By Graham Cornwell

SMITHSONIANMAG.COM

Confederate agents seeking European support were imprisoned by the U.S. consul, which ignited international protest.

n the winter of 1862, Union troops occupied Fort Henry and Fort Donelson on the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers. Jefferson Davis was inaugurated as President of the Confederacy. Two ironside battleships, the Monitor and the Merrimack fought to a stalemate off Hampton Roads, Virginia. And on the coast of North Africa, 40 U.S. Marines landed in Tangier, Morocco, to help quell a riot and take possession of two Confederates who had been arrested by the U.S. Consul.

This bizarre Civil War episode came about mainly because of the infamous exploits of the C.S.S. Sumter, a Confederate blockade runner commanded by Raphael Semmes that had been terrorizing the U.S. Navy and Northern merchants throughout the Atlantic. On January 18, 1862, the Sumter docked in Gibraltar in need of fuel and repairs. Through clever persistence, the U.S. consul in Gibraltar, Horatio Sprague, had successfully kept the Sumter there by pressuring the town’s merchants to refuse the Confederates all necessary supplies. Without coal, they were stuck.

Across the Strait of Gibraltar in Tangier resided the U.S. consul to Morocco, James DeLong, himself a former judge from Ohio and abolitionist who freed two slaves traveling through his jurisdiction in 1854. Prior to his posting, DeLong had never left the country; he knew little of diplomacy and nothing of Morocco. Upon arrival, DeLong had pledged to fight Confederates wherever he encountered them, to which his colleagues in the consular corps had politely informed him that he would have little chance to do so in Tangier.

DeLong had been in the job for one month when, on February 19, two Confederate rebels, the Sumter’s paymaster, Henry Myers, and Thomas Tunstall, the former U.S. Consul to Cadiz, Spain, arrived in Morocco on a French ship en route to Cadiz. Once DeLong caught wind of their arrival, he moved quickly to hire a cadre of Moroccan soldiers, arrest the Confederates, and lock them in chains in the Legation, a mansion gifted to the U.S. by the Moroccan sultan in 1821. The controversy that ensued offers a compelling snapshot of how diplomacy, commerce and imperialism all intersected as the U.S. and the Confederacy jockeyed for support abroad.

Tunstall, an Alabama native, had been U.S. Consul in Cadiz, Spain before the war and was removed by Lincoln because of his strong Confederate sympathies. Myers was a Georgia native who had resigned from the U.S. Navy after his home state’s secession from the Union in January 1861. Tunstall had not been aboard the Sumter, but met Semmes in Gibraltar and agreed to use his local connections in the ports of the western Mediterranean to help get the ship back out to sea.

Tunstall was known in the region’s social and political circles from his public service before the war. The European community in Tangier was broadly sympathetic to the Confederate cause. They were primarily merchants, and by 1862, they had begun to feel the initial effects of rising cotton prices. (Textiles made from the plant were the most significant import at the time in Morocco.) Estimates vary, but when news of DeLong’s actions spread, a few hundred people—mainly European—gathered in the streets, chanting and beating at the door of the Legation with the demand to release the two prisoners. DeLong refused, but would need the assistance of the U.S. navy to help push back the mob.

The “riot” eventually died down, but the controversy did not. DeLong wrote angry, accusatory letters to his fellow European consuls and diplomats, while they questioned the right of the U.S. consul to make an arrest on Moroccan soil. At the time, Morocco was in the midst of a major transition. A devastating military loss to Spain in 1859-60 had forced the makhzen (the Moroccan state apparatus under the ‘Alawite sultan) to accept greater European influence in commercial and political affairs.

European powers including France, Spain and England demanded the right to legal “protections” for their own citizens, and the right to extend those protections to Moroccans who worked for their respective consulates. In practice, these protégés, as they were known, often included the extended families of consular staff and important business associates. As protégés, they were no longer subject to Moroccan law or taxes. This allowed foreign powers to have an influence far beyond the relatively small size of their expatriate population (roughly 1,500 total) in Moroccan coastal cities.

Echoes of the Trent Affair from just a few months prior reverberated throughout the Tangier episode. In November 1861, the U.S. Navy stopped the British ship RMS Trent off the Bahamas and took two Confederate diplomats as contraband of war. British officials were outraged at the violation of their neutrality, and eventually the U.S. released the Confederates.

Those sympathetic to the Confederacy sought to draw a parallel between the incidents, but in reality, the Tangier arrests took place under very different circumstances. France made the somewhat dubious claim that, as passengers on a French ship, Myers and Tunstall were entitled to French protection. By disembarking and taking a stroll into town, the U.S. argued, the prisoners forfeited this protection. Furthermore, the U.S. maintained that the pair were rebels in the act of committing treason, and that American consular privileges allowed DeLong to arrest American citizens under American law.

The argument had merits, but DeLong lacked the diplomatic skills to advocate for his position. Delong was incredulous that Secretary of State William Seward offered only measured defense of his actions, not knowing that Seward’s later responses to French complaints made the case for the legality of the arrest. DeLong truly believed an orchestrated, anti-Union conspiracy was afoot among the Europeans in Tangier. His reprimand to his colleagues in the consular corps offended virtually everyone and the complaints began to pour in to Washington from other foreign ministries. With pressure coming from the Tangier’s most influential foreign residents, Moroccan officials ordered the prisoners to be released. DeLong steadfastly refused.

Meanwhile, the U.S. navy had several vessels patrolling the Strait of Gibraltar in search of the Sumter and other blockade runners. DeLong sent for help, and the U.S.S. Ino landed in Tangier on February 26, one week after the prisoners were first detained. Forty or so Marines marched up the tall slope to the Legation, took custody of Myers and Tunstall, and escorted them back to the ship. They were eventually taken to a military prison in Massachusetts, and then later released as part of a prisoner exchange. Moroccan officials put up no resistance whatsoever, despite their earlier requests to DeLong.

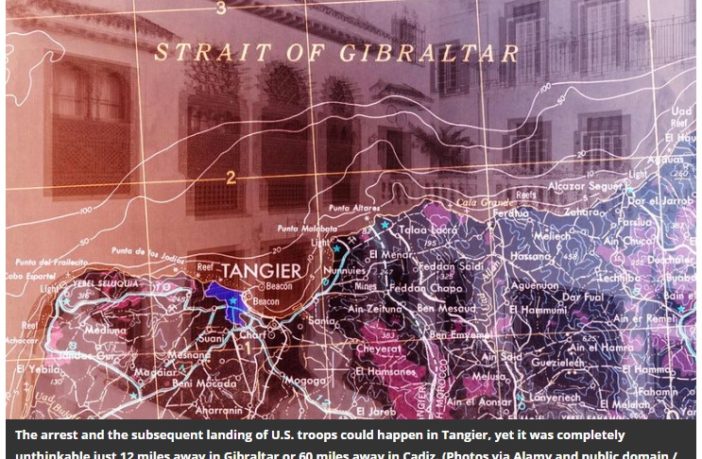

What are we to take away, exactly, from this brief moment of international intrigue? In short, Morocco’s unique and marginal position among the community of nations meant that foreign powers could take extraordinary actions there, but it also meant that Morocco was not subject to international legal norms. The arrest and the subsequent landing of U.S. troops could happen in Tangier, yet it was completely unthinkable just 12 miles away in Gibraltar or 60 miles away in Cadiz.

While we cannot say that Morocco was on the verge of being colonized in 1862, European powers were certainly interested in doing so. Neighboring Algeria had come under French rule in 1830, and Spain’s military campaign in northern Morocco in 1860 was an attempt to strengthen its position in North Africa. The British had just five years prior orchestrated a “most favored nation” trade agreement that dramatically liberalized commerce between Morocco and Britain—and later most other European trading partners. In the four years leading up to 1862, cotton textiles, tea, sugar and Manchester silverware all began to flow into Morocco in unprecedented quantities. European powers were flexing their muscles in Morocco, not just toward the sultan but toward their imperial rivals as well.

Morocco’s weakened and marginalized status meant that it had limited capacity to resist these incursions. Consuls declaring the legal right to arrest one of their own subjects—or to demand the release of a subject arrested by the makhzen—was a normal occurrence in 1860s Tangier. Likewise, Moroccan officials were not as in tune with the latest developments of the Civil War as their counterparts in Europe would have been.

In Gibraltar, for instance, DeLong’s counterpart, Sprague, had much less leeway in which to maneuver, but he could nonetheless apply diplomatic pressure to merchants and local authorities to isolate the Sumter. Without access to fuel and hemmed in by several U.S. cruisers, Semmes was eventually forced to pay off his crew and sell the Sumter. He departed for England where he took command of a new ship secretly built in Liverpool.

Where European powers maintained neutrality during the Civil War as a way of hedging their bets, Morocco had little need. After briefly wavering in the face of European protests, they sided with DeLong and the United States. When DeLong described Myers and Tunstall as treasonous rebels, Mohammed Bargach, the Moroccan niyab (or foreign minister) appears to have taken him at his word. Bargach likewise determined that the two Confederates were rebellious American citizens rather than wartime belligerents, and thus DeLong had every right to arrest them.

The Moroccan government later wrote to Washington to emphasize its friendship and willingness to side with the United States against the rebels. They vowed to prohibit all Confederate ships from docking in Moroccan ports and promised to arrest any rebel agents who made themselves known in Moroccan soil. Although such a situation was somewhat unlikely, it was a bold declaration of U.S.-Moroccan friendship.

The little known “Tangier difficulty” or the “DeLong affair” was short-lived. DeLong achieved his goal—defending the Union on the other side of the Atlantic—but the diplomatic headache was not worth it for President Lincoln and Secretary of State Seward. DeLong was recalled after only five months on the job, and his nomination withdrawn from consideration in the Senate. The episode marked the only time Union troops were deployed outside the Americas during the war, and it marked just one of two U.S. troop landings in Africa in the 19th century.