National geographic Traveller

By Pól Ó Conghaile

From the labyrinthine Medina of Fez, and the sparkling blue city of Chefchaouen to the mysterious holy town of Moulay Idriss — if you want to get to know Morocco, take a road trip in low season, and get talking to the locals

I’m pinned to the floor of a centuries-old hammam in the foothills of Mount Zerhoun. A bald and bearded attendant in shorts is holding me down like a toddler, scrubbing my skin with a bristly kessa (exfoliating glove) and rinsing the soap off with sloshing buckets of hot water. Just when I think we’re done, he starts stretching me into positions that would make an MMA (mixed martial arts) fighter blush. At one point, my spine pops, chiropractor-style. A steaming group of local men and boys, washing themselves in the small chamber, observe with glee.

If I’d asked for Morocco like a local, this would’ve been the moment I got it. The hammam lies underground in the holy town of Moulay Idriss, northern Morocco. Its chambers are heated by burning thick chunks of aromatic olive wood. The scrub-down peels away embarrassing amounts of dead skin, leaving me the colour of smoked salmon. Steam continues to rise from my head as I return through the medina alleyways to my homestay. It feels like a hazing ritual is complete; that momentarily, this bruising baptism has made me part of the village.

Forget camels and carpets. I’ve come to Morocco in the off-season, seeking to dive deeper than sand dunes and sun resorts. I’d flown into Marrakech, but didn’t stay long. The following morning, I rose early and struck out with a guide and driver towards the Atlas Mountains, starting an itinerary that would also include the hive-like Medina of Fez and the blue-washed walls of Chefchaouen. It’s winter, and tourism is barely a trickle.

“If you want fresh news in Morocco, you need to talk to two people,” says Majid Rouijel, my guide in Moulay Idriss. “The baker and the barber.”

Majid is a honey-voiced local man, born and bred in the tangled-twine alleyways of this hill town (“I spent five years working in insurance in Casablanca,” he tells me. “I didn’t like it. I did an about-turn.”) Majid wears a creamy djellaba (the long, hooded cloak traditionally worn by Moroccans) and seems to know every single soul we pass. When we find the baker, he’s sitting watching a tiny TV perched among shelves loaded with bread. Many families make their own mix in the morning and bring it here for baking, Majid explains. “If a person who usually brings two loaves comes in with four, then something is going on,” he winks.

My walk with Majid is magical because it is so ordinary. Moulay Idriss is a holy place, named for (and home to the remains of) the Prophet Muhammad’s great-grandson. Every August, a religious festival packs out the town, with pilgrims dancing in the streets. It’s just a few miles from the ancient Roman ruins of Volubilis, but few Westerners get this far — in fact, non-Muslims weren’t even allowed to stay overnight until 2005. We see a tailor, twirling threads together from an old nail outside his shop. We listen to the call to prayer, and stand aside to let a young man riding a donkey while engrossed in his smartphone go past. We chat about Islam, Morocco’s young population, its European flavours. ‘Bonjour’ is a common greeting here.

At one point, Majid pauses by a studded townhouse door. He points out its modesty, the lack of frills, and hinges containing the Hand of Fatima to ward off the evil eye. Medina houses rarely give much away about who or what lies within, he says. “You never really know until you step inside.”

Luckily, I get to do just that at La Colombe Blanche, a modest riad converted to a guesthouse by Mohamed Zaimi and his wife. That night, we chat in the kitchen as a couscous, chicken and chickpea stew steams and taktouka (a salad of chopped tomatoes and peppers) simmers on the stove. “Moroccan bread is one-day bread,” Mohamed says, when I describe my visit to the baker. “You can’t have it the next day. We like things fresh and in season.” When dinner is ready, we gather around a table surrounded by mosaic tiles, tucking into a hearty feast, followed by a plate of fresh oranges with stems and leaves attached.

After the meal, Mohamed confers with my guide. “Would you like to go where we’re going?” they ask. “Where’s that?” I ask. “The hammam. We’re going for a bath.”

Hamid Filali, a coppersmith at work in the Medina of Fez. Image: Pól Ó Conghaile

It was back in Fez that I’d first asked to meet the owner of a riad (traditional Moroccan house arranged around a courtyard). Mohamed Merri, my guide and translator, took me to Rachid Azami’s home — a 200-year-old building just inside the medina walls. Several generations of Rachid’s family used to live here, he told us over a cup of sweet mint tea, but in recent years they’d converted it into a guesthouse, and had just finished developing another — a ritzier riad just a short walk away. True to Moroccan form, we were soon touring Riad Marjana, with its sparkling tilework, artisan-crafted wood carvings, glittering pool and lush cushions and drapes. The epitome of exotic Moroccan luxury — all it needed was floating flower petals.

“You can go to a hotel anywhere,” Rachid said, proudly posing for a photograph. “But in a riad, you get to feel history as well as see and hear it.”

Bit by bit, my sense of Morocco was filling out. Holidaymakers have been warier of North Africa since the Arab Spring and recent terror attacks, but the Moroccans I spoke to were keen to distinguish their country — as a gateway between East and West, a place with Mediterranean and Atlantic coasts, rich in Arabic and Berber heritage, but also with French, Andalucian, Jewish and other threads of influence. Of course, there are niggles — jarring clashes of poverty and wealth, litter in the countryside, Morocco’s infamous faux guides, and the need for a thick skin in souks (particularly for women). Common sense, regular tea breaks and a firm ‘no, shukran’ (no, thanks) should help you keep your cool, however.

The drive from Marrakech to Fez takes nine hours, with stops. From there, it’s almost four hours to Chefchaouen, 3.5 hours looping back to Moulay Idriss and another three to Casablanca. All bum-numbing, but fascinating. The dusty, ochre-tinted outskirts of Marrakech give way to a landscape dotted with olive farms and shepherds tending flocks. In Azrou, storks nest atop of a minaret. In M’Rirt, a man walks an ostrich down the street. Banged-up old Mercs, Peugeots and Renaults trundle along and roadside shacks are commonplace, with fresh flanks of mutton and beef hanging in the open air. We stop at one, ordering a few chops to have grilled over charcoal at the cafe next door.

“My father did this,” the butcher tells me, thwacking the meat so hard with his cleaver it sends specks of bone into the air. His belly is big; his yellowing teeth looking like the last pieces on a chessboard. But he speaks almost perfect English. I ask about the sprigs of mint and coriander tied to the cuts beside us. “The meat is killed and we refrigerate it for about two days,” he says. “Then it’s ready. Moroccans don’t like frozen meat.”

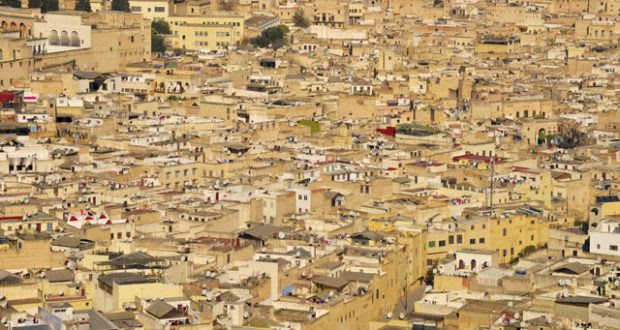

Within a few minutes, the mutton is grilled and delivered — along with a loaf of bread, tomatoes and onions — to our table. We sprinkle pinches of salt and cumin over the meat. It’s messy, finger-lickin’ Moroccan street food. In Fez itself, all roads lead to Fez el Bali (listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site under the name Medina of Fez). Dating from the ninth century (‘New’ Fez followed in the 14th century, with a later wave of French development completing the mix), the medina is reputedly one of the largest car-free urban zones in the world. “Inside are 9,000 streets and 40,000 dead ends,” quips my guide, Ghazali Hicham, who grew up and went to school inside this maze. “It’s the biggest labyrinth on the planet.”

Fez, a former capital of Morocco, has other attractions — not least the Royal Palace; a busy Jewish Quarter where we stop to taste sfenj (fried Moroccan doughnuts); and Art Naji, where I watch artisans shape, paint and bake their meticulous mosaic tiles and ceramics. But its medina is the highlight. Viewed from the surrounding hills, the old quarter is a dead ringer for Granada’s Albaicín — albeit much, much larger; its chino-coloured houses stacked so densely you can’t see the alleys between them. Inside, it’s like stepping into medieval times.

Two or three turns is all it takes for me to get lost. “What about that one?” Ghazali smiles, gesturing to the dimly-lit laneway ahead. “Is it a way out, or a dead end?” Gradually, we wind our way towards the markets. I marvel at the blue hands of a clothes dyer; at a camel’s head suspended from a hook; at men washing hides in the great colourful vats of a tannery — overhead, tourists watch from the balconies of leather shops, holding mint under their noses to ward off the stink.

If Djemaa-el-Fna, in Marrakech, can seem like a carnival, this is pure street theatre. Wasps buzz around sticky treats. Antique shops glimmer. Keyhole doors lead to centuries-old schools and mosques. You might catch the whiff of goat’s cheese, or hear the whirr of a loom. School kids brush by with satchels; men wander past, Jedi-like in their djellabas. Every now and then, there’s a cry of ‘balak!’ (‘watch out!’) as a worker barges by with a cart or a mule. There are hidden riads and restaurants like Cafe Clock — established by Mike Richardson, the former maître d’ of London’s The Wolseley and The Ivy (I stop by, and am persuaded to try the camel burger). All of human life seems packed into this ancient honeycomb.

On Place Seffarine, coppersmiths hammer pots and pans, as they have done for centuries. I ask one of them, Hamid Filali, what his apprenticeship was like. “The kiss was as sweet as the bite was tough,” he replies cryptically, beating out the metal to a hypnotic rhythm — bam-bam-ba-bam, bam-bam-ba-bam…

I feel like a time traveller, but wonder how long it’ll all last. Ghazali’s father was a shoemaker here, but he didn’t want his children to be. “It was just too hard a life,” his son tells me.

Chefchaouen, three hours north in the Rif Mountains, is similarly exotic. The old town here is an Instagramer’s paradise, almost completely painted blue. Why? There are several theories — one that the limewash helps keep mosquitoes away; another that it originated with Jewish residents, who believed the colour echoed the sky, encouraging a more spiritual life. Whatever the origin, it’s enchanting — Morocco’s ‘Blue Pearl’ is like the pueblos blancos of Andalucia taken to another, almost psychedelic level. Brightly coloured flower pots, shady vines, lazing cats, bunches of mint and hanging rugs punctuate the backdrop.

Of course, Chefchaouen is no longer really a ‘secret’ — in warmer months, Moroccan visitors and travellers taking the ferry from Spain clog the streets (there’s no shortage of souvenir shops or laminated menus). But visiting in low season skips both the heat and the crowds — as does getting up early.

At 5.30am, I’m woken by the twin alarms of cocks crowing outside the Dar Echchaouenhotel and calls to prayer moaning from the minarets. I grab a quick breakfast, before hiking a 20-minute trail up a mountain behind the hotel for a view over the town. ‘Chaouen’, as locals call it, takes its name from the Berber word for ‘horns’, sitting as it does between two peaks. Walking back down through the medina, I chance on a Thursday market where women from Berber villages have laid their wares out on blankets — tiny turnips (“very small, but very delicious,” as Mohamed says) and milk in reclaimed plastic vessels. Some wear traditional straw hats and red-and-white-striped aprons. I ask what kind of milk they’re selling. “Moo!” replies an older lady, and we share a chuckle. With Mohamed translating, we swap little details about our children and the weather, and we exchange blessings. As we take our leave, I ask one of the ladies if I can take her photo. She demurs. “Mafi mouchkila,” I say — using one of the most adaptable Arabic phrases I’ve learned on my trip. “No problem.”

One place the women’s turnips won’t end up is in the belly of Mustafa Bakkali, whom I find flitting between the kitchen and dining rooms of Bab Ssour. Three years ago, this intimate clutch of rooms — which we enter via a small grocery shop — was a family home. Today, the same food is being cooked by the same women in the same kitchen, only now it’s served to a mix of locals and tourists sitting elbow-to-elbow in a restaurant. Voices snap from a kitchen visible through an arched gap in the wall (“It sounds like they’re arguing, but they couldn’t be happier,” Mustafa says), and I gobble up a goat tagine that arrives sizzling in a skillet and costs all of 35 dirham (£2.70). “It’s the same food we eat at home,” Mustafa adds. I wonder which dish is his favourite. “I eat it all,” he replies with impressive gesticulations for such a small space. “Except turnip.”

After a week exploring the cities, towns and villages of the north, driving into Casablanca feels like a return to the real world. Snarling traffic marks the entrance to Morocco’s biggest city, and any romantic notions based on the 1942 movie are quickly scotched (there’s a replica Rick’s Bar, a gin lounge and restaurant dating from 2004, but the Humphrey Bogart classic was shot on a Hollywood sound stage). I stay for a night, moseying around the medina, Hassan II Mosque, corniche and art deco strips, stopping for a final mint tea, poured from a silver teapot near Place 16 Novembre.

It’s all well and good, but I’m surprised how quickly I begin to pine for Fez, Moulay Idriss and Chefchaouen. “Hello, friend! Bonjour!” a hustler hisses. “Berber market? Berber market, this way!”

“No, shukran,” I reply.

ESSENTIALS

Getting there & around

Royal Air Maroc flies from Heathrow to Casablanca. TAP Portugal also flies via Lisbon; as does Iberia via Madrid. A range of airlines, including British Airways, Ryanairand EasyJet, fly from the UK to Marrakech.

Average flight time: 3h 15m.

Trains, buses, and grands (collective) and petits (local) taxis cover most of Morocco. Self-driving (on the right) is an option, with regular police checkpoints and a decent network of motorways.

When to go

Avoid the peak-season (July-September) heat and mayhem; spring and autumn are less crowded with fresher weather. Winter can be cold, but you’ll be one of very few tourists. Ramadan is 16 May-14 June.

More info

visitmorocco.com

How to do it

Intrepid Travel offers a nine-day North Morocco Adventure, starting from Casablanca and travelling to Moulay Idriss, Fez, Chefchaouen and Tangier before finishing in Marrakech. From £530 per person, including accommodation, transport, guides, activities and selected meals (flights extra).

Published in the May 2017 issue of National Geographic Traveller (UK)