Financial Times

AFP

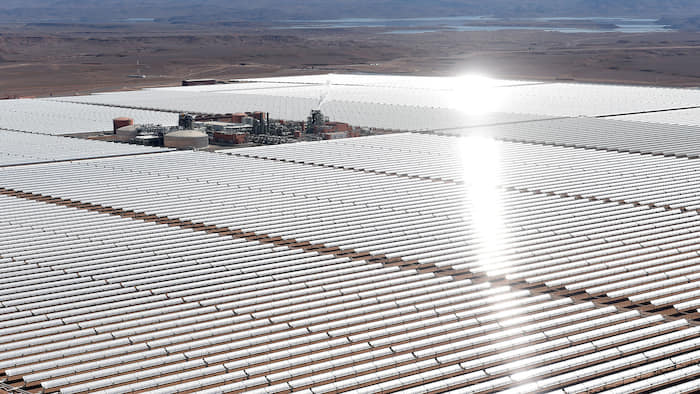

Rays of hope: the Noor 1 solar power plant in central Morocco © AFP

Until this year, the Moroccan town of Ouarzazate was best known for its ancient-looking kasbah façades, used as an exotic backdrop in many Hollywood movies. But now, it has a very 21st century landmark: the world’s largest concentrated solar power (CSP) plant.

Sample the FT’s top stories for a week

You select the topic, we deliver the news.

With 500,000 parabolic mirrors, the plant — Noor 1 — has a generating capacity of 160 megawatts — equivalent to that of a conventional single gas turbine power station. It is the first of three CSP plants at the site that will eventually be capable of generating more than 500MW at peak output.

Noor is the most high-profile component of Morocco’s ambitious push for renewable energy, which will be showcased when the country hosts COP 22 in Marrakesh. The government has committed to an unconditional 17 per cent reduction in greenhouse emissions by 2030 compared with business as usual, and has adopted a multi-pronged plan combining renewable energy development and improved energy efficiency.

Energy independence has been the main impetus for the programme. Morocco lacks significant fossil fuel supplies of its own. However, electricity demand is growing at 5-6 per cent a year as the country pushes its long-term programme to wean its economy off a dependence on agriculture towards industry.

In 2009, the state set an ambitious target to produce 42 per cent of its electricity from renewable sources by 2020 — a goal that officials say they are on track to meet. This was then extended last year at the COP21 summit in Paris, when King Mohammed VI announced a new goal of 52 per cent by 2030.

The country has received plaudits for both the scale and success of its programme. Michael Taylor, a senior energy analyst at the International Renewable Energy Agency, says Morocco has been helped by factors including strong institutions, funding from bilateral and multilateral agencies and ample supplies of wind and sun. “It’s kind of a confluence of influences that have allowed them to step up early and, of course, they’re reaping the benefits of those renewables now, earlier than others,” he says.

Moroccan officials say they can offer lessons for other countries looking to increase their use of renewables.

“It’s not just about money. It’s much more a matter of capacity building, technology transfer and the right policies,” says Said Mouline, director-general of the Moroccan Agency for Energy Efficiency (AMEE). “We have a sustainable environment approach for all sectors. It’s in our constitution and there is will at the highest level of the state.”

Over the past seven years this has translated into 54 action plans covering all economic sectors. They go beyond installing renewables to cover agriculture, land use, forestry, waste, and industrial policies. As well as establishing a nascent renewables industry, subsidies on fossil fuels have been phased out and energy efficiency encouraged. “We have a low price in renewables, we have industrial integration, and we have job creation,” says Mr Mouline.

The Noor project has caught the attention of energy analysts around the world. The plant uses mirrors that reflect sunlight to heat liquid, which can power a turbine. Unlike onshore wind and solar photovoltaic schemes, CSP plants can store energy in superheated liquid that can be used later to drive turbines. This makes it one of “the key technologies for unlocking those very high levels of renewable power generation,” says Mr Taylor.

But it is the project’s funding model has been singled out as one of Morocco’s key achievements. “They’ve been a game changer,” says Anne Lapierre, partner for energy and projects with law firm Norton Rose Fulbright. She was involved in advising Masen, the government agency behind the venture, on the tendering process, which gave it tight control over all aspects of the programme and allowed it to keep costs down.

Masen was able to use funds borrowed by the government from multilateral agencies and banks and then lend the money on to the project company. “It was the first IPP [independent power producer] where the bidders were meant to bid fully-financed. So the winning bidder was accessing the financing, which is a total disruption,” Ms Lapierre says.

Through Masen, the government also became a minority shareholder in all the project structures. “We had to simplify things as much as possible. The most complicated things can be realised if they are simplified,” Mustapha Bakkoury, head of Masen, told the FT ahead of Noor 1’s launch earlier this year.

After a restructuring last year, Masen is now responsible for the development of all Morocco’s renewables. It also has the capacity to invest abroad.

Other countries, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, have shown an interest in the country’s approach and Ms Lapierre believes the Noor funding and development model could work as a template for future renewable projects.