Petroleum Economist

Chris Stephen

Project is the centrepiece of a strategy that promises to generate more than half of its electricity from renewables by 2030.

Morocco’s status as a global poster-boy for renewable energy was confirmed in May when it signed a $780mn contract to build Noor Midelt, a plant that solves solar energy’s biggest problem: what happens when the sun goes down?

The plant, to be built by a French-led consortium, combines two solar technologies to give it daytime and after-dark power generation. It will be the jewel in the crown of an impressive strategy.

Morocco’s 10-year renewables strategy runs like a blueprint for turning dreams into reality. It began in 2009 when the government confronted a looming energy crunch. Mass electrification during the 1990s brought electricity into almost every home, but also led to power demand increasing by an average of 4-6pc per year. A growing population, now 34mn, and Morocco’s reliance on imported fossil fuels for 90pc of its power generation, meant it faced an increasing financial headache to keep the lights on.

Lacking the oil and gas assets of some of its neighbours, Morocco turned to a trio of natural resources. Along with abundant sunlight, the country has fast-flowing rivers running off the Atlas Mountains that are suitable for hydroelectric power. And, occupying Africa’s junction with the Atlantic and Mediterranean, there is plenty of wind.

A National Energy Strategy was published and a pair of agencies were set up to coordinate renewable development: the Moroccan Solar Agency, later renamed the Moroccan Agency for Sustainable Energy (Masen); and the National Agency for Development for Renewable Energy (Aderee). The energy market was then put on a commercial footing, with fossil fuel subsidies phased out.

Ten years on, investments in hydro, solar and wind account for 35pc of power generation. Coal and gas-fired power stations account for 64pc and the expansion of the Jerada coal-fired power plant means output is increasing. In total, Morocco produces 9.085GW of electricity.

The government has pledged that renewables will produce 52pc of electricity by 2030. A $1bn investment has been made to construct 16 wind projects. Morocco already has eight hydro-electric projects, the earliest dating from 1953, including dams originally built for water reservoirs that have been converted for hydroelectric generation. But it is solar that has caught the headlines.

Sundown solar

A dramatic white tower, rising 243m from the central desert, is the centrepiece of Morocco’s largest solar plant, Ouarzazate. Its panels and mirrors cover 3,000 hectares (11.6 miles2), an area equivalent to two-thirds of Manhattan. It is solar power, but with a difference.

Some 90pc of the world’s solar energy plants operate with solar panels converting sunlight to electricity—photovoltaic power (PV). The problem with PV is that power ends at sunset, leaving nothing for evening demand. Many states solve the problem with the use of batteries or meeting demand surges with traditional thermal power stations.

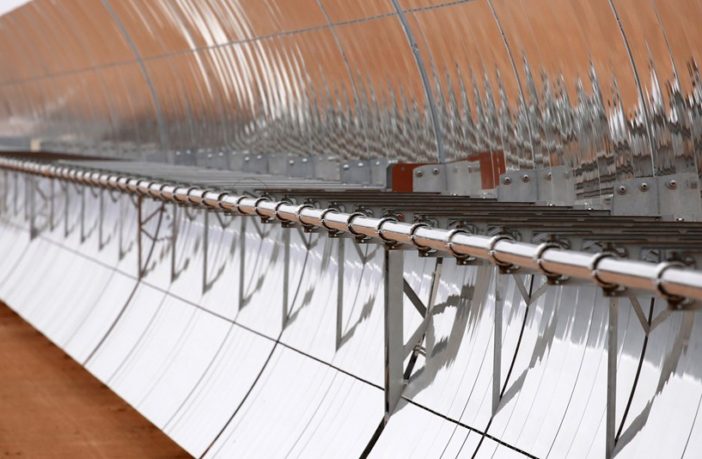

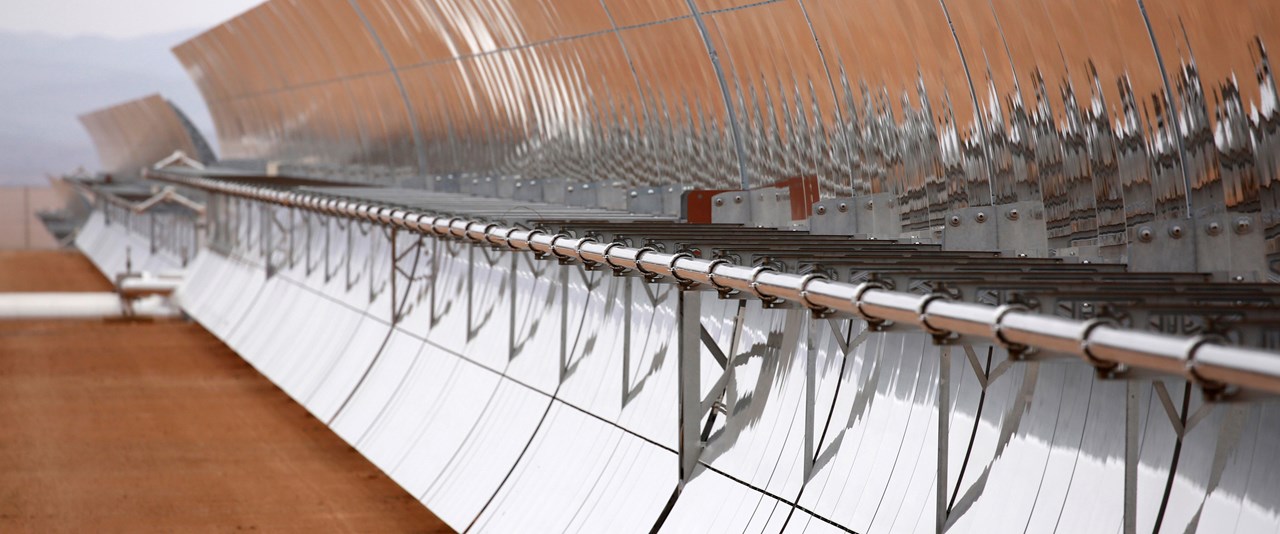

Ouarzazate, built in 2016, is different. By day, banks of hundreds of mirrors reflect sunlight onto the tower which holds a column of liquid salt. The salt is heated to 400° C, turning water into steam to turn turbines. The operation, called concentrated solar power (CSP), provides electricity for five hours after sunset.

Noor Midelt, due to begin generation in 2022, will integrate PV and CSP. During daytime, two PV plants will generate 420MW. After the sun goes down, two CSP plants take up the slack, producing 380MW. Backers of the project, to be built by a consortium of France’s EDF, UAE’s Masdar and Morocco’s Green of Africa, boast that it represents a coming-of-age for solar power. “There will be a world before, and a world after Midelt,” says Masen chief executive Mustapha Bakkoury.

The technology is pioneering and the International Energy Agency’s executive director Fatih Birol has lauded Morocco’s “impressive track record for developing solar technologies”.

Political bedrock

Less eye-catching, but equally important, has been the political stability that made its long-term energy strategy, and the loans required for it, possible. Solar power installations require substantial capital investment. Ouarzazate cost $600mn, with two-thirds of it coming from the World Bank. Noor Midelt’s array of backers hints at the complex financing needed to make projects a reality: African Development Bank, Clean Technology Fund, European Commission, European Investment Bank, French Development Agency and World Bank.

Solar power advocates are fond of pointing out that, once installed, the system effectively lasts forever; running costs are limited to pumping water to regularly clean mirrors and panels. The reality can be more complicated if loans are repaid from electricity sales receipts, and interest charges mean repayments cannot be stretched out indefinitely.

Morocco, Africa’s fifth-largest economy, has avoided the recent turbulence of its North African neighbours Algeria, Egypt, Libya and Tunisia. In 2011, King Mohammed VI answered pro-democracy protests with a new constitution transferring some of his powers to parliament, ensuring relative stability. In April, the World Bank commended Morocco’s “sound fiscal and monetary policies”.

The political picture is not entirely rosy. There are periodic protests against corruption and complaints that investment is concentrated in the coastal cities. This was highlighted with the $2.1bn high-speed railway, the first in Africa, linking Casablanca and Tangier; it triggered protests from the south, which has no rail service at all.

Morocco imports natural gas from Algeria (via a pipeline that connects Algeria to Spain and Portugal), but relations with its eastern neighbour are at times frosty. The government plans to spend $4.6bn building a coastal LNG import plant at Jorf Lasfar, allowing it to shop around for its gas. Morocco may yet find substantial gas reserves of its own, with Italy’s Eni exploring offshore and the UK’s Sound Energy exploring the onshore Tendrara field near the Algerian border.

MENA solar template

Morocco’s renewables success story is a template for other MENA states, not least because those rich in fossil fuels have spare cash to invest in solar plants. The UAE is noted for doing just that. But in a region that provides half the world’s oil and more than a third of its natural gas, abundant cheap energy means the required incentive can be lacking.

Bassam Fattouh, director of the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, argued last October that MENA states should stop selling fossil fuels at discounts to domestic power plants as the practice makes investment in solar uneconomic. Introducing market rates for domestic fossil fuel sales would spur the development of solar power, in turn freeing up more oil and gas for export.

For the moment, the world’s oil supply glut makes such a strategy problematic for most MENA states. Opec wants to trim supply to defend the oil price, rather than let more appear on the world market. But for those states wanting to invest in solar, Morocco has provided a valuable financial and technological blueprint for how it can be done.