Al Monitor

Fiercely autonomous Algeria is on a mission to cement US ties as regional tensions rise and oil revenues crash.

The North African giant needs Washington’s help to shore up a fledgling political settlement in war-torn Libya while preventing a simmering conflict in the Western Sahara from flaring up. At the same time, the country is working overtime to convince US companies of its potential as a stable, profitable destination for their investments.

“What we are asking the United States is how to make sure that the American business community — American companies — do have their share of the opportunities offered by Algeria,” Ambassador to Washington Madjid Bouguerra told Al-Monitor in a June interview at his Washington office. “The doors are open to them, in many sectors.”

The ambassador, in post for 18 months, is intent on demystifying a country that still bears the scars of a brutal war of independence followed by an Islamist uprising in the 1990s. While US ties date back to the 1795 Treaty of Peace and Amity, they remain delicate due to Algeria’s Cold War-era ties to Russia and lingering tensions with US ally Morocco.

Several bilateral mechanisms have been established in recent years to try to put the relationship on firmer footing. These include both strategic and military dialogues, as well as a trade forum.

Like many other countries across the region, Algeria has been walloped by the global oil glut. Trade between the two countries is down from $24 billion in 2012 to just $7 billion last year, Bougherra said, largely due to the United States’ increased self-sufficiency in oil and gas.

“Economically we used to have much stronger relations when the United States was importing oil and gas from Algeria,” he said. “Unfortunately, that’s not anymore the case since last year.”

Algeria, like other resource-rich countries, hopes to create a post-oil economy for its large youth population, notably in the automative, agricultural and pharmaceutical sectors. Bougherra in particular hailed Algeria’s recent constitutional reforms.

Algeria is also making an impression on the regional stage, where it has long argued for local solutions and against foreign interference. Algiers was notably an early proponent for the creation of a Government of National Accord in neighboring Libya, an idea now endorsed by the international community, including the United States.

“It is our duty as partners and friends of Libya to help the GNA form a national army and a national security aparatus,” Bouguerra said. And if other Libyan factions still won’t get on board, he said, maybe it’s time for a little “diplomatic pressure.” “Some are talking about sanctions,” he said. “I don’t know if that’s going to work, but if that can help, why not?”

“It is our duty as partners and friends of Libya to help the GNA form a national army and a national security aparatus,” Bouguerra said. And if other Libyan factions still won’t get on board, he said, maybe it’s time for a little “diplomatic pressure.” “Some are talking about sanctions,” he said. “I don’t know if that’s going to work, but if that can help, why not?”

Even as a political settlement in Tripoli sparks hope for a resolution to the five-year-old conflict in Libya and a unified front against the Islamic State (IS), a much older conflict may reignite on Algeria’s western flank.

Western Sahara activists, many of whom live in Algerian refugee camps in Tindouf, are increasingly talking about picking up arms against Morocco as a 25-year UN initiative fails to deliver a promised referendum on independence for the contested territory.

Bougherra said he understands their frustration. He said the UN must reconstitute its Western Sahara mission expelled by Morocco in March if conflict is to be avoided.

“The credibility of the Security Council is at stake, really. But also the future of the UN peace missions,” he said. “If Morocco can [kick out the UN] today, other countries will do it tomorrow.”

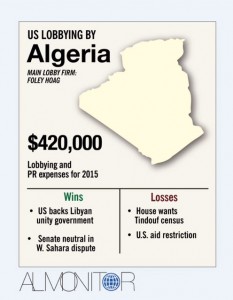

To help get its point of view across on the Sahara, Algeria for the past decade has relied on US lobby shop Foley Hoag. The $420,000 annual contract for two lobbyists, however, is dwarfed by Morocco, which spends almost 10 times that amount to convince US policymakers that any alternative to its proposal for autonomy under Moroccan sovereignty will only lead to chaos.

House appropriators this year included a Moroccan-backed proposal in their proposed foreign aid spending bill to pressure Algiers to allow a UN census of the Tindouf camps, prompting an angry response from Bouguerra. Senators have been far friendlier to Algiers: Their foreign aid bill makes no mention of a census, but rather awards Algeria $1.4 million in counterterrrorism training — $100,000 more than President Barack Obama’s request — in recognition of “the contributions of Algeria to countering extremism in the region.”

Another persistent source of acrimony has been Algeria’s dismal standing in the State Department’s annual Trafficking in Persons report. The latest report, released in late June, ranks Algeria in the bottom tier for the sixth year in a row, a public black eye that also makes the country ineligible for many forms of aid.

“The government of Algeria does not fully meet the minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking and is not making significant efforts to do so,” the 2016 report states. “The government newly acknowledged the trafficking problem in Algeria and demonstrated new political will to address it. It formed an inter-ministerial anti-trafficking committee, which produced a national anti-trafficking action plan in December 2015; however, the government did not dedicate a budget to implement the plan during the reporting period.”

Bouguerra said his oil-rich country doesn’t seek out US assistance and downplayed the State Department’s relatively tiny proposed aid package for FY 2017 — $2.3 million in security assistance, about the same as last year — as “very symbolic.” But the ranking clearly rankles.

Records show Foley Hoag has actively lobbied the State Department’s human rights bureau, which helps put the rankings together. In December, the firm sat on a conference with Susan Coppedge less than two months into her tenure as the department’s new ambassador-at-large to monitor and combat trafficking in persons.

Finally, Bouguerra concedes to being “a little bit disappointed” by the impression that President Abdelaziz Bouteflika is subject to a constant deathwatch in foreign capitals.

The 79-year-old president’s re-election to a fourth five-year term in 2014 “underscored Algeria’s political continuity, while focusing attention on succession issues,” the Congressional Research Service wrote in a 2014 report to US lawmakers and their staffs. “Algeria’s factionalized and opaque decision-making process often appears to inhibit a clear trajectory on political and economic reforms, as well as a more proactive Algerian foreign policy.”

The ambassador insists that Bouteflika will stay in office through the end of his fourth term in 2019. He rejected rumors to the contrary as media fabrications in France, Algeria’s former colonial master.

“People here need to be smarter than that and see that in Algeria, they have a man who is in command,” Bouguerra said. “The president for the past 15 years has built an Algeria which really will stand up by itself, not by the will of one man. At least in Algeria, nobody is afraid of what will come after 2019. It is a strong and reliable ally, really.”

Julian Pecquet is Al-Monitor’s congressional correspondent. He previously led The Hill’s Global Affairs blog. On Twitter: @congresspulse Contact him via email jpecquet@al-monitor.com

JULIAN PECQUET

Congressional Correspondent