The Washington Post

By Jackie Spinner

Malak Nahass, 32, sits in a cafe in Rabat, Morocco’s capital. She says she was taunted and injured in a street attack in Rabat this year and that the police appeared unconcerned about her complaint. A bill being debated in Parliament would criminalize public harassment of women.

Malak Nahass was walking on a busy street near a Rabat beach one afternoon about six months ago when a stranger approached and started taunting her. The situation quickly escalated.

She is always on guard in public because she is used to being harassed, Nahass said. “I try to be invisible.” But this time, she couldn’t make herself disappear. The young man grabbed at her, and when she ran, he threw rocks at her, hitting her in the head. The deep cut she suffered required five stitches.

Nahass, a 32-year-old sound engineer, went to a police station to report the attack. The officers took the information and assigned her a case number. “They almost didn’t want to write down the description,” she recalled. She went back the next day to see if they had caught the man she described. The officers said they had looked around the neighborhood but had not found the suspect. When she followed up again a few weeks later, they accused her of harassing them.

“Can you believe it?” she said, shaking her head.

Last month , the Moroccan Parliament once again debated legislation long sought by women’s rights activists here that would make it a crime to harass a woman in public, whether physically or verbally. Under the latest proposal, a conviction could draw a month to two years in prison. But the bill remains mired in political wrangling between reformers and members of the conservative parties.

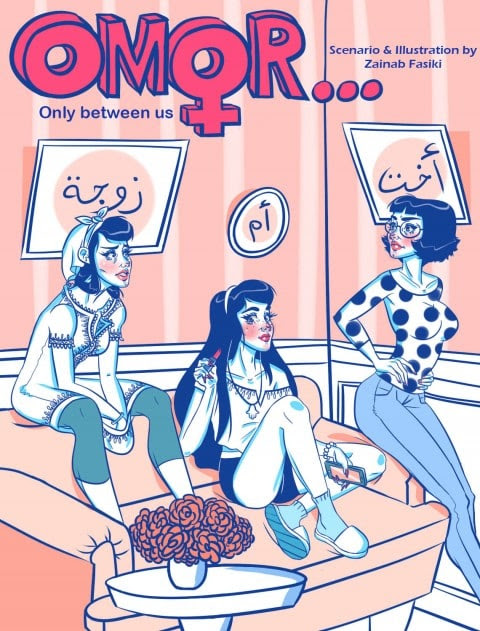

Comic artist Zainab Fasiki uses her art to show strong and unafraid women. “There is a lot of work to do” if traditional views of women in Arab countries are to change, she said. (Zainab Fasiki)

[How cronyism and lack of accountability are holding Morocco back]

On paper, the anti-harassment law would be a big step, particularly for a country that wants to be seen as a moderate Islamic hub compared with its neighbors in the rest of North Africa and the Middle East. This year, Morocco banned the manufacture and sale of the burqa, and its king, Mohammed VI, often pops up on Instagram in jeans and hip shades. The reality, however, is far more complex. Morocco is a deeply conservative, patriarchal society with a ruling Islamic party that won handily in a parliamentary election last year.

“Everything that concerns women’s rights is connected to religion,” said Khadija Ryadi, former president of the Moroccan Association of Human Rights.

In September, Morocco rejected 44 of 244 recommendations made by the U.N. Human Rights Council following its latest review of the country’s rights record. All 44 pertained to either women’s rights or individual rights, including laws that prevent women and men from inheriting equally and that deny rights to children born out of wedlock.

In rejecting the recommendations, Morocco said its constitution must adhere to Islamic law — a striking illustration of the traditional and religious thinking hampering the country’s efforts to appear as a beacon of moderation in the region. Nowhere is the contrast between image and practice more evident than in Morocco’s approach to gender rights. Although its constitution guarantees equal rights for women, it does so with caveats, noting that these rights must respect “the laws and permanent characteristics of the kingdom.”

It’s a constant balancing act, said Noufal Abboud, the Morocco country director for international human rights organization Search for Common Ground. “You can bring the most progressive law to Morocco, but the society will not accept it,” he said. “It’s a man’s society.”

Human Rights Minister Mustapha Ramid, embroiled in controversy after he called gay people the Arabic word for “dirty” or “scum,” declined an interview request.

There have been some changes since Mohammed VI became king in 1999, pledging greater rights for women.

[Why Jordan and Morocco are doubling down on royal rule]

In 2004, Morocco revised its family code, called the “moudawana,” giving women broader rights in custody, marriage and divorce. The changes came after bombings in Casablanca killed 45 people, still the country’s deadliest terrorist attack. Although the Islamic parties were not implicated in the bombings, the government was able to use the atmosphere of anti-extremism they generated to win concessions from them on some of the king’s changes, most prominently the moudawana.

But the monarch can go only so far, said David Alvarado, a journalist and media consultant.

“The king has two faces,” he said. “The Western face is progressive, but internally he is traditional. He can’t be progressive here in Morocco.”

Human rights activists would like to broaden the family code even more — to grant women equal inheritance rights, for example. The code uses an interpretation of Islamic law to mandate that women can inherit no more than half of what men do. The president of neighboring Tunisia has called for his country to amend its inheritance law, and in July, the country passed a law aimed at preventing “all violence against women.” Both moves sparked outrage from Tunisia’s clerics and conservative politicians. Algeria also has a domestic-violence law, passed in 2015, that protects women from abuse.

In Morocco, although Islam is used as the rationale, it’s actually culture holding back changes affecting women, said Amal Idrissi, a law professor at Moulay Ismail University in the city of Meknes. “It’s not religion,” Idrissi said. “It’s patriarchy.”

Harassment is perhaps the clearest flash point. A 2009 national survey estimated two-thirds of Moroccan women have experienced violence at one point in their lives, and younger women in particular are fighting back.

In June, a 24-year-old woman was viciously attacked on a public bus in Casablanca. The assault, which was filmed and posted online, doesn’t show passersby or the driver trying to intervene, even as the woman’s clothes are ripped off and she cries out for help.

Hundreds took part in a protest in Casablanca in August after the video went viral to demand the creation of laws protecting women from such assaults.

Zainab Fasiki, a 23-year-old comic artist from Fez, drew a cartoon after the bus attack that went viral on social media. It shows a woman, her clothes pulled off, looking out sadly from a bus. The caption reads in English: “Buses are made to transport people not to rape girls.”

Fasiki said she tried to organize a protest in Fez like the one in Casablanca but too many women were afraid to participate. “So it didn’t happen,” she said.

She uses her art to show women naked and strong and unafraid, she said. (When a woman is attacked in Morocco, even sympathetic women often will ask what she was wearing.)

“Women in Arab countries are still seen as virgin girls sitting in their homes or wives who respect their husbands,” she said. “There is a lot of work to do to change those ideas.”

Nahass, the sound engineer, said she has learned to go into “warrior mode” when she’s out in public, even in Rabat, the capital, considered one of the country’s safest cities. She tries to ignore the taunts she hears daily. But often, men just come up and grab her, reacting to her indifference by saying she’s ugly anyway. “In a way, you get used to it,” she said.

Today’s WorldView

Sign Up

After the attack near the beach, she wanted to leave. “I just got so depressed,” she said. “I hated this country.”

Kenza Allouchi, 21, a recent film school graduate in Rabat, said even if the expanded anti-harassment law is eventually passed, she isn’t sure it will do much good.

“Whether we go out dressed well or not — they would accost us even in pajamas with words of harassment,” she said. “A law is good, but an education would be much better.”

This story was supported by a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.