Jessica Morris

Round Earth Media

Fadel Senna, AFP/Getty Images

Chafik Chraibi, right, head of the Moroccan Association for the Fight against more

It’s been eight years since Hinde Bariaz went to a medical clinic in this capital city to obtain an illegal abortion. All these years later, she remembers the experience vividly.

The clinic was dirty, Bariaz said, with air heavy from cigarette smoke. “The doctor was smoking. I had to wonder, ‘Am I in a market?’ It was not safe at all,” Bariaz, 35, said. “You just go inside, you finish the operation and you leave as quickly as possible.”

An estimated 800 women get abortions every day in this North African kingdom, and many face the same conditions as Bariaz because abortions are illegal unless the life or health of the mother is at risk. But that may soon change.

In March, King Mohammed VI ordered that laws restricting abortion be eased in cases of rape and incest. In Morocco, when the king wants something it usually happens: The parliament is likely to approve the change within weeks.

The king’s decree came after a controversy involving a Moroccan physician who spoke out on the issue. The Moroccan Ministry of Health fired Chafik Chraibi, chief of obstetrics at a hospital in Rabat, after he criticized the country’s abortion laws in a French TV report in December, but he got his job back in March following an outcry on social media.

“Women who do not get abortions end up having babies” and many “abandon their babies and disappear,” Chraibi said.

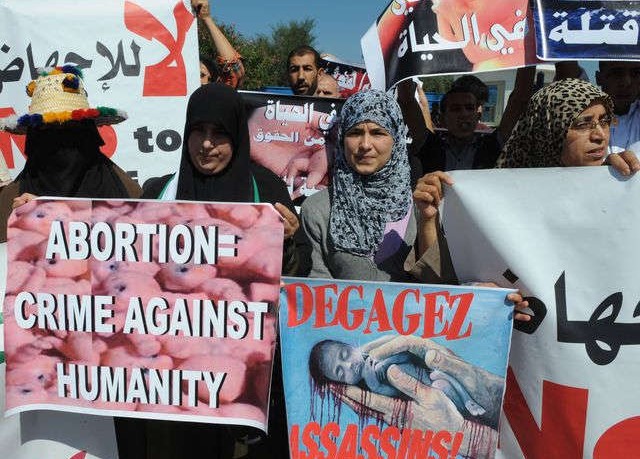

The push to legalize some abortions is encountering opposition from the Justice and Development Party, the conservative Islamist group that leads the government. But Mehdi Bensaid, a young member of parliament who supports liberalizing the country’s abortion laws, said “this is a good time” to pass the law because many non-profit groups and other political parties are backing the change.

Morocco’s current anti-abortion law is common in the Muslim world. A 2014 U.S. government study found that in 47 nations with a majority of Muslims, 18 do not allow abortions under any circumstances besides saving the life of the pregnant woman, while 10 allow abortion with few if any restrictions.

In Tunisia, another majority-Muslim country also in North Africa, abortion has been legal within the first three months of pregnancy since 1973.

Doctors, activists, and professors say some Moroccan women try to induce an abortion by ingesting harmful herbal infusions or pills, laying on the sweltering floor of a hammam (bathhouse) or even inserting a sharp device into their vaginas.

But women with money can usually find doctors willing to provide a safe abortion, according to Imane Khachani, a gynecologist in Rabat. These abortions typically cost over $1,000, a huge amount in a country where the minimum wage is just $300 a month.

“Abortion is a very complex issue,” Khachani told Al Jazeera. “But let’s keep in mind: no matter what our opinion about the act per se is, what counts at the end of the day is what this woman, patient, or girl sitting in front of you wants to do with her body.”

Bariaz’s experience with clandestine abortion has led her to become a staunch advocate for legalized abortion. An English teacher during the day, she runs a hotline in her spare time that assists women who want to carry out abortions using pills.

One pill she recommends is a medicine used to cure symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. One of its many dangerous side effects is termination of pregnancy. It can be easily found at local pharmacies in Morocco and costs only about $12.

“There are many girls who call — not only girls, but sometimes boys call,” Bariaz said. “After living this experience I know the suffering of girls who cannot afford the money, who are unmarried and get pregnant, whose parents know nothing about their story.”

Moroccans are opposed to abortion not so much because of their Muslim religion but because of the societal taboo against sex outside marriage, said Abdessamad Dialmy, a professor who studies Islam and sexuality at the University Mohammed V in Rabat.

“When you ask girls, when you ask mothers, when they face an illegal pregnancy, the challenge is not to deal with God. The problem is with the community,” he said.

Some Moroccans want to go even farther than Tunisia — seeing all abortions legalized.

“You do not build a democracy without giving women the right over their bodies,” said Ibtissam Lachgar, co-founder of Morocco’s Alternative Movement for Individual Liberties. “A lot of people support us on Facebook, but there aren’t many who are brave when we organize gatherings.”

Bensaid, the parliamentarian, thinks it will take five or 10 years for Moroccan women to have the right to abortions the way Tunisians do. “Maybe one day we will have the same law,” he said. “We must fight to win.”

Morris produced this story in association with Round Earth Media, a nonprofit organization that mentors young international journalists. Youssra Rahal and Hayden Crowell contributed to the reporting. Morris and Crowell spent several months in Morocco on a School for International Training Study Abroad journalism program.