By Stylianos Kostas

Political Scientist

Morocco, historically known as a country of emigration, is also an important crossing point for migrants, mainly from Sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, with Europe being a common destination for both migration flows. However, since the mid-1990s, and especially the latter part of the decade, Morocco has become a destination country as well. The reasons for these migration flows range from political unrest, civil war, and economic downturns in some West African countries to the eruption of ethnic violence and mass deportation of immigrants in Libya in 2000, where many Sub-Saharan immigrants had previously found opportunities to work.[1] As a result, Morocco today occupies three roles within the Euro-African migration system — that of a source, transit, and final destination country.

During the past few decades, the subject of Moroccan emigration to the Member States of the European Union (E.U.) monopolized the relevant debates on migration management at the national level. Indeed, mobility between Morocco and Europe has long been a vexed issue in their shared history. Moroccans residing abroad more than doubled from 1993 (1.5 million) to 2012 (3.4 million), with an average annual growth rate of 9.9 percent, compared to a 2.2 percent population growth rate in Morocco.[2] The vast majority emigrated to Europe (87 percent), with France alone hosting 31 percent,and Spain a quarter of these migrants.[3] The combined effects of family reunification, family formation, natural increase, undocumented migration, and new labor migration to southern Europe (and North America) explain why the number of Moroccans living in the main European receiving countries steadily increased.[4]

The surge in the number of Moroccan emigrants had a strong impact on the country’s relations with the E.U., and in particular with those Member States which received the majority of Moroccan irregular migrants,[5] namely France, the Netherlands, Belgium, Italy, and Spain. In 2014, among the top ten countries of origin of persons found to be unlawfully present on E.U. territory, Moroccans ranked fourth. That year, E.U. Member States determined in 30,920 cases involving Moroccan nationals that the individuals did not fulfil the conditions for entry, stay, or residence. Furthermore, of the top 10 countries of nationality refused entry to the E.U. in 2014, Morocco ranked ranked first, accounting for 65 percent (168,680) of the total.[6]

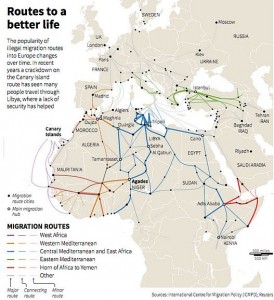

Beginning in the mid-1990s, the number of irregular migrants entering Morocco from Sub-Saharan Africa, and particularly from West Africa, increased. Most of these irregular migrants followed specific routes to Morocco, mainly via Mauritania or through Niger to the Algerian border near the town of Oujda (See Figure 1). The original intention of many of these new arrivals to Morocco was to continue their journey to Europe.[7] Those who managed to avoid arrest by Moroccan authorities usually made their way through the country to the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla, which, as extra-European territorial entities, constituted a possible alternative to the dangerous crossing of the Mediterranean in order to gain entry to E.U. territory.

Figure 1: Main migration routes to, through and from Morocco

Source: International Centre for Migration Policy and Reuters.com

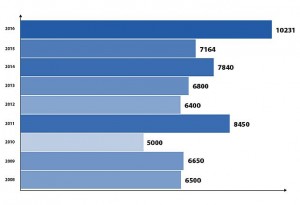

The number of irregular migrants using the western Mediterranean route, including Morocco with its two seacoasts, increased from 5,003 in 2010 to 10,231 in 2016.[8] (See Figure 2.) Morocco thus has emerged as a key migration transit country.[9]

Figure 2: Number of illegal border crossings on the Western Mediterranean route (sea and land)

Source: FRONTEX, http://frontex.europa.eu/trends-and-routes/western-mediterranean-route/.

However, a large number of the irregular migrants who arrive in Morocco do not complete their journey to Europe. Instead, many have to abort, or at least delay their attempt to reach Europe due to the intensified securitization policies implemented by Moroccan and Spanish border police. Major operations conducted by Moroccan authorities aimed at thwarting irregular migration resulted in 60,996 arrests in 2002 alone.[10] A little over a decade later, Morocco became the first Mediterranean country to sign a Mobility Partnership with the E.U., intended to promote a “global approach to migration and mobility” (i.e., essentially to “manage” irregular migration).[11]Nevertheless, Morocco has remained reluctant to readmit or expel unauthorized migrants en masse. Whereas efforts succeeded in curbing the influx of irregular migrants to Europe, they stranded many irregular immigrants in Morocco. Thus Morocco has emerged as a destination country.

The decision by irregular immigrants to remain in Morocco appears to be one forced upon them mainly because of their fear of the high probability of arrest either in Morocco or in Spain, which could then lead to their deportation to their country of origin. Additionally, it is often the case that irregular immigrants find themselves unable to meet the financial demands of human traffickers organizing their passage to Europe. In fact, the poorest among them are in the most vulnerable position. To them, remaining in Morocco, in spite of the difficulties they are likely to face, is preferable to returning their home countries.

The present political, economic, and social conditions in the Sub-Saharan region continue to motivate irregular migrants to Morocco. Estimates of the number of irregular migrants from the Sub-Saharan Africa residing in Morocco vary. Nevertheless, figures obtained from the regularization campaign of 2013 offer some indication of its scale: of the 27,332 applications filed, about 80 percent were identified as citizens of non-Arab African countries. [12] It is believed that the number of these irregular immigrants is likely to be higher and growing.[13]

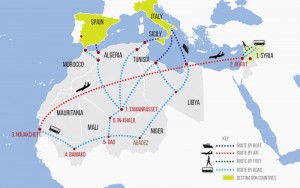

In addition to the large and growing influx of irregular migrants from Sub-Saharan Africa into Morocco, are refugees and asylum seekers fleeing the turmoil in the Middle East, particularly from Syria. Morocco today is perceived by immigrants and refugees as one of the few stable and secure countries in the region. Viewing their prospects for migration to Europe as having become much more difficult than other migratory routes, they have tended to use Morocco either as a transit or as a destination country (See Figure 3). While the over 6,000 refugees and asylum seekers in Morocco come from 49 countries, more than 60 percent of them are from the Syrian Arab Republic. Morocco has therefore become a destination country for refugees.[14]

Figure 3: The migratory route of Syrian refugees and asylum seekers to Morocco

Source: http://newirin.irinnews.org/global-refugee-crisis/.

Additionally, there is a large number of individuals who had previously arrived in Morocco in accordance with regular procedures, such as with student visas, short-term work permits, and as family members of Moroccan nationals. Most of these individuals, even if their permits have expired, remain in the country, thereby becoming irregular immigrants. As of September 2014, non-nationals in Morocco numbered 86,206, a marked increase from the 51,435 foreign nationals recorded in 2004, with one of the main reasons for this surge being irregular stay and work.[15]

The number of irregular migrants who, in recent decades, have arrived and eventually settled in Morocco, is significantly lower than that of the Moroccan nationals and others who, in the past, had attempted to irregularly cross the country’s borders in order to enter Europe. Nonetheless, taking note of the gradual increase in the number of irregular migrants who are arriving and residing in Morocco is important in understanding the country’s evolving migration profile. In turn, a more granular approach to Morocco’s complex and changing role as a source, transit, and destination country is essential to developing national policy responses.[16]

Indeed, there is a need for Morocco to address the phenomenon of irregular migration both systematically and humanely. Such an approach should aim not just at limiting the influx of irregular immigrants but also at managing-in the most appropriate way-the conditions of immigrants’ lawful entry and stay in the country, with a focus on their protection and ensuring their free access and exercise to fundamental rights. Morocco’s first law on irregular migration, Law 02-03, enacted in 2003, criminalized irregular migration, imposed strong sanctions for supporting and organizing it, increased border control capabilities, and set in motion regular raids of migrant settlements.[17] The next year, the U.N. Special Rapporteur on the human rights of migrants informed the Moroccan Government of concerns regarding the situation and living conditions of irregular immigrants, especially those originating from Sub-Saharan Africa.[18] Yet, despite these remonstrations and the work of Moroccan activists and international human rights NGOs who succeeded in bring to light the mistreatment of irregular migrants, the situation of irregular migrants in Morocco continued to fester.

In July 2013, Morocco’s National Human Rights Council issued a seminal report detailing a series of clashes between migrants and Moroccan police. The report prompted immediate instructions by King Mohammed VI to the government to develop a “a new vision for a national migration policy, that is humanist in its philosophy, responsible in its approach and pioneer at the regional level.”[19] As an initial step, the Moroccan government instituted a process for “regularizing” migrants’ status (i.e., provided legal residency status for at least 1 year) — a year-long, one-time process that ultimately granted this status to about 25,000 migrants. [20] However, Moroccan and international human rights organizations have continued to document the widespread ill-treatment of irregular migrants.[21] Meanwhile, in December 2016, Morocco launched a second regularization campaign; just three months into the implementation phase, the number of applications had already far exceeded expectations.[22] The fact that Morocco is now a country of destination does not differentiate its obligations in relation to the protection of immigrants’ rights; rather, it entails more responsibilities regarding irregular migrants residing in its territory. While Morocco has made some headway in assuming these responsibilities, it is clear that the country’s migration policy reforms are incomplete.[23]

Conclusion

The pattern of migration in the wider Mediterranean is complex and changing. The “push” and “pull” factors that propelled irregular migration in the past continue to be powerful forces driving many millions to undertake hazardous journeys today in search of personal safety and better lives. Morocco, which had long been a source country and more recently a transit country, has lately emerged as a destination country as well. Adjusting to these changing circumstances, and assuming the responsibilities that they entail, will require of Moroccan authorities a careful reassessment and further strengthening of national migration policies such that they both adhere to international human rights law and facilitate immigrants’ acceptance by local society. The emergence of a vibrant and capable civil society sector in Morocco that is committed to providing assistance and to advocating on behalf of migrants’ and refugees’ rights[24] is an encouraging development — one that might well lead to greater progress in Morocco’s efforts to reform migration policy in light of the country’s changing role in the Euro-African migration system.

[1] Özge Bilgili and Silja Weyel, “Migration in Morocco: History, Current Trends and Future Prospects,” Maastricht Graduate School of Governance, Migration and Development Country Profiles Paper Series (2009): 1-62, accessed March 22, 2017, https://mgsog.merit.unu.edu/ISacademie/docs/CR_morocco.pdf

[2] Migration Policy Center Team, “MPC – Migration Profile: Morocco,” Migration Policy Center – European University Institute Paper Series, Migration Profiles and Fact Sheets (2013): 1-8, accessed March 22, 2017, https:// http://www.migrationpolicycentre.eu/docs/migration_profiles/Morocco.pdf.

[3] Francoise De Bel-air, “Migration Profile: Morocco,” Migration Policy Center – European University Institute, Issue No. 5 (2016): 1-15, accessed March 22, 2017, https://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/41124/MPC_PB_2016_05.pdf?seq….

[4] Hein de Haas, “Country Profile: Morocco,” Focus Migration – Hamburg Institute of International Economics Paper Series, Country Profile No. 16 (2009): 1-11, accessed March 22, 2017, https://http://focus-migration.hwwi.de/uploads/tx_wilpubdb/CP_16_Morocco.pdf.

[5] There is no clear universally accepted definition of “irregular migration.” In this essay, the term refers to 1) foreign nationals without any legal resident status in the country in which they are residing, as well as persons violating the terms of their status so that their stay may be terminated; and 2) foreign nationals working in the “shadow “economy, including those with a regular residence status who work without registration to avoid taxes and regulations.

[6] European Parliament, “Irregular immigration in the EU: Facts and Figures,” European Parliament Publications, Briefing (2015): 1-4, accessed March 22, 2017, http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2015/554202/EPRS_BRI(2015)554202_EN.pdf.

[7] Özge Bilgili and Silja Weyel, “Migration in Morocco: History, Current Trends and Future Prospects.”

[8] Mehdi Lahlou, “Morocco’s Experience of Migration as a Sending, Transit and Receiving Country,” Istituto Affari Internazionali, Working Paper No. 15 (2015): 1-19, accessed March 22, 2017, https:// http://www.iai.it/sites/default/files/iaiwp1530.pdf.

[9] Michael Collyer, “States of insecurity: Consequences of Saharan transit migration,” Centre on Migration Policy and Society, University of Oxford, Working Paper No. 31 (2006): 1-32, accessed March 22, 2017, https:// https://www.compas.ox.ac.uk/media/WP-2006-031-Collyer_Saharan_Transit_Mi….

[10] Gabriela Rodríquez Pizarro, “Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights of Migrants: Migrant Workers, Visit to Morocco,” U. accessed March 22, 2017, N. Economic and Social Council – Commission on Human Rights, E/CN.4/2004/76/Add.3 (2004): 1-21, https:// https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G04/102/84/PDF/G0410284.pd….

[11] General Secretariat of the Council of Europe, “Joint declaration establishing a Mobility Partnership between the Kingdom of Morocco and the European Union and its Member States,” June 3, 2013, accessed March 21, 20017, https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-is-new/ne….

[12] Francoise De Bel-air, “Migration Profile: Morocco,” Migration Policy Center – European University Institute, Issue No. 5, (2016): 1-15, accessed March 22, 2017, https:// http://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/41124/MPC_PB_2016_05.pdf?sequ….

[13] Francoise De Bel-air, “Migration Profile: Morocco,” Migration Policy Center – European University Institute, Issue No. 5, (2016): 1-15, accessed March 22, 2017, https:// http://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/41124/MPC_PB_2016_05.pdf?sequ….

[14] United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (U.N.H.C.R.), “2017 Planning Summary: Operation Morocco,” Global Focus – U.N.H.C.R. (2017): 1-2, accessed March 22, 2017, http://reporting.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/pdfsummaries/GA2017-Moroc….

[15] Francoise De Bel-air, “Migration Profile: Morocco.”

[16] For an overview of Morocco’s legal framework for dealing with migration, see “MPC Migration Profile,” Migration Policy Centre (2013): 3-4, accessed March 21, 2017, http://www.migrationpolicycentre.eu/docs/migration_profiles/Morocco.pdf.

[17] See text of law (in French), http://www.consulat.ma/admin_files/Loi_02_031.pdf.

[18] Gabriela Rodríquez Pizarro, “Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights of Migrants: Migrant Workers, Visit to Morocco,” U.N. Economic and Social Council – Commission on Human Rights, E/CN.4/2004/76/Add.3 (2004): 1-21, accessed March 22, 2017, https:// https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G04/102/84/PDF/G0410284.pd….

[19] “Migration: Royal Instructions Bring a New Vision for a National and Humanist Migration Policy (Release),” Maroc.ma, September 12, 2013, accessed March 21, 2017, http://www.maroc.ma/en/news/migration-royal-instructions-bring-new-visio….

[20] See “Thematic Report on Situation of Migrants and Refugees in Morocco Foreigners and Human Rights in Morocco: For a Radically New Asylum and Migration Policy,” Kingdom of Morocco National Human Rights Council, accessed March 21, 2017, http://cndh.ma/sites/default/files/documents/CNDH_report_-_migration_in_….

[21] See, for example, “Expelled and Abused: Ill-Treatment of Sub-Saharan Africa Migrants in Morocco,” Human Rights Watch (2014), accessed March 21, 2017, https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/morocco0214_ForUpload_0.pdf.

[22] “Morocco to Launch Second Campaign of Illegal Immigrants Regularization,” Morocco World News, December 12, 2016, accessed March 21, 2017, https://www.moroccoworldnews.com/2016/12/203588/morocco-launch-second-campaign-illegal-immigrants-regularization/; and “Over 18,000 Sub-Saharans Seek to Regularize Their Immigration Status in Morocco, Morocco World News, March 9, 2017, accessed March 21, 2017, https://www.moroccoworldnews.com/2017/03/210567/over-18000-sub-saharans-….

[23] Katharina Natter, “Almost Home? Morocco’s Incomplete Migration Reforms,” World Politics Review, May 5, 2015, accessed March 17, 2017, http://www.worldpoliticsreview.com/articles/15691/almost-home-morocco-s-….

[24] Hein de Haas, “Morocco: Setting the Stage for Becoming a Migration Transition Country?” Migration Policy Institute, March 19, 2014, accessed March 21, 2017, http://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/morocco-setting-stage-becoming-mi….