US NEWS & World Reports

By Mackenzie Ritter | Contributor

Young extras get a brush with fame, but at what cost.

Strolling this town on the western edge of the Sahara Desert, you might hear a man relating a conversation he had with Brad Pitt. Or a 20-something talking about how he saw Tom Hanks on the street. Or a girl gushing about how beautiful Emilia Clarke is in person.

Ouarzazate may be far from Hollywood, which hosts the Oscars this weekend, but it is a well-established location for international film shoots. It already was a tourist center when Atlas Studios, one of Morocco’s biggest movie makers, brought film work here decades ago. Since then, the city has hosted productions such as “Gladiator,” “The Red Tent,” “Babel” and “Game of Thrones.”

[RELATED: Is the Tanger-Med port good for Morocco?]

With competition fierce, Morocco is poised to go after an even bigger piece of the pie. Parliament has approved a rebate on expenses of major film projects, which is expected to go into effect this year. Proponents say the rebate will create jobs. But it does nothing to reform a system in which film workers sometimes sign contracts they can’t read, or earn below minimum wage. Teachers and parents fret that the allure of film work – and the money it brings in – keeps too many kids out of school.

Amine Tazi, general manager of Atlas Studios and CLA Studios, says foreign production companies come to Ouarzazate for desert scenery and cheap human capital. The new rebate will return 20 percent of their expenditures in Morocco if they spend at least $1 million and 18 days in country. The policy is expected to go into effect after a new national government is formed.

Excitement has grown since December, when Richard Lance Smotkin, Comcast senior vice president of global government affairs, led a delegation of U.S. filmmakers to visit Moroccan facilities.

Craftsmen, technicians and extras in Ouarzazate have a long history of working on Moroccan and international films – and besides tourism, there’s not much else. A vast solar power project in the desert nearby doesn’t employ many local people.

“You can tell just from the people in the street, the way they start getting ready for the projects,” Tazi says. One major production can employ hundreds of extras. When word of a production starts to filter out, residents shave their heads if they want to appear more Egyptian, dye their beards to look like they’re from Afghanistan, or do whatever else will help land a role.

It can be exciting, and lucrative. Boubker Ait El Caid, now 24, rates getting a role in “Babel,” a film that starred Brad Pitt and Cate Blanchett, as the best experience of his life. Abdelaziz Bouyadnaine, who bears a resemblance to Osama bin Laden, has appeared in nearly 100 films in the past 30 years.

Hanks was here for “A Hologram for the King,” and Clarke for season three of “Game of Thrones.”

But there is a downside, too, and residents point to local casting companies that have taken over the role of finding the technicians and extras for foreign productions.

Bouyadnaine, 59, says job seekers occasionally sign contracts in English or French that they can’t read; even if they can read it, they rarely know what they’re signing.

In order to get a job, prospective workers present a copy of their Moroccan identification card, Bouyadnaine says. Employers place a form in front of them, stressing that company rules are non-negotiable. If one won’t sign, there are dozens more who will.

Extras are paid by the day – typically 200-300 Moroccan dirhams ($20-$30). But they may spend long hours on the set, occasionally resulting in pay below the minimum hourly wage of 13.46 dirhams.

The burden often falls on Ouarzazate’s children. “The cinema has become a family business, where parents make a living from their children,” Bouyadnaine says.

Unlike one of Morocco’s major competitors, South Africa, no child labor laws apply to the film industry. The U.S. Department of Labor credits Morocco with making modest progress in clamping down on child labor, and movies appear to be far from the worst offender. More attention is focused on farming, domestic work, traditional crafts and the sex trade.

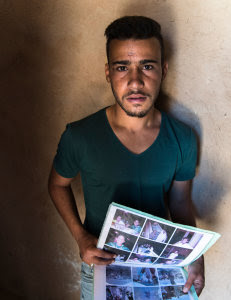

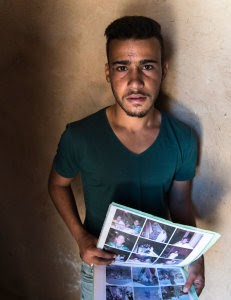

All the same, one 20-year-old man says he was on a set seven days after he was born. Leaning against the wall of his home in the kasbah, he scrolls through photos on his phone of himself in rags, plates of armor and other costumes.

[READ: Why Morocco’s burqa ban is more than a security measure.]

“I worked like a donkey,” says Salah, who didn’t want to use his last name out of fear it would hurt his career. But his parents took the money.

Ait El Caid said that in order to film “Babel,” he left his village as a 12-year-old with a virtual stranger, and he didn’t see his family for months. “There was no schooling happening,” he says. “My goal was only concentrating on the scenes.”

He since scaled back his movie work to finish his studies.

Nadia Zedek used to send her daughter Fatima unaccompanied to the studios more than four miles away from home. The girl is now 11 and gets an occasional speaking line. At times, Fatima has to miss school. Sometimes production crews come directly to her school to pull her out.

Zedek says she realizes the sacrifices involved in allowing her daughter to go in front of the camera. Teachers get angry that she is not in school.

“They tell me she shouldn’t be working – she is a bright student, she should be here,” Zedek says.

But the draw of film – and the power of local casting companies – is powerful.

Salah, the young man in the kasbah, says most of his friends and neighbors rely on work as extras. Challenging the casting companies to improve conditions is too dangerous.

“If we want to talk about our rights, we will never get another job,” he says. “If I talk, I won’t work again.”

Sapha Bouamara contributed reporting.