Newsbook

By Gordon Watson

The migration data collection and analysis organisation, Xchange.org, today publishes its latest survey exploring the major migration transit hub of Agadez, Niger.

This is the first in a two part series looking into the mixed migration flows across the African continent and using the first-hand accounts of people transiting through the route.

The report expands the previous, ‘Central Mediterranean Survey’, delving deeper into the experiences of African migrants using the migration hub and the consequences of the criminalisation of the route since 2015.

Perception and reality

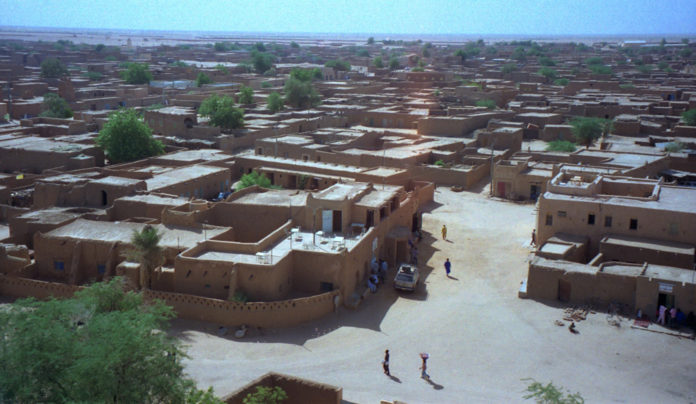

The dusty city of Agadez has always been a key trading spot in Sub-Saharan Africa and the last oasis before the hazardous and unforgiving Saharan desert to its north. It was also once a vibrant tourist hub with direct flights from France bringing tourists keen to visit the sun-dried mud homes, its Tuareg culture and the famous Grande Mosquée d’Agadez, built in the 1500s.

As the tourism industry waned and the Tuareg rebellions erupted just over a decade ago, the city and its people have had to rely on new forms of livelihoods to support them. Many transferred their trade skills and tourism focus towards the assistance and transportation of African migrants coming from across the Western side of the continent and heading north to Libya and Europe.

According to Xchange’s previous survey just over half of those asked had transited through Agadez. It featured as one of the last urban zones before the journey across the desert. The analysis also found the Niger was the second most dangerous route taken by its mostly young male respondents. The team recorded 32 incidents during the course of transit; which included Arrest/Detention, Extortion, Kidnapping and Physical Abuse.

‘In the desert near Agadez, Tuareg transport people… rob their money, beat and abandon them in the desert’, a Guinean migrant describes of their treatment by smugglers in Agadez.

Although the demand for transit north has led to a growing business of people smuggling, the numbers do not reflect a wave of mass migration. Figures suggest instead that less than 9% of migrants in Europe were coming from Sub-Saharan African and 1.7% of those coming from Sub-Sahelan Africa are immigrants (as of 2017). Compared to the migration phenomenon portrayed in the media this is often better understood as a culture of migration across the region.

Tip of the Iceberg

So far this year, over 200 people have lost their lives crossing the Central Mediterranean. This human tragedy continually grips the media’s attention over on-going arguments towards creating an EU solution to manage flows of migrants rescued by civil society NGOs. While the numbers of people dying in the Mediterranean are tragic, there is an understanding that these could be far outweighed by those who die on the journey to Libya.

According to a new study by the International Organisation for Migration, released in December last year, it was found that over 6,600 Africans were reported to have died in the last five years attempting to cross the Sahara Desert. The study calls this number of deaths, ‘just the tip of the iceberg’.

Adding eyewitness accounts of deaths witnessed during 2018, IOM was able to confirm that around 1,400 migrants perished making the journey. Still, this number reflects only the ones that are known about.

The journey, as we know it

Understanding people’s motivations to make the journey and how their journey unfolds, are still a developing picture.

During an episode of the MOAS podcast entitled ‘Crossing the Desert’, Petra Suric Jankov of the Catholic Relief Services described the process from Agadez.

‘Typically, what we’ve heard is happening is there’s a couple, one or two success stories of someone in their community or in their family that has made it across and has made it to Europe, they provide hope to those left behind. And people decide that they have no other options and they attempt to go on this long journey across West Africa, they pool money, all their life savings and their family contributions and they take everything that own in their pockets to go for this one agenda, making it to Europe to make money to feed their families back home. Many say that their ultimate goal isn’t to stay in Europe, it is to provide for their families and eventually return to their countries and continue to help the development there.

So when they start on this journey, they travel across West Africa pretty freely, there’s a very open flow of movement in West Africa thanks to the ECOWAS protocol where migrants in West African countries, they can easily enter and cross borders without visas. So Agadez is one of those last points in West Africa where migrants when they arrive they’re still legal, it was an easy route up until that point. It’s once they arrive in Agadez that things become more complicated, it’s when they have to start paying off the smugglers and the truck drivers and the people who tell them ‘we know the best route’ and they have to find lodging. That’s when most end up losing all the money that they have once they get to Agadez. Some stay, try to stay long enough to make more money, some have just enough left to make the promise of being transported across the desert.

Then what typically happens and what we’ve heard from many of the migrants who have attempted the crossing and failed is they’ll say half way through the desert they’ll get dropped off the truck and say ‘give us more money or we’ll leave you here’ and they do and they leave them and they have to find and fend for themselves or they get to Libya and they’re in a stateless situation and they have very few networks there. So they’re trying to connect to what they’ve heard through the grapevine but if any point in the transit gets broken if there’s any link that gets miscalculated, they’re left on their own and that’s when the dangers become extraneous. They try to find their way back, they get lost in the desert, many perish. But those who do find their way back always say, I wish I knew and if I knew now what I knew then I would’ve never ever tried.’

Speaking to the Voice of America, IOM’s spokesperson, Joel Millman, said that smugglers and traffickers take advantage of those making the journey and they are powerless to stand up for themselves.

‘Starvation, dehydration, physical abuse, sickness and lack of access to medicines are causes of death frequently cited by the migrants who reported deaths on routes within Africa, …

Involvement with human smugglers and traffickers in human beings can put people in extremely risky situations in which they have little agency to protect themselves, let alone fellow travelers they see being abused.’

A crackdown

The Nigerien government introduced new legislation criminalizing people smuggling from Niger in August 2015. Under Law 36, smugglers and migrants would arrested if caught in the act. This would be accompanied by greater monitoring of Niger’s Northern border to prevent trucks of migrants from departing.

In almost two years, there had been an 80% reduction in the number of illegal migrants transiting through the city, something the city’s governor Sadou Soloké praises.

But, these measures have resulted in the creation of ghettos across the city and the forcing underground of the smuggling industry.

The ghettos are described to be overcrowded with migrants from across the continent, living in conditions without electricity, water or access to enough food.

In the efforts to escape north, these migrants are now left in a limbo, trying to escape poverty and yet left living in dire conditions.

The interest from Xchange’s latest report will be to understand what these men explain about their current lives in Agadez and from those who have made the journey, if the risk is really worth the reward.