Face2Face Africa

Mildred Europa Taylor

Staff Writer

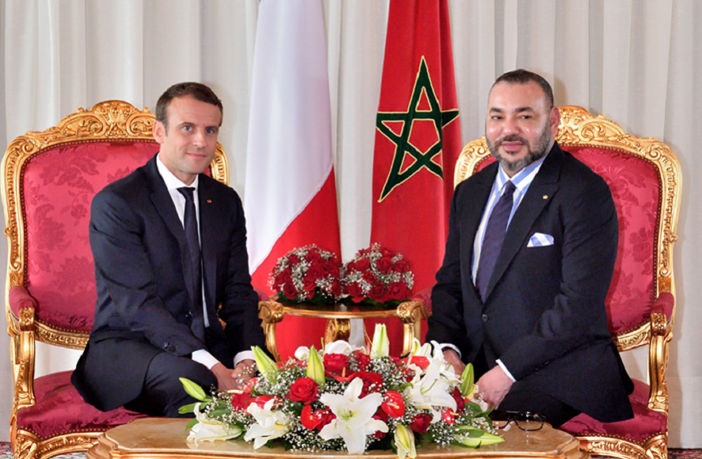

Morocco’s King Mohammed VI (right) and French President Emmanuel Macron. Pic credit: Morocco World News

Following the over $1 billion that has been accumulated from donations across the world to restore the fire-ravaged Notre-Dame cathedral, debates are ongoing over whether the large sum could have been spent on other causes, including helping the poor and vulnerable in conflict-ridden societies.

In Africa, many leaders have been sending their condolences since the disaster occurred, with even a chief pledging to donate to help rebuild the Paris landmark.

Scores of Africans have subsequently expressed disappointment at their leaders for being quick in sympathizing with the West when disaster strikes, but decide to remain mute about calamities in their own backyards.

These discussions have not deterred Morocco from being the first African country to announce that it will contribute to rebuilding the Notre-Dame cathedral.

“The Moroccan embassy in France has commissioned its ambassador, Chakib Benmoussa, to inform the Archbishop of Paris, Michel Aupetit, that Morocco’s King Mohammed VI will make a financial contribution to the reconstruction of Notre Dame Cathedral,” The Maghreb Timesreported this weekend.

The Moroccan king has also expressed his condolences to the French authorities for the burning of the cathedral, which he described as a symbol of Paris, the history of France and an important site for millions of Christian worshippers, the report added.

In just 24 hours, a fund to restore the medieval Notre-Dame cathedral that was devastated by fire hit over $1 billion last Thursday, with donations still pouring in from around the world.

The Paris landmark was heavily damaged last Monday night after a fire broke out during a Roman Catholic Mass and quickly spread to the roof and iconic church spire.

Firefighters managed to save the 850-year-old Gothic building’s main stone structure, including its two towers, but the spire and roof collapsed. There are also fears that an unknown number of artifacts and paintings have been lost.

News of the blaze sent shockwaves across the country. Donations and messages of support have since been flooding into France from across the world. Personalities, billionaires, companies, and institutions from around the globe have stepped in to help France rebuild its symbol of history and culture.

In Africa, a chief from a traditional area in Ivory Coast pledged financial support towards rebuilding the iconic structure in Paris.

“I am in full consultation with my elders – we are going to make a donation for the rebuilding of this monument,” Amon N’Douffou V of Sanwi in southeastern Ivory Coast said on Tuesday.

“I couldn’t get to sleep because I was so disturbed by the pictures,” the chief said of the structure which he claimed played a huge part in his kingdom’s history in the 17th century.

Ivory Coast was a French protectorate in 1843, then a colony from 1893 to 1960. But King Amon’s strong bond claim has to do with events that occurred at the end of the 17th century, at the time of the Sun King, Louis XIV.

Aniaba, a prince of the kingdom was, in 1687, taken to France and then baptized in the cathedral. At the time, French traders had fully established themselves in the kingdom.

Aniaba, who was then 15, and a son of the chief of the Eotilé ethnic group and Princess Ba, was taken to Paris by the Chevalier d’Amon as a pledge of loyalty to Louis XIV. In Paris, he experienced a “mystical revelation” at the sight of the Notre Dame cathedral.

Louis XIV became Aniaba’s godfather and protector. He was, after three years in France, baptized, adding the name of Louis to his own. Now Louis Aniaba, he joined the king’s cavalry regiment, becoming the first black officer of the French army. He learned to read and write, as well as, fencing and horse riding.

In 1701, Aniaba returned to Ivory Coast following the death of his father to “take his succession,” but what happened to him next is not known.

While in Paris, it is said that Aniaba received a huge pension and lived “like a gentleman of the time: with servants, horses, debts, women and children.”

These reasons should not be the basis for a donation, critics say, wondering why the traditional ruler would rather not divert those funds towards development aid for African countries or even the Cyclone Idai victims.

For those Africans worried about the unknown number of paintings and artifacts that remain missing, they should rather channel their energies towards getting back the artefacts that were stolen or sold illegally to museums and private art collections overseas, observers say.