing-power-of-a-4000-year-old-music/

- https://www.nytimes.com/1995/10/12/arts/the-pop-life-057142.html?mcubz=0

- With Sommerville, Gysin built the Dreamachine in 1961. Described as “the first art object to be seen with the eyes closed”,[13] the flicker device uses alpha waves in the 8-16 Hz range to produce a change of consciousness in receptive viewers.

- https://www.seattletimes.com/entertainment/master-musicians-of-jajouka-at-neumos/

- https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/a-rolling-stone-s-moroccan-odyssey-1.946158

- https://www.123helpme.com/hamlets-madness-in-craft-preview.asp?id=223930

Bibliography:

- Chtatou, Mohamed. 1986. « The Magical World of the Master Musicians of Jahjouka » in BRISMES Proceedings of the 1986 Conference on Middle Eastern Studies. Ed. L.D. Lanthan. Oxford : British Society of Middle Eastern Studies, 1986.

- Davis, Stephen (1993). Jajouka Rolling Stone: A Fable of Gods and Heroes. Random House.

- Gysin, Brion (1969), The Process. Doubleday

- Hamri, Mohamed (1975). Tales of Joujouka. Capra Press.

- Palmer, Robert (14 October 1971). “Jajouka: Up the Mountain,” in Rolling Stone, 14 October 1971.

- Schuyler, Philip (1992). « The Master Musicians of Jahjouka » in Natural History 92 :10, pp. 60-69

- Schuyler, Philip (2000) “Joujouka/Jajouka/Zahjoukah – Moroccan Music and Euro-American Imagination”, in Armbrust, Walter, editor. Mass Mediations: New Approaches to Popular Culture in the Middle East and Beyond. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

- Strauss, Neil (12 October 1995). “The Pop Life: To Save Jajouka, How About a Mercedes in the Village?” in The New York Times, 12 October 1995.

- Williams, R. (1973). « Ornette and the Pipes of Jahjouka » in Melody Maker, March 17, 1973, p. 22.

Discography

- Brian Jones Presents the Pipes of Pan at Joujouka (1971)

- Tribe Ahl Serif: Master Musicians Of Jajouka (1974), Musical Heritage Society MHS 3292/93

- Le Rif: La tribu Ahl Serif (credited to Maîtres musiciens de Jajouka; 1978), Arion ARN 33431

- Joujouka Black Eyes (1995)

- Moroccan Trance Music: Vol. 2: Sufi (featuring Gnoua Brotherhood of Marrakesh and The Master Musicians of Joujouka, 1996)

- 1O%: file under Burroughs own track plus separate collaborations with Marianne Faithfull, William Burroughs and Scanner.

- Boujeloud (2006)