Women News Network

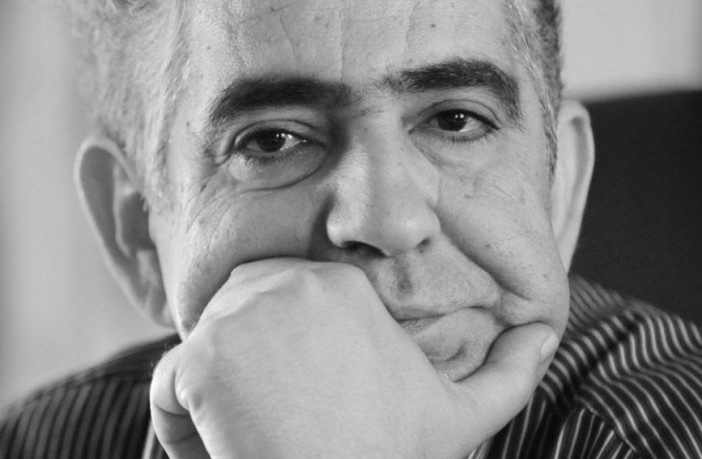

Jessica Buchleitner with Driss El Yazami

WNN Interviews global

Mr. Driss El Yazami, Chair of Morocco’s National Council on Human Rights/Président du Conseil national des droits de l’Homme (CNDH)

(WNN) Rabat, Morocco, NORTH AFRICA – In the same week Egypt celebrated its five year anniversary of the legendary uprising that served to oust former President Hosni Mubarak and ignite a series of protests across Arab nations, on January 27, 250 of the world’s eminent Islamic leaders convened to discuss the rights of religious minorities and the obligation to protect them in Muslim majority states at the invitation of King Mohammed VI. The result was the Marrakesh Declaration.

This latest installment of Morocco’s push for human rights protections and policy reform is in addition to other measures where Morocco has been making headlines for its reformations and actions on various human rights policies and initiatives for the past two decades.

As a nation, Morocco is a signatory to the United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, Convention against Torture, the UNICEF Convention on the Rights of the Child, and the Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW). Since 2008, more than 80 reports have been issued on human rights in Morocco from Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, Freedom House, and the State Department.

In December 2008, King Mohammed VI publically banned discrimination against women and officially lifted all Morocco’s previous reservations on CEDAW, stating “Our country has become an international actor of which the progress and daring initiatives in this matter are readily recognized.”

Following the Middle East revival and reshaping ripple effect the Arab Spring brought to the region, Morocco reformed its national human rights oversight body in March 2011 after King Mohammed VI announced the establishment of a National Human Rights Council (CNDH) to replace the former Advisory Council on Human Rights (CCDH). This was considered a significant move since the royal decree creating the CNDH, and Article 161 of the 2011 Constitution enshrining it, established autonomy for the council, allotting it the power to investigate allegations of human rights violations, summon individuals to give evidence in its investigations, and to act as an early warning mechanism to prevent such violations. It also has the power to visit detention centers and inspect prison conditions, establish regional authorities for protecting human rights, and examine and make recommendations on how to bring legislation in line with the Constitution, international human rights treaties, and international law. The CNDH is also tasked with enriching the debate on human rights throughout the Kingdom and providing an annual report, as well as special thematic reports, to the King via 13 regional commissions mandated to receive complaints about any allegations of human rights violations.

In the past year, Morocco has introduced human rights policies in the areas of migration, women’s rights, and the court system, including adopting a new policy providing protections for migrants and asylum seekers (November 2013), an amendment to the law so that rapists can no longer be exonerated by marrying their victims (January 2014) and an approval by the Council of Ministers, chaired by King Mohammed VI, of the draft law on military justice, which will exclude civilians from being tried in military courts (March 2014).

Driss El Yazami, President of Morocco’s National Council on Human Rights (CNDH) and Interim Executive Editor Jessica Buchleitner discuss CNDH’s plans for continued reform, Morocco’s affiliation to the CEDAW ordinance, its recent reforms on migration policy and engagement with civil society in addition to related policies and changing laws referenced in the comprehensive report CNDH released on October 20, 2015, Gender Equality and Parity in Morocco: Preserving and Implementing the Aims and Objectives of the Constitution (pdf).

Jessica Buchleitner (JB): The National Council on Human Rights (CNDH) has been taking considerable actions in regard to gender equality in Morocco. In October 2015, you held a press conference regarding a newly released report Gender Equality and Parity in Morocco: Preserving and Implementing the Aims and Objectives of the Constitution four years after the new constitution, ten years after reforming the Family Code, and 20 years after the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action came about. What were the most important findings in this report on the basis of gender equality? Where are there still gaps and areas to improve and what are your policies for making these improvements?

Driss El Yazami (DEY): The report is based on the latest academic research regarding the situation of gender equality in Morocco. There are some silent evolutions in our country that the report findings were able to confirm. The first is the rate of education and the second is the rate of children per Moroccan woman. The rate of children per woman has decreased to 2.10 children born per woman. In the labor markets more Moroccan women are working and there are many improvements since the 2004 reform to the Family Code in this regard. However, we gleaned from the report that there is still some degree of discrimination in the law and we are continuing to ask for reforms regarding the family code.

In regard to the labor market, until five or six years ago the rate of activity for Moroccan women was lower- about 29 percent participation. In the last five years we now have about 33 percent. While this is a slight increase, for us it shows there is little to no more progress in this area, which, from our point of view, shows discrimination. We are also concerned that the Moroccan government did not issue the draft for high authority and quality against discrimination. Now the draft work is at the parliament and we are concerned about it since the current draft is quite weak. According to Article 19 of the constitution we need a more powerful solution.

We are also still concerned about the marriage of girls in Morocco. We have about 30,000 young Moroccan girls who are still married under the age of 18 even through the new 2004 Family Code raised the legal age of marriage from 15 to 18 years old.

JB: Morocco’s introduction of the groundbreaking new Family Code in 2004 gave women greater equality and protection of their human rights within marriage and divorce, in accordance with Article 16 of the CEDAW treaty. What protections were introduced in this reform?

DEY: The original Moudawanah, or Family Code, was introduced following independence in 1957. It put wives in a subordinate position. Morocco ratified CEDAW in 1993 and in cooperation with King Mohamed VI and the Prime Minister of Morocco we introduced the new Moudawanah in 2004. The Code changed marriage and divorce laws in addition to raising the legal age for marriage from 15 to 18 years of age while also granting women joint responsibility of the family with their husbands, as well as equal rights in marriage and access to property upon divorce. The code also promotes women’s participation in politics and society and introduced family courts to ensure that the new rights are enforced.

(This introduction occurred alongside other reforms concerning the human rights of women, including changes to the Labor Code to introduce the concept of sexual harassment in the workplace (2004), changes to the Penal Code to criminalize spousal violence, changes to the Nationality Code (2007) to give women and men equal rights to transmit nationality to their children, and changes to the Electoral Code, to increase women’s political participation by creating a “national list” that reserves 30 parliamentary seats for women (2002).)

Our Family Code, especially in 2016, was designed to give men and women the same human rights in order to conclude marriages, divorce and regarding children, especially when men and women are from another nationality. In our country there are marriages with those from abroad such as French, Belgians, and Dutch so we also have to give the husbands with other nationalities the same rights as the Moroccan husbands.

JB: CNDH’s recent proposed reforms to women’s rights to the inheritance law section of the Family Code were very controversial. What will it take to make such recommendations a reality and why the controversy?

DEY: In supporting its recommendation, the CNDH referred to both national and international law, citing Article 19 of the 2011 constitution and Article 9 of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), of which Morocco is a signatory party.

It is controversial because the Prime Minister said in public interviews that we were attacking the religion of Islam and that the holy Quran is against this. He then asked me to apologize to the Moroccan society. From my point of view, a politician or political parties have the right to be against certain recommendations. The fact is that it is the first time in the Islamic world that a public institution, especially a commission of human rights, is asking for these things. Until now this was a feminist issue and one among Muslim intellectuals. It will take more time and has taken time to implement this recommendation. We need more discussion, and mainly for the religious leaders to launch more important discussions about the issue. There are already some intellectuals and some religious leaders in Morocco and in other countries asking for equality in inheritance. It will take time. Some people will even use the religion against us on this issue. The fact is the public debate is now launched in our country and there is so much positive public reaction within the Moroccan society and in other neighboring countries like Tunisia, Algeria and Lebanon, but this issue will take some time.

The fact that the debate is launched in our country is a good thing. When you look at neighboring nations in our region, people are killing each other over the freedom to debate. In some nations democracy is weak. We have to maintain our capacity to discuss sensitive issues in a decent and democratic way.

JB: CNDH has also been at the heart of Morocco’s push for democracy. How does this position help the citizens of Morocco in regard to their human rights?

DEY: The reformation of human rights and democracy that is happening in Morocco now is a process that took the West some centuries to achieve. Beginning with the Italian Renaissance, etc… it takes decades to achieve a better political process. This year is a landmark year for us because we have at least 15 draft laws in discussion at the Moroccan Parliament related to human rights. We have four draft laws on justice and we also have a law for civil society regarding the rights to present petitions and the democratic rights of civil society to also present draft laws to the parliament. We have laws regarding discrimination and even the right of access to information. I think in 2016 we will have a much stronger framework in Morocco in terms of democracy and human rights.

What we also need to do is to train activists. While a strong legal framework is pertinent, it is also necessary to train civil society such as our lawyers, and other influential members. This will be a focus of ours in the next year. We need to insure that citizens have the right to confer peacefully and to public debate between the secular movement and the Islamists. It is crucial to maintain this peaceful, healthy type of debate and discussion.

We are in a position where we have to accomplish in our region in just a few decades what Europe and the United States have accomplished in centuries. In just one decade we have witnessed the reform of the Family Code in Morocco, then the Arab Spring, which spread across our region and called for a new constitution and now the third commission. We are on our way and in the meantime there is still more work to be done.

JB: As Europe has clamped down on border security, Morocco has become a de facto residence for migrants. Earlier in 2015, the country adopted major policy shifts in regard to migrants and refugees. How many of these refugees are marginalized women and children and what are the country’s future plans for aiding refugees?

DEY: In 2013, we published reports asking the government to adopt new policies towards migrants and refugees. The Moroccan government made the new policy. The first step of this policy was to give legal residence to refugees and immigrants, many of which are women and children. We had 33,000 immigrants asking for legal residence, and 92 percent will have this legal residence. There are two drafts now, one on human trafficking and the other about refugees that are now in the parliament. The migrant NGOs are now acting in the legal framework because migrants and refugees must also be part of the integration policy.

The main challenge for our country is the existing social and economic challenges within our current population. More than 60 percent of our population is under 25 years old and many young Moroccans are asking for work and also for homes. The challenge is to give migrants a place to live and work within this context as well. There are a lot of projects now – some are helped by international NGOs and European governments such as France, Spain and the Netherlands. We need more help from the international partners. If we succeed we will be the only country in Africa to integrate refugees and immigrants, making us a model of best practice for other countries in our region. We can also help Europe in dealing with the current crisis.

JB: 2015 also saw the review of a controversial abortion law in Morocco that not only proposed reforms but also increased education for women and girls that will assist in protecting them from domestic violence and workplace abuse. You were personally asked to provide an assessment of the country’s abortion laws. What were your findings and what is the current status of these reforms?

DEY: This is a bit of a paradox because in some cases abortion is permitted, mainly when the life of the mother is in danger or in rape cases. The landscape is changing as young Moroccans are engaging in sex and some of the women are ending up pregnant. This falls on the negative end of society, as the girls are alone and pregnant. Currently, there is a lot of hypocrisy and lots of illegal abortions. On our part we received 79 memorandums and reports from civil society – a majority of which were in favor of reform while some were against it. Those who are against it have the same arguments as the pro-life movement in the United States. They assert that abortion is a religious Islamic issue so that their argument differentiates from the pro-life movement in the United States, but when you look at the arguments, they are the same.

The Minister of Health and Minister of Justice have been asked to work together on a reform. We don’t yet know what will be the result of this discussion between the two ministers, but from my point of view the issue will be about how to define the health of the mother.

The problem is the international health organizations give a broader definition of health that includes social conditions. In the point of view of the conservative politicians, the health of the woman does not need to include social and psychological conditions. So it is important that we define the health of the woman.

We are noticing in Morocco and in other close nations silent revolutions in regard to women’s rights due to the population being urban, young and connected. 51 percent of Moroccans are under 25 years of age and 55 percent of Moroccans are living in cities while there are 7 million Moroccans on the Internet. Each year we have 180,000 new Moroccans asking for jobs in addition to thousands of NGOs asking for democracy in civil society. This is really shaping such sensitive debates.

JB: You were active in politics in Morocco in the 1970’s during a tumultuous time before going into exile in France for more than three decades. What does your position with CNDH mean to you given your history of experiencing and witnessing human rights violations?

DEY: In 1977 I was sentenced to life in prison as a human rights defender. Lots of people were sentenced then and I became exiled in France where I lived for more than 30 years.

In my life I had two moments that were quite important for me: Before the reform of the Family Code we had two huge demonstrations in Morocco. One was in Casablanca against the reform and the other was in Rabat in favor of the reform. I thought to myself that maybe Morocco was now ready for democracy because we are discussing these sensitive issues. In our society the rights of women is one of the most sensitive.

The other moment was the third commission. I returned to Morocco in 2004 when the King and others asked me to be a member of this third commission. We allowed victims to speak and also had lots of petitions to guarantee better human rights relations. I think we are trying to implement our dreams. Sometimes the process of reforms can be perceived negatively but in the end we can hope for a better country. We can do this by maintaining a healthy public debate field. Still CNDH is the only third commission in the Islamic world and the fifth one in Africa.

See Driss El Yazami’s interview on “Charlie Rose” (July 2015).

Additional Reports:

Gender Equality and Parity in Morocco: Preserving and Implementing the Aims and Objectives of the Constitution , CNDH (pdf)

The Feminization of Public Space: Women’s Activism, the Family Law, and Social Change in Morocco, Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies (pdf)

The Status of Women in the Middle East and North Africa (SWMENA) Project – Focus on Morocco (pdf)

Driss El Yazami is Chairman of President of Morocco’s National Council on Human Rights (CNDH). El Yazami was appointed by His Majesty the King to chair the National Human Rights Council, on March 3rd, 2011. He was born in 1952, in Fez. He is a graduate of the Paris-based Centre de formation et de perfectionnement des journalists. He was member of the Advisory Council on Human Rights (CCDH), the Equity and Reconciliation Commission (Moroccan truth commission) and the board of the Three Cultures Foundation (Spain). He is the Director of Générique, an association specialized in the history of foreigners and immigration in France, and chief editor of the Migrance Journal.

Mr. El Yazami, is a former Vice-President of the French League of Human Rights (LDH), former Secretary General of the International Federation of Human Rights (FIDH) and former member of the Executive Committee of the Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Network. Since 2004, he has been president of the Euro-Mediterranean Foundation of Support to Human Rights Defenders and member of the board of the Cité nationale de l’histoire de l’immigration in France (museum of immigration history). Mr. El Yazami is co-director of the film “France, terre d’Islam ?” (France, land of Islam?) in 1984. He was in charge of several exhibitions: – “France of foreigners, France of freedoms” (Marseille, Paris, Orléans, Strasbourg, 1989-1992); – “In the mirror of the other, immigration in France and Germany” (Frankfurt, May 1993); – “Generations, a century of history of Maghrebians in France (Lyon & Paris – 2009).

He co-authored several works:

– “For Human Rights” (French and English – Syros-Artis, Paris, 1989);

– “Les étrangers en France, guide des sources d’archives publiques et privées” (XIXè-XXè siècles);

– “Le Paris Arabe” (La Découverte – 2003);

– “Générations” (Gallimard, 2009).

Mr. El Yazami drafted (with Remy Schwartz) a report on the establishment of a national centre for the history and culture of immigration, submitted in November 2001 to the French Prime Minister. He published several articles in the French-speaking press (Sans frontières, Baraka, Tumulte, Le Point, Libération, Différences, Projet, Migrations société, la Revue des revues, Hommes et Migrations, Vu de gauche, Homme et libertés, Etudes, Migrance).

Mr. El Yazami was awarded the Legion of Honor (knight grade) of the French Republic, on July 14th, 2010.

______________________

WNN Interim Executive Editor Jessica Buchleitner is on the Board of Directors for Women’s Intercultural Network, a United Nations ECOSOC consultative non-governmental organization. She has served as an NGO delegate to the annual sessions of the UN Commission on the Status of Women for the last four years reporting on various NGO initiatives around the world via the internet and social media. She is also the author of the 50 Women Anthology Series–a two book series of personal stories told by 50 different women from 30 countries highlighting their unique experiences of navigating and overcoming obstacles including political, cultural and societal issues, armed conflict, gender based violence, immigration, health afflictions and business ventures.

______________________

Recognized by UNESCO for ‘Professional Journalistic Standards and Code of Ethics” WNN began in 2005 as a solo blogger’s project by WNN founder Lys Anzia. Today it brings news stories on women from 5+ global regions to the attention of international ‘change-makers’ including the United Nations and over 600 NGO affiliates and United Nations agencies.