The Economist

Middle East & Africa

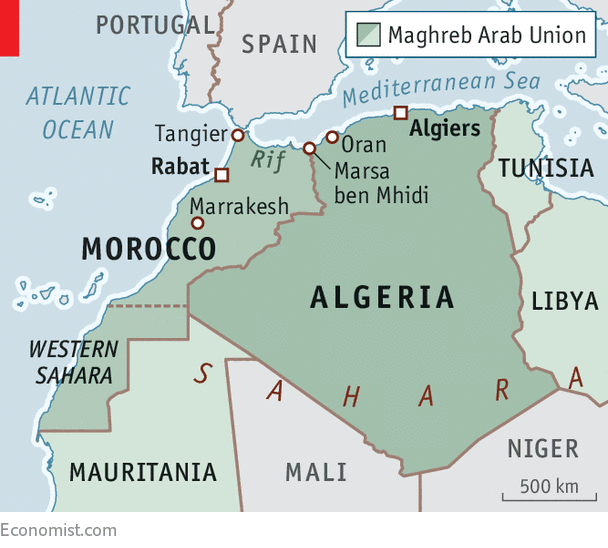

Marsa Ben Mhidi

Fences make neighbours poorer.

Had Algeria and Morocco honoured their agreement back in 1989 to form an economic union, along with Tunisia, Libya and Mauritania, they would be among the Middle East’s largest economies. Their poor border regions would be booming crossroads. Over the decade to 2015, reckons the World Bank, their two economies would each have almost have doubled in size.

Instead, Algeria grew only by 33% and Morocco by 37%, as both governments instead reinforced their barricades. Their north-west corner of Africa remains “the most separated region on the continent”, says Adel Hamaizia, an Algerian economist. While sub-Saharan countries agree common currencies and trade zones, Algeria digs deeper ditches. Morocco revamps its berms and renews its razor wire. Concrete walls rise on both sides. Frustrated families shout greetings across the divide. Tantalisingly, both have built hundreds of kilometres of east-west highways which stop short of their common border.

Islamic empires once spanned the Maghreb, the land of the setting sun, as Arabs term north-western Africa. Both countries share a common history, cuisine, architecture, strand of Islam and an Arabic dialect mashed with Berber and French. But in 1957 colonial French generals erected an electrified barrier, the Morice Line, along the border to keep out arms-traffickers and guerrillas based in newly independent Morocco. Bar five paltry years in between, the border has been closed ever since. In 1963 the two countries fought a brief war. Skirmishes are now rare, but fighting words are common. Algerian republicans deride Morocco’s monarch as feudal, and because of the kingdom’s land-grab of Western Sahara call him the world’s last colonial ruler. Their neighbours cannot help sniggering at Algeria’s latest prime minister, whose name, Tebboune, is Moroccan slang for “vagina”.

Their prospects should be brighter. Both countries have largely avoided the upheavals of the Arab spring. They are almost homogeneously Sunni, free of the region’s sectarian divides. They have the advantage of cheap labour, and offer Europe a bridge to Africa. Algeria has had the edge. It produces copious oil and gas. And it developed a programme of mass industrialisation and agrarian reform after independence, while King Hassan II, who died in 1999, preserved his ancient kingdom like a museum. Algerians spend twice as long in school as Moroccans, and with so much oil, they earn almost twice as much.

Yet Morocco is catching up fast, thanks to its greater economic openness under Hassan’s son, Muhammad VI. The kingdom ranks 68th on the World Bank’s measure for ease of doing business—88 places above Algeria. Exporting goods from Algeria takes six times as long as from Morocco, and costs almost four times as much. Algerian businessmen complain that centralisation, corruption and red tape have crushed local production. Investment is deterred by a law that limits foreign shareholders to 49% of any concern. Look at Renault, they say. Its production line in Tangiers, in Northern Morocco, is the largest car manufacturer in Africa to be sourced from locally made parts. But its plant in Oran, Algeria’s second city, is little more than an assembly line. Algeria’s beaches can rival Morocco’s for beauty. The coves at Marsa ben Mhidi next to its sandbank with Morocco are enchanting. But tourism on its coast remains state-run and spartan, while Morocco’s are considered some of Europe’s premier escapes.

The time was when smuggling at least provided Algerians near the border with a living. Trucks and donkeys hauled subsidised basics like fuel, flour and sugar to Morocco, and returned with hashish from Morocco’s mountainous Rif. But the latest fortifications have put paid to that. Young men who once plied the routes now fill the mosques with their frustration. Unfinished villas line the roads, abandoned. Officials say the new defences will keep out the drug barons and the risk of a spillover of Morocco’s growing Berber unrest. But locals suspect that at a time of falling oil revenues, the army is simply diversifying its revenues by hogging the smugglers’ take. For $80, they say, soldiers will open the gates of army border crossings at night to those without papers.

For five brief years it was all so different. In 1989 both countries removed visa controls as part of a new Maghreb Arab Union. Trade moved freely. Algerians went west on holiday. The two countries parked their squabble over Western Sahara. Then in 1994 a bomb went off in Marrakesh, and King Hassan, nervous that the civil war in Algeria was heading his way, accused Algeria of involvement and chased out its nationals. Algeria’s generals responded by closing their borders, battening down the edges, and retreating into huffy isolation. As with the Gulf Co-operation Council, another trading bloc that has failed to deliver at the other end of the Arab world, practice rarely matches fraternal ideals.

This article appeared in the Middle East and Africa section of the print edition under the headline “Open Sesame”.