Bloomberg

More stories by Lin Noueihed

Morocco may need anything from five to 15 years to fully float the dirham, with further currency liberalization dependent on other reforms including strengthening the country’s export base and reducing the current-account deficit, central bank Governor Abdellatif Jouahri said.

Policymakers finally eased their grip on the dirham on Jan. 15, allowing the currency to trade 2.5 percent above or below the official peg, compared with 0.3 percent either side previously. The change implies a 2.5 percent depreciation in the dirham, “a start” that puts the onus on the government to make the next move, Jouahri said in an interview in Marrakesh on Monday, where he was attending a conference co-sponsored by Morocco and the International Monetary Fund.

“We have not reached that stage yet,” Jouahri said when asked about the prospects of a full float. If the government “adopts structural reform in the direction we’d like, we will be able to move faster towards the next stages of the foreign-exchange reform,” he said.

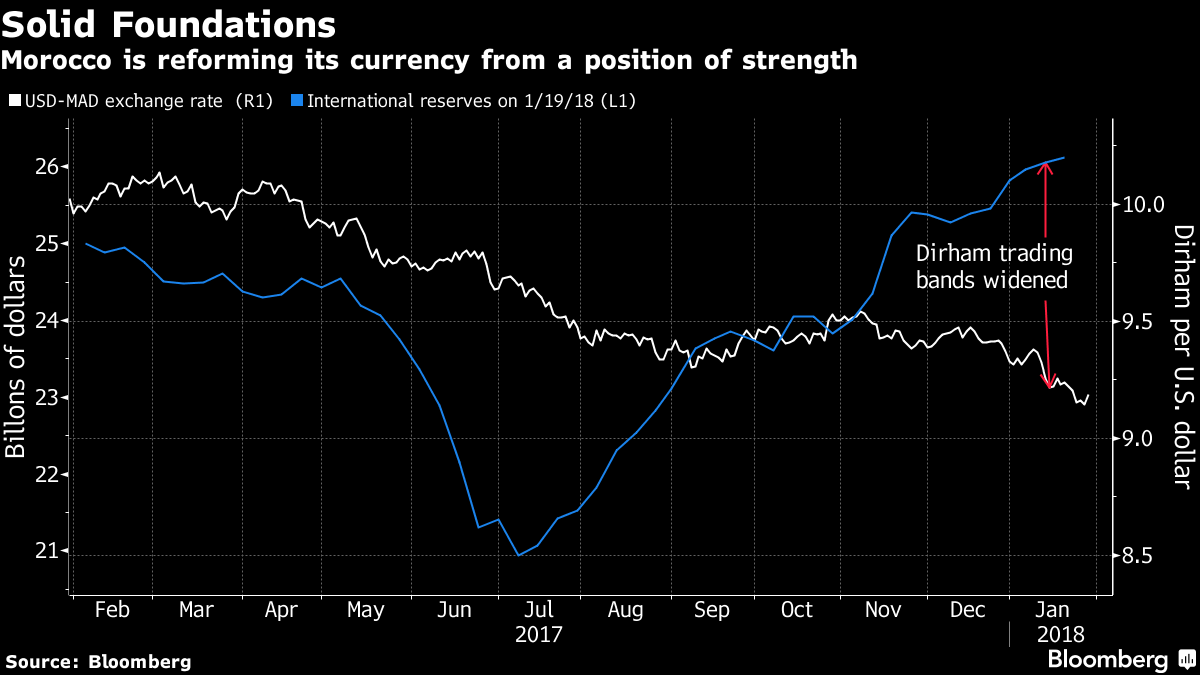

Currency liberalization is the centerpiece of Morocco’s efforts to transform itself into North Africa’s main business hub. The first stage, originally planned for mid-2017, was delayed after fears of a weaker dirham prompted a rush for foreign currency. But unlike in Egypt, which floated its currency to solve a crippling shortage of foreign exchange, the dirham has been stable since its band was widened, buoyed by ample reserves, low inflation and strong growth.

Morocco’s reserves, which dropped by about $4 billion in three months over the expected change last year, have now stabilized at more than $26 billion — or enough for more than six months of imports. Local lenders have bought only a fraction of the $20 million offered at a daily central bank auction, while the dirham has remained little changed against the dollar and euro.

The dirham will move more within its trading range in the coming weeks as banks adapt to the new system and as the economy strengthens, Jouahri said.

Morocco is an importer of grain and oil that has benefited from lower global prices in recent years, and relies on exports, remittances and tourism for its hard currency earnings — sectors that stand to benefit from a gradual dirham depreciation.

But the modest currency move was never likely to spur the kind of inflows that Egypt saw when its currency halved in value against the dollar in late 2016, analysts say.

“People expect this reform to yield more than what it can deliver,” he said. “This is not a magic wand.”

Since the trading band remains restricted, its effect on prices will also be limited, officials have said. Inflation is expected to average 1.9 percent in 2018, up from 0.7 percent last year, Jouahri said, giving the central bank room to reduce interest rates should the need arise. Morocco’s benchmark rate has been at a record low 2.25 percent since March 2016.

“We will do a flexible exchange rate, and then we will be moving to a phase when the central bank will limit its interventions on the market, and then let the domestic interbank market lead — and then when we proceed to flotation the market fixes the value of the dirham,” he said. “So what I am saying is, we will go gradually.”

— With assistance by Ahmed Feteha