By Francis Ghilès

for Barcelona Centre for International Affairs (CIDOB)

How can Morocco preserve its status as one of North Africa’s more prosperous and stable countries? Francis Ghilès believes that the country’s patronage system should be replaced by a more modern approach to decision-making – i.e., one that encourages greater social, economic and political dynamism.

This article was originally published in Issue 125 of CIDOB Notes Internacionals, a publication of the Barcelona Centre for International Affairs (CIDOB).

Morocco may never in its history been seen in more favourable light than now. Contrast helps of course. All around, while states have descended from uncertainty and civil strife into brutal civil war, Morocco stands out for its stability, economic growth and relative liberalism. It has weathered the fallout from the Arab revolts better than many Arab countries. Yet repression of the media and independent bloggers is greater today than before 2011. Nor is it easy to have a relatively open debate not least on economic issues.

In the 1970s, the longevity of its monarchical system was open to doubt after two attempts on the life of King Hassan II. In 1983, Morocco defaulted on its international debt, leaving the IMF to steer it through a structural adjustment process.

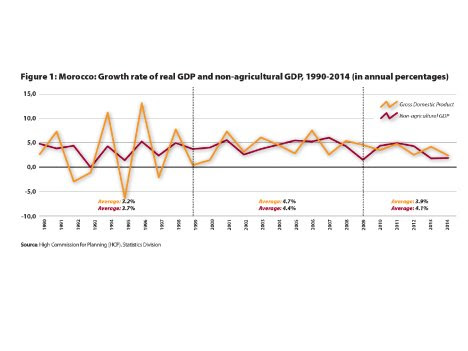

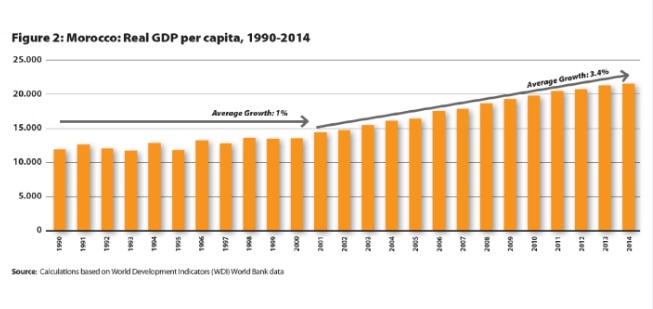

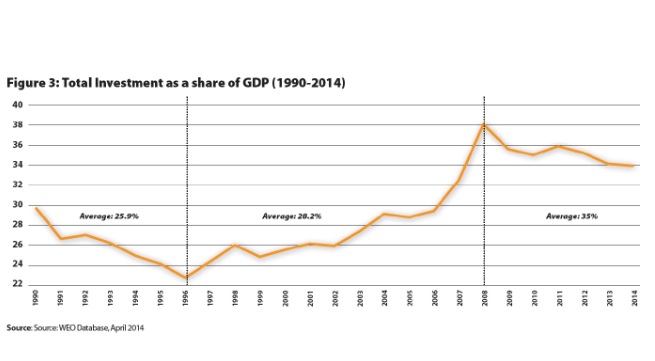

Since Mohammed VI succeeded his father in 1999, changes initiated before the turn of the century have taken their course. The country’s transport infrastructure has improved. Some of its major state and private companies have become more nimble international players than hitherto, helping to project the country’s influence into West Africa and beyond the southern Atlantic into Brazil. A new class of private entrepreneurs is shaking up what used to be a very complacent establishment. Foreign debt is now well below the levels of the 1990s. However internal government debt has increased, crowding out would be domestic borrowers. Average annual personal income reached $3.300. These encouraging trends are the direct result of the liberalising of the economy – not least in the all-important telecom sector with the huge success of the privatisation of the GSM in 1999 and modern regulation of this area of business which followed, and the kingdom integrating faster into world flows of trade and investment. Progress has been slowed since 2011 because of the consequences of the financial crisis after 2008.

Faster economic growth, a prerequisite to creating desperately needed new jobs, remains constrained by three factors which have not really changed over the years: a very low level of overall education hardly affects the yawning divide between a well educated elite and a third of all Moroccans who remain illiterate; an unreformed civil service – particularly at the local level, where average pay is low because the state seems incapable of offering good enough salaries to attract well trained people and a justice system which needs root and branch reform if corruption is to be brought under control; a relative lack of trust in the ability of a younger generation of Moroccan entrepreneurs to launch new companies and a consequent lack of financial support for them.

Existing rules of engagement are usually waived for major international investors such as Renault, Safran and Bombardier but that is hardly a special to Morocco. However, local talent, particularly when projects are small and medium size, often goes unnoticed and unrewarded. Too often, the state gives the impression it helps those entrepreneurs it wishes to, not necessarily those who are the most deserving of help. This patronage system must give way much faster to a more modern type of decision making if Morocco wishes to encourage the emergence of a strong autonomous private sector, likely to develop social, cultural and economic dynamism. That is why the system, though stable, still seems shaky.

The broader context

These challenges need to be set in the broader context of the ongoing debate about what is development. Until a generation ago, it was widely assumed among specialists that the best way to speed development was for countries to skip some of the process of modernization by copying those countries further along the path. Although discarded today, some projects in Morocco still operate on the premise that development can be accelerated by importing ‘best practise’ models from developed to developing countries. In the case of Morocco the model was, until a decade ago or so, France. That is changing fast as a new generation looks further afield and a more pragmatic Anglo-Saxon attitude takes root.

There are two main ways members of organisations can demonstrate their legitimacy. They can either appeal to demonstrable accomplishments such as their ability to fulfill their intended role in an effective manner or they can point at the fact that their organization looks like other similar institutions around the world, which are seen as legitimate, and claim that similarity makes their institutions legitimate by proxy. This second approach is known as ‘isomorphic mimicry’. The judicial system, the stock exchange and parts of the education system in Morocco have fallen into this trap. This creates a gap between visible institutions and the actors’ ethics in day to day affairs.

In Morocco, the monarchy carries considerable political and economic clout.

Mohammed VI is considered legitimate by most of his people. His situation is more comfortable than that of many of his peers in the region. The very centrality of the monarchy, which embodies both the deep and the ornamental state, as defined by the 19th century British constitutional writer Walter Bagehot, has a profound effect of the way the government and parliament function, indeed on the view the Moroccans have of themselves and foreigners have of Morocco. It influences the debates on the country’s future course. It sometimes stifles debate in the elite unless the king gives the lead: when that happens, the debate becomes legitimate.

When the monarch expresses no views, many Moroccans are most reluctant to express theirs. Nor are the king’s close advisers shy of using the weapon of lèse majesté when they want to avoid a debate or prevent one from going “too far”. Be that as it may, the monarchy’s role as a referee and driver of reform –or brake upon it- remains essential. The whole challenge lies in the ability of Moroccan rulers to dissociate monarchy as a stabilizing institution from the makhzen as source of bad governance and unfair policies. Morocco certainly is the darling of international lending agencies and of institutions such as the US Millennium Fund. This favour has as much to do with Western regional security concerns than with the country’s economic performance. Irrespective of its precise rate of growth or boldness in tackling economic reform, the kingdom retains precious support because it is perceived as an oasis of stability in a turbulent region.

Morocco has further burnished its reputation as a provider of security. This extends to religious security as it trains imams who return to their native West African francophone countries to preach a moderate version of the faith. Its security services are respected by their peers in the west though not always by ordinary Moroccans. This reputation underpins Morocco’s interests in the Western Sahara as few countries in the region wish to see any change in the status quo which has prevailed for four decades.

Infrastructure development

The development of motorways means that from Tangier in the north to Agadir in the south le Maroc utile as the French would put it has grown way beyond the 150 kilometres it occupied along the Atlantic coast between Kenitra and Casablanca twenty five years ago. This has encouraged private and public investment in a much broader geographical area than before. The railways have also been modernised. Critics however say that building a fast TGV train from Tangier to Casablanca is a misuse of scarce funds – a rich man’s toy and the result of undue French meddling. Equally important has been the creation of the intercontinental Tanger-Med port. This has given as a huge boost to the economy of Tangier, attracted large foreign investments such as Renault which will produce around 300,000 cars this year. Peugeot is following in Renault’s footsteps and will invest Euros 500 in a new car plant with the aim of producing 100,000 cars.

After independence in 1956, Morocco had turned its back on the Rif. The previous monarch had no liking for the region for deep seated historical reasons. His son has sought to reach out to what was traditionally a poor region which was not historically close to the Alaouite dynasty. A good road along the northern coast has the added advantage of opening up the country’s poor Mediterranean region and integrating its economy nationally.

The port of Casablanca, the country’s economic capital, is being modernised and developed. Further south, Safi and Jorf Lasfar are benefitting from the large increase in exports of phosphate rock and derivatives. A slurry pipeline has been operating for two months which carries the wet rock by tunnel from the phosphate mines in Khouribga to the export terminal at Jorf will have the further advantage of reducing pollution. As Morocco sits on an estimated 75% of world phosphate rock reserves, the growth potential of this region is huge. Other units in Jorf and Safi produce fertilizers. The development of such ports symbolise Morocco’s decision to develop export markets in Brazil and Africa. India however remains the phosphate company OCP Group’s main export market. A Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) terminal is being built at Jorf Lasfar. Morocco today imports all the gas it needs from neighbouring Algeria but the need to diversify suppliers was deemed strategically and economically important.

New economic horizons

Turning to Africa and Brazil has been viewed in Rabat as a strategic necessity insofar. As any hope that relations with oil and gas rich Algeria could improve has evaporated. The cost of closed frontiers in the Maghreb –at least two points of growth every year according to the IMF- is no longer a fashionable topic of debate. Trading with developing economies presents its own challenges. In the first quarter of 2015, emerging markets slumped to their weakest performance since the 2008-9 banking crisis. They no longer offer a dependable boost to world trade. The flood of money which made its way into emerging markets in the period of low interest rates that followed the crisis are slowing to a trickle if not reversing. The weakness of growth, if not the outright recession in countries such as Russia, Brazil, China and India has a greater global impact today than seven years ago. The contribution of these countries to growth, and particularly trade growth, outstripped their weight in the global economy. Thus, the BRICS accounted for 15% of world trade between 2000 and 2014, but contributed 23% of its growth during the same period. The loss of this outsized contribution is being keenly felt.

Moroccan exports to sub Saharan Africa are probably too small to be affected. It can be argued that the need to grow more food –the key reason for buying more phosphate rock and fertilizers- remains as great as ever. Furthermore a company like OCP Group is seeking to bring African producers of raw materials and feedstock together, bypassing the traditional role of Western companies in the value added chain: phosphates from Morocco, gas and potash from other African countries could be marshalled to manufacture fertilizers in Africa at an affordable price for local farmers. Fertilizer prices on the continent are among the highest in the world and, as a result, farmers use a fraction of what their peers elsewhere use. Meanwhile the percentage of arable land is declining while the population is surging.

Since 2006 OCP Group –formerly known as Office Chérifien des Phosphates- has undergone a managerial revolution – from a sleepy state company, 10% of whose employees worked out of a black glass clad headquarters in Casablanca to a more nimble international company able to raise $2.85bn worth of investment grade (-BBB) rated bonds in New York recently. Its CEO, Mustafa Terrab does not suffer from isomorphic mimicry. After acquiring a doctorate at MIT and he worked for that quintessentially American private company, Bechtel. That taught him modern management. OCP Group’s accounts are now audited and the company has rebuilt its operating method in order to ensure that production is more flexible than in the past and follows the needs of its international clients. It is no longer a question of simply producing as much rock as possible and getting the stuff onto the market at whatever price.

The proportion of fertilizers in the export mix has also progressed. In other words OCP Group is moving up the value chain. Beyond its traditional customers (India foremost among them) the company has made serious strides in Brazil. The country is one of the major producers of soy beans, corn, sugar and coffee in the world and offers plenty of opportunities to increase food production and processing. It also offers a good launching pad for trading and investing in other South American countries. Africa is the company’s other new frontier. Food production and processing may be more recession-proof than other sectors as world population continues to increase and millions of people are lifted out of dire poverty.

Banking is another sector where Morocco has come a long way since 1983. Its two leading banks, Banque Marocaine du Commerce Extérieur and Attijariwafa Bank, have built a network of banks in Western Europe and more recently in Africa. The team around Mohammed Kettani has turned Attijariwafa second name bank into a force for modernisation symbolised by its headquarters in Casablanca which house an important collection of modern Moroccan paintings. At BMCE, the man who spearheaded the group’s activities in Africa Mohammed Bennani has remained true to his initial conviction that private companies are key to shaping the new Morocco.

A younger generation of private entrepreneurs is following in the footsteps of their elders. They are also developing companies in sectors which no one would have dreamt of a few years ago. Outsourcia has developed in off-shoring and e-learning. Saham, which focuses on insurance, is now present in 28 countries in Africa and has stakes in hundreds of companies across the continent. Holmarcom is a force to be reckoned with in food processing, insurance and agriculture and has invested in Senegal. Anwar Invest for its part has built up an impressive portfolio in the food industry and cement.

Morocco faces three challenges

Of the three factors which act as a brake to a faster rate of economic growth in Morocco, two have been around for a long time, the third is more recent. The country’s elite is very well educated, many of the scions of senior civil service or private industrial families attending foreign secondary schools in Rabat and Casablanca and going on to elite schools in France and, increasingly, in the UK and the USA. The greater pragmatism of Anglo-Saxon ways of thinking and managing are increasingly in evidence at OCP Group and other major banks and companies but much less so in the civil service. Many Moroccan graduates choose to pursue international careers because they feel too constrained in their native country. The key point however is that overall the level of education of the mass of Moroccans remains very poor. This challenge is as old as independence but an unwillingness to confront the consequences are costing the country dear. A generation ago, this mattered less but as Morocco begins to move up the value chain, open its economy more, strive to conquer new markets, it is turning into a major handicap. The likes of Attijariwafa Bank and Tanger-Med need highly trained specialists who speak fluent English. They often they have to resort to foreigners to fill the gap. Indeed many French graduates are keen to work in Morocco as opportunities are fewer in France.

Nonetheless the need for a Marshall Plan in education, at the very least a major push to train better qualified teachers and offer ordinary Moroccans a much better education than hitherto is becoming ever more pressing. Quality education in primary and secondary schools, let alone at universities is more often than not private, and costs a lot. Nothing feeds popular resentment so much as the sight of chauffeur driven plush cars collecting well-dressed youngsters outside the French schools.

Modernising the state

In the wake of the financial crisis of 1983, King Hassan gave the green light to modernise the state. Articulated by eminent public servants like Azzedine Guessous, Minister of Trade, Mohammed Berrada, Minister of Finance, and Abdellatif Jouahi who held a string of appointments in the state and private sector, Morocco was dragged into the late 20th century. By November 1994 when the whole world seemed to meet at the Casablanca conference which brought together Israeli and Arab companies face to face, Morocco basked in universal approval. Of course, the fact that neighbouring Algeria was slipping into civil war made the regional contrast even greater. Twenty years later however, the Moroccan state remains cumbersome as successive governments have failed to offer serious inducements to recruit well educated younger Moroccans.

Many civil servants are poorly educated and badly paid, a sure recipe for widespread corruption. Corruption however also results from what can only be described as a dual system of law making: the laws are voted by parliament but the décrets d’application are issued by the senior civil service and they interpret laws in a manner which is not always faithful to the spirit of the law. The statut avancé being negotiated by Morocco with the European Union should offer a solution but resistance comes from both the senior civil service in the kingdom and European private and state company interests who find they can manipulate Morocco’s system to their advantage.

Not all Moroccan institutions are typical of the isomorphic mimicry described earlier – notably the central bank, Bank al Maghrib, and the Haut-Commissariat au Plan whose reports put their finger on real issues. For all that, the debate on economic and strategic issues often remains hidebound: a more public debate on the real economic, social and foreign trade issues which confront Morocco remains a prerequisite to faster modernisation. The fact that most free trade agreements Morocco has signed with foreign countries have results which are detrimental to Moroccan industry, notably in the important textile industry is seldom discussed.

Certain reforms appear to achieve the exact opposite of what they set out to do. The directorate of foreign investment at the Ministry of Finance worked reasonably well. The government then decided to set it up as an autonomous body, Agence Marocaine de Développement Economique, at five times the running costs. Special representatives were appointed in major European capitals, at great expense, only to be recalled as their prerogatives were handed over to Moroccan embassies. Meanwhile the initial directorate was not “neutralised” – in other words abolished. Reforming the court system is another imperative if Morocco is serious about joining the 21st century. An arbitrary legal environment penalises. On the broader economic front, the government has enacted some necessary reforms like abolishing subsidies on oil and gas – helped by the sharp fall in the price of a barrel since last autumn. Oil and gas subsidies could, when prices were high, absorb the equivalent of 10% of GDP. But more needs to be done.

Nurturing new talent

For all Morocco’s success in attracting major foreign investors, it has been less good at helping smaller foreign investors let alone domestic small and medium size companies. Domestic investors are given official support if they are large enough to warrant access to the key decision makers in government. Otherwise they have to fight the bureaucratic maze of regulation and, often, corruption, especially at the local level. A new breed of provincial governor is emerging such as Mohammed Hassad, the current minister of the Interior who played a key role when he was posted as governor to Tangier in 2005-2012 and Marrakesh in 2001-2005. Such men are much better educated and interested in economic development than their predecessors. Too many officials at a local and regional level however are not well educated, notably on economic matters. They do little to listen to and support the country’s young entrepreneurs. The country thus misses out on any amount of young talent. Younger managers are moving into new sectors but woe betide he who has neither capital nor good connections. Some just give up and go abroad. Moroccan leaders need to break down class barriers.

All too often the government likes to rely of reports by outside consultants such as McKinsey but such people bear no responsibility towards the Moroccan people or parliament for what they do. Selling advice is a lucrative business but it is not always in the best interests of the client. Here again, Morocco needs to trust its own sons and daughters more than it has traditionally done. When outside advisers are called in by OCP group they meet their match, people who can understand what they are about and see through the fog of argument. No better symbol of how far Morocco has come could be found than the quarterly Economia review: its analysis of social, economic and management issues and trends matches the best in the West.

The economic management of Morocco still leaves much to be desired. If the country is to consolidate its aspiration to become a regional economic power its leaders have to confront certain issues head on. The administrative elite has far too much power for the good of the country. Too many of its members are still reluctant to have open debates and abide by clear and transparent rules. They have hijacked part of the agenda. Nothing frightens them more that bright young entrepreneurs. But, as Morocco trusts its young talent more, modern attitudes to governance to grow deeper roots and the kingdom’s economic progress should become steadier.