The Atlantic

Dina Temple-Raston

“The women scholars here are even more important than men.”

Morocco is in a region vulnerable to terrorist recruitment, but it hasn’t had a significant attack on its own soil since 2011, when terrorists bombed a Marrakesh café. Yet ethnic Moroccans have been at the center of ISIS attacks in Europe. The only alleged survivor of the 2015 Paris rampage is a Frenchman of Moroccan origin; his trial began last week. The men behind the Brussels airport and tram bombings that happened months later were also ethnic Moroccans. The suspected driver of the van that mowed down shoppers in Barcelona was Moroccan-born.

Some 1,600 Moroccans are thought to have joined extremist groups, mainly ISIS, since 2012, with some 300 still fighting with ISIS, according to Moroccan Interior Ministry figures. Although these figures are low compared to, say, Tunisia’s—some 7,000 Tunisians joined the group over the same period—the death toll in Europe has brought into focus the need for prevention and Morocco has come to play an outsized role in the debate over how, exactly, young people can be stopped from embracing radical Islam.

It’s one of many countries around the world experimenting with various “countering violent extremism” (CVE) or de-radicalization programs. As Maddy Crowell noted in The Atlantic, “Germany, Britain, and Belgium have developed programs that focus on further integrating radicals into their community. Saudi Arabia, on the other hand, focuses on finding jobs and wives for recruited jihadists.” But programs that reach people once they’ve already been radicalized might come too late. “The most effective kind of rehabilitation and reintegration is the rehab and reintegration that doesn’t have to happen, because the person was afforded an off-ramp before they got to the point of no return,” Nathan Sales, the coordinator for counterterrorism at the U.S. State Department, told me. “What does that look like? It looks like early intervention and not necessarily and maybe not ideally by government officials.”

Early intervention spearheaded by local community leaders and groups, as opposed to government officials, was a focus of America’s CVE approach under the Obama administration. “Community leaders, neighborhood leaders have a comparative advantage in a number of different dimensions,” Sales said. “They will know more than government officials will about problems that might be cropping up and they also have a way to intervene in a way government people wouldn’t be able to … to steer somebody who is at risk of taking a wrong path and bringing them back into the fold.” President Trump recently stripped fundingfrom several groups aiming to counter extremism through this kind of outreach. Meanwhile, Morocco has continued to invest in it. Through various experimental initiatives, the country is attempting to show how a certain kind of religious education can prevent extremism.

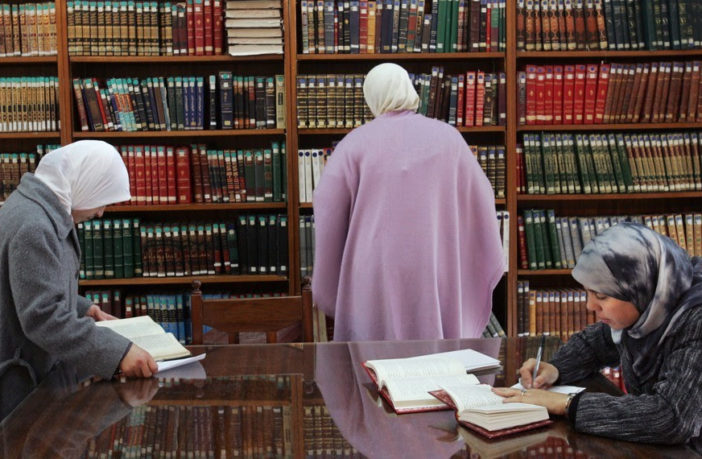

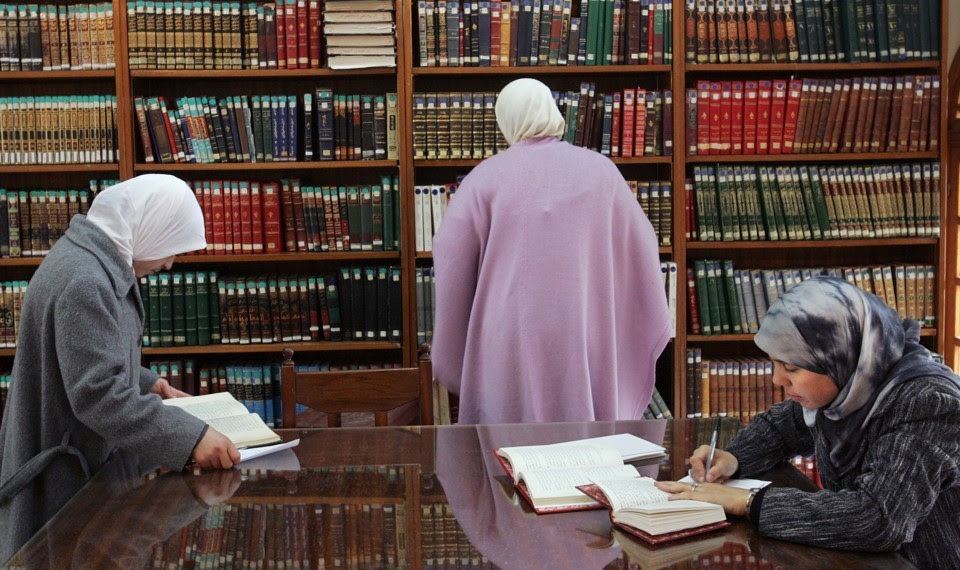

One particular initiative comes with a twist: It places a special emphasis on women. Eleven years ago, Rabat saw the opening of an elite new school called L’Institut Mohammed VI Pour La Formation Des Imams, Morchidines, et Morchidates. It turns young women into religious scholars and then sends them out into pockets of the country where radical Islamists are known to recruit disenfranchised youth—to provide spiritual guidance that contradicts the messages they might receive from violent extremists. Making school visits and home visits, each woman—called a morchidat, or spiritual guide—talks to young Muslims and contests interpretations of the Quran that terrorist groups use for recruitment. For women to be employed by the government to do this kind of work within Morocco’s Islamic communities, where spiritual leadership is generally the domain of men, is unusual. Men are also trained at the Rabat school, but it’s the hundreds of female graduates who are having the most impact, according to the program director, Abdeslam El-Azaar.

“I’ll tell you frankly, the women scholars here are even more important than men,” said El-Azaar, a thin grandfatherly man in a cream-colored Moroccan tunic and a burgundy fez. “Women, just by virtue of their role in society, have so much contact with the people—children, young people, other women, even men. … They are the primary educators of their children. So it is natural for them to provide advice,” he said. “We give them an education so they can offer it in a scholarly way.”

The morchidat program leverages a woman’s familial and social influence to combat radical Islam at the level of the sidewalks—and at individual mosques. “We’ve found over the years that if we have women organize something at the mosque, 450 people show up. If the men are put in charge, they’re lucky if 25 guys make the effort,” El-Azaar said.

Zineb Hidra, a morchidat whose cherubic face and tortoiseshell glasses make her look much younger than her 49 years, was in the first graduating class of women 11 years ago. Since then, she has been working as a full-time employee of the Ministry of Islamic Affairs in the inner-city neighborhoods of Casablanca. “It was hard at first,” Hidra told me. “People didn’t trust us. … They’d never seen anything like that before.”

One afternoon in 2006, Hidra was rushing down a middle-school corridor when six students and their teacher barreled out of a classroom into the hall. The teenagers wore robes and billowy izaar pants that hit above their ankles—the supposed style of the Prophet Mohammed—and they stood in a circle berating their teacher. His history lesson, they said, was blasphemous, contradicting the words of the Prophet. Hidra felt her heart begin to race. “These were exactly the signs we were told to look for—how they dressed, how they acted at school, and how they talked about religion,” she told me later. “It was clear they had picked up ideas about Islam that were taking them down the wrong path.” Hidra asked them if she could help. It was, she recalled with a smile, her very first radicalization case.

As Hidra continued her work in Casablanca, she faced resistance. When she went to call on mothers in their homes, knocks went unanswered, even though “we knew people were inside,” she said. Local women avoided her at the mosque. Even school administrators wondered what she was doing in the hallways, concerned that if she found radicalized youth among the student body then the schools themselves would suffer.

Hidra said it required quiet patience to earn their trust. “As they saw more and more of us, we became easier to accept,” she explained, and people in the community began asking her for advice or suggesting she go talk to this young man or that family where a problem with radical ideas might be developing. “It probably helped that we didn’t argue with [the young people we talked to],” she said. “We just answered their questions. We helped their families. We sat with the mothers and taught them how to help their children.”

Many of the young Moroccan men and women who turn to groups like ISIS feel isolated, come from violent homes, or have been involved with petty crime. Radical Islamists offer them community and tell them that a full-throated embrace of their religion—an embrace that includes violence against nonbelievers—is the solution. Morchidats like Hidra suggest the solution is less doctrinaire. They walk young people through Quranic passages that emphasize tolerance, and provide gentler interpretations of passages that could be taken to promote violence. The idea is that young people eventually learn that their faith is not at odds with their families or society more broadly, and that this provides a lasting bulwark against terrorist recruiters.

L’Institute Mohamed VI sits in a neighborhood that feels more southern California chic than North African Maghreb. The school is surrounded by white stucco houses and colorful explosions of bougainvillea. The campus itself is hidden behind a succession of wrought iron gates; security is tight, as many Islamists don’t approve of their moderate teachings.

Admission is highly competitive. Students apply from all over the Arab world and Africa; only about 10 percent are accepted. To be eligible, students must have already completed an undergraduate degree and be in good standing in their communities—without, for example, a criminal record. Successful women candidates must have committed half the Quran to memory before they arrive; men, many of whom will go on to become imams, must have it memorized in its entirety. This is an important requirement because it typically takes years to memorize the Quran, and if incoming students are already deeply familiar with the texts, the center can focus on interpretation instead of memorization.

Once enrolled, students pay nothing. The Moroccan government picks up the tab for tuition, room and board, books, medical care, flights home, and small monthly stipends.

Of the roughly 250 new students accepted each year, nearly half are women. There is no strict segregation of the sexes, but there is separation. Men and women attend classes together in the same modern lecture hall, and women fill the last 10 rows in the back. Even from their separate perch in the hall, they offer a visual representation of progress. (Often, in devout Muslim-majority countries, men and women are educated in separate classrooms.)

The program has two tracks: One for Moroccan students and another for foreigners. Moroccan candidates study at the center for 12 months, 30 hours a week. The foreign students are placed in a two- or three-year program, depending on their Arabic language proficiency, and then grouped by country so they can receive specific instruction in their nation’s laws, rules of civil society, geography, and history. The goal is to create not just an Islamic scholar, but a respected intellectual who can answer a variety of questions, El-Azaar explained.

Morocco may be perfectly positioned to offer this kind of instruction. Its monarch, King Mohammed VI, is believed to be a direct descendant of the Prophet Mohammed. Constitutionally, he is considered the Amir al-Mu’minin, or Commander of the Faithful, which gives him both religious and political authority over the Moroccan people, 98 percent of whom are Sunni Muslim.

“In recent years, we’ve relied on the military to combat terrorism on its own,” El-Azaar told me, referring to the nation’s beefed up intelligence and security forces. “Now we’re fighting this on two fronts—the military and the ideological,” he said. “We’ve found over the past ten years that women are uniquely placed to spread moderate messages in a way that imams and fathers can’t, and we’re focusing on that.”

How effective the morchidat program is at preventing young people from joining groups like ISIS is difficult to quantify. While the women undoubtedly have helped young people with questions about their religion, it’s impossible to know how many of those youth might have become radicalized enough to join a terrorist group or launch an attack if not for the presence of the morchidat. The program is also only 11 years old—not long enough to meaningfully measure the success of such an initiative.

For the women in the program, however, there’s a side benefit that they find indisputable: It has elevated their status as women in society. Faitha El-Phammouti, 25, is in the class of scholars graduating later this year. She says the whole experience hasn’t just changed the way other people look at her, it has changed the way she sees herself. “I used to think men were superior to women,” she told me. “Now I don’t just think we’re equals, I think women come out ahead. We aren’t forced to work; we have a lot of autonomy and as morchidats we can have a profound impact on society, even more than men can, because we can talk to the young people and explain to them about the true Islam and they are willing to learn from us.”

El-Phammouti seemed unbothered by the possibility that it does not really change the role of women in society, because women at the institute are not permitted to follow a more rigorous course of study and become imams—that job is still reserved for men. Of the program, she said simply, “It’s very exciting.”

And what of those six radicalized students Hidra met years ago in a middle school corridor? She ended up meeting with them three times a week for six months. “Our religion tells us to be patient and insistent and that’s what I was,” she told me. “They asked questions and I gave them answers, guiding them to the right path. It took a long time, but slowly they started changing their clothes and started looking like the rest of the kids. They began engaging in school and stopped challenging their parents. Eventually they got to the right place.”

Today, all six of the young men have jobs. Three have graduated from college. One happily announced to Hidra that he’d just passed the officer’s exam for the police. He didn’t want to talk about what had happened in middle school—he had put those kinds of “foolish ideas,” he said, behind him.