MOROCCO NEWS BOARD

Yael Miller

For over three decades, one of the major issues preventing Maghreb unity has been the Western Sahara conflict. Analysis of the conflict has always emphasized the need to include The Polisario Front (or POLISARIO) in any peace plan or vision. The Polisario Front, a Saharawi separatist group, has fought for Western Sahara’s independence from Morocco since the early 1970s.

Much of the group is located in Algeria, where it enjoys support and refuge; in addition, tens of thousands of Saharawis live in camps located in Tindouf, Algeria. The Western Sahara conflict has often mirrored international relations between Algeria and Morocco by serving as a proxy for these two regional powers. Throughout its existence, the Polisario Front has acted in the context of broader regional issues or interests gradually gaining in notoriety. Its influence on regional affairs was greatest during the 1980s. However, after the 1970s and until the 2000s, it remained ineffective in bringing its cause of an independent Saharawi state as viable solution to the conflict. At present, the Polisario Front no longer represents the Sahrawi people, as its unity has deteriorated; a negotiated settlement of the Western Sahara issue does not therefore need the inclusion of the Polisario Front.

Background

The Polisario Front “began in the 1970s almost from a standing start and under the most unenviable of conditions” (Pazzanita, 1994, p.270). The thousands of refugee Saharawis that arrived in Algeria at the time lacked not only possessions, but also a cadre of educated personnel that could spread the news of their plight (270)., the Polisario Front itself began with limited resources as well as limited capabilities. The limited resources would then affect both the way the group was viewed by Saharawis as well as international perception; for many years, the group was viewed as an “underdog” in the battle for Western Sahara. Although the group was, at the beginning, an anti-colonial movement against Spain, which at the time had oppressed other efforts for independence (Zunes, 1987, p.37), the group later transitioned to fight primarily against Morocco, after Morocco took over parts of Western Sahara upon Spain’s exit. The Front aims to wrest control of Western Sahara from Morocco, allow the refugees living in Algeria to return, and establish a new, independent government in the country.

The POLISARIO has been linked to various ideological movements, including Marxism and Islamism. Pro-POLISARIO scholars such as Zunes attribute the group to a non-ideology, (Zunes, 1987, 39) and “a coalition of Sahrawi nationalist political tendencies, spanning Western notions of a Left-Right, progressive-conservative spectrum” (Zunes and Mundy, 2010, p.115). The Polisario’s actions must thus be analyzed within a multifaceted ideological context and attributed to a variety of actors within the group itself with their main goal being an independent Saharawi state.

1970s-1980s

The late 1970s and the early 1980s were the apex of the Polisario’s diplomatic work. Polisario viewed itself as a member of a larger group of Arab revolutions throughout the Levant and North Africa and of democratic movements in general (Hodges, 193, p.164). This propelled it to seek the support of other developing nations, like in Latin America and the broader Middle East fighting against a perceived larger adversary. Its efforts were so successful that, in 1977, “Polisario [was] forging a growing alliance with the masses of Mauretania and Morocco” (Essack, 1977, p.1734). While perhaps the growing alliances may not have described all the Moroccan population, for example, and their support for events like the Green March in Morocco, which supported Morocco’s possession of Western Sahara, his comment should not be taken in isolation; indeed, the Polisario Front was successful in their recruitment of sympathetic nations and peoples around the globe at the time, to the extent that that even within Morocco and Mauritania, in the middle of full-fledged conflict, the Polisario Front was making inroads in popular sympathy. Its efforts also espoused diplomacy. As Pazzanita writes, “from the beginning of the Western Sahara conflict to 1985, [this phase] marked a successful effort to garner support from sympathetic African, Asian, and Latin American regimes, a process which culminated, in November 1984 in the unopposed seating of the Saharawi Republic’s delegation as a full member of the O.A.U. [Organization of African Unity]” (Pazzanita, 1994, p. 270).

The Polisario Front’s diplomatic efforts would later influence regional politics. Muammar Qaddafi, acting to support nationalist movements throughout the world, gave rhetorical backing to the Polisario Front and caused ripples in the Organization of African Unity. At first, “Gaddafi alienated a number of moderate African states by helping to engineer the recognition of the Polisario guerrilla movement”(Time, 1982); Gaddafi’s support would prove to have regional ramifications that would isolate Morocco and help the POLISARIO move up the diplomatic ladder. By 1982, a large number of states—seventy—formally recognized the S.A.D.R. or the Polisario’s proposed independent state (Zunes, 1987). While the formal alliances were mostly with developing countries, the Polisario Front succeeded in isolating Morocco and winning the support of third-world governments at the time and acted as a participating body in the OAU. In 1984, for the first time, the a majority in the Organization for African Unity to seat the Polisario Front as a full member” (Time, p.93) The isolation Morocco experienced was soon felt in the ramifications of the OAU’s actions, and further shows The Polisario Front’s regional influence.

The Front was also active in supporting other organizations and peoples engaged in similar struggles of the time, including the ANC in South Africa, the Palestinian people, and SWAPO in Namibia (Zunes, 1987, p.44). Essentially, the Polisario Front acted in support of broader decolonization concerns and interests in order to garner more support in the international arena.

The Current Security Situation in North Africa/Sahel

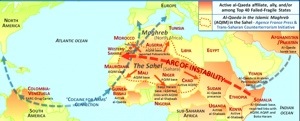

Analysts have increasingly pointed to the geographic areas of North Africa and the Sahel as sources of instability. The combination of fragile states, weak governments, demographic changes and corruption have taken their toll on the peoples in these areas: “…the fragility of the majority of Sahel states and regional instability perpetuate conditions that breed insecurity: rapid population growth (except in the Maghreb, which is going through a demographic transition), corruption, endemic poverty, illiteracy, and incessant conflict, resulting in displaced populations (refugees) and illegal migration” (2009, p. 1). The situation in the Sahel and North Africa has led to the flourishing of illicit activities, including terrorism, in the region, oftentimes via traditional networks or the takeover of areas without much state control (2009), which is bolstered by weak rule of law in the region.

Cedric Jourde explains, “take the case of illicit trafficking across the Sahel, which involves goods ranging from cigarettes and stolen cars to drugs, weapons, and persons. This has evolved into a broad and interconnected ‘economy of insecurity’ (2011, p.2) that includes tribes across the region (2011). Criminal networks, in the 21st century, have generally evolved through fluid network structures which lead to established criminal groups corrupting leaders and citizens in a given area; often times, they will cooperate with insurgent groups and infiltrate banks, businesses, and organizations (Williams, 2001, p.61). These networks then become an integral part of the criminal structure and can easily expand into other geographic areas. These geographical areas then become a part of the criminal system through the criminals’ attachment to them (Ammour, 2009).

Terrorism, in the form of al Qaeda operations, is also thriving. Because of the lawlessness of these regions, Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) has found a safe haven in the Sahel and North Africa. The group, an alliance of Sunni Islamist groups, “appeals to disaffected youth and sustains itself by smuggling drugs and other goods and by kidnapping people for ransom” (The Daily Star, 2009). The group is only growing in power and influence. In the past ten years, AQIM has increased its attacks about 500 percent (Alexander, 2012, p. 4). AQIM takes advantage of the instability of the region and the weak governing states to promote its own illicit activities.

(Image taken from Alexander, 2012) AQIM and its affiliates are active throughout the Sahel and North Africa.

Sahrawis are particularly susceptible to AQIM’s claims: “Prospects for youth stuck for years in Sahrawi refugee camps are gloomy. Understandably, some may be tempted by more adventurous business-related or ideological alternatives” (2011, p. 4). It is precisely this dangerous mix of ungoverned spaces, poverty, and criminal and terrorist networks that provides ample breeding ground for corruption with the Sahrawi population, including the Polisario Front.

Current Issues- Criminal Activity

Unfortunately, “For years now, Polisario leaders and their Algerian backers have categorically denied that the Sahrawis, placed under their tight control, engage in any mercenary or militant activity…” (Boukhars, 2010, p.7). While Sahrawis, Algerians, and members of the Polisario Front have all denied their connection with criminal activity, evidence does point contrary to their claim. The Sahel and Northern Africa are notorious for drug and human trafficking, and the Polisario Front is involved in both, according to dozens of reports from the region. The situation in many of the refugee camps is dire, and, as ex-Polisario police chief Mustafa Salma Uld Sidi Mouloud explained, “The situation is grave for the youth who are marginalized, and I feel that the camps are fertile grounds for Islamic fundamentalist groups and drug traffickers. The young Saharawis are getting caught up in these illicit activities and it is costing them their lives” (Rubin, 2011, n.pag.). Young Sahrawis are lured in by economic incentives promoted by the Islamist fundamentalist groups, aligned with the Polisario, which have taken advantage of the blurry security situation in the Western Sahara and the Sahel for nefarious purposes. More precisely, “The Polisario is notorious for exploiting the instability in the Sahel to incubate its own drug trafficking network. The region has morphed into a producer of and transit point for cocaine originating in Latin America and destined for Europe in order to skirt conventional border control mechanisms” (CSIS, 2010, n.pag.). For Europe and Latin American markets, the North Africa region has become a hub of support for drug trafficking, and the Polisario are intimately associated with the trade. Polisario-controlled points are used in order to facilitate the drug trail: “a study conducted by Altadis (a European tobacco company) revealed that ‘Sahrawis are involved in a vast network of smuggling…using various routes, passing through the Western Sahara to Algeria via Tifariti and Bir Lahlou, oases controlled by the Polisario Front’ (Boukhars, 2010, p. 7). Adding to the chaos, Algerian authorities have turned a blind eye on Polisario activities in many of the Front’s controlled areas. “Time and again over the last few years, members of the Polisario have been implicated in cases of trafficking people who are transiting via Morocco to reach Europe…Moreover, many Sahrawis linked to trading arms, petrol, smuggling cigarettes or spare parts of cars…the impunity which exists in the sub-Sahara area has favoured the development of illicit trade of every variety in the same way that it has contributed to the spread of terrorism in the region” (ESISC, 2008, p. 7). Criminal activity grows easily in Front-controlled areas, due to lawlessness and seeming impunity against prosecution; trade in illicit items has become the norm in the sub-Sahara area, and the Polisario stands at the front and center of these activities.

Polisario as a Source of Expertise for AQIM

The Polisario Front’s involvement in regional issues has gained notoriety in recent years. Unfortunately, as Saidy notes, “it is advisable to view the link between Polisario and terrorism in the Sahel not as Moroccan propaganda but as reality.” (Saidy, 2011, p. 90). While Polisario’s early experiences do not point towards cooperation with Islamist terrorist groups, the connection is emerging as stronger than expected. As well, the Front has been in Al Qaeda’s sights for period of time, and “Endeavors to penetrate the Polisario Front of the Western Sahara have long been on al-Qaeda’s agenda” (Baker, 2010, n.pag.).

Given that the Polisario Front has been given less media attention in recent years, and difficult conditions in refugee camps, perhaps the cooperation between al-Qaeda and the Polisario was inevitable. The relationship first emerged after a GSPC (Algerian Salafist Group for Prayer & Combat, a predecessor to AQIM) attack on a Mauritanian security force base in Lamghiti; the operation was led by Mokhtar Belmokhtar, the future leader of AQIM. The attack, which killed fifteen people, used vehicles that belonged to the Polisario Front (CSIS Transnational Threats, 2010). From 2005, the Polisario has been implicated in several AQIM operations. The group was the subject of major recruitment of AQIM and supported their operations by 2008: the CSIS Transnational Threats newspaper published, “In July 2008, the Algerian dailyEl Khabar confirmed the presence of new recruits arriving from the Western Sahara to AQIM training camps near the border with Mali. Concurrently, the Moroccan press published an article stating that AQIM came to Polisario camps in search of new recruits, estimating that 265 former Polisario fighters joined AQIM” (2010, n.pag.). In 2009, AQIM kidnapped three Spanish humanitarian aid workers in Mauritania; Omar le Sahraoui, a former leader of the Polisario Front, actually conducted the attacks and was arrested and charged with the abduction (CSIS Transnational Threats, 2010, n.pag.); while some speculate that ideological motivation may not have been the strongest factor in Sahraoui’s involvement (rather, his expertise in trafficking may have been the motivation). Nonetheless, in addition to Sahraouis, twenty other Polisario Front members have been arrested for the crime (CSIS Transnational Threats, 2010, n. pag.). The Polisario transitioned relatively quickly from supplying AQIM with vehicles to actually conducting operations for the terrorist organization. AQIM has benefited from the Polisario’s experience in criminal activity, including trafficking and kidnapping, and therefore, a natural partnership has emerged in which AQIM finds utility in Polisario expertise, and therefore implements attacks using Polisario resources.

Polisario Condemned by Regional Security Services

Malian and other regional security services have taken notice of these attacks, and, in December 2010, Malian authorities arrested another six drug traffickers linked with an AQIM-aligned group, all members of the Polisario Front (Boukhars, 2012, p. 6). Algerian security forces arrested ”Sidi Mohamed Mahjoub, a Polisario imam, whose home allegedly contained arms, 20 kilos of explosives, and correspondence with AQIM leader Abd al-Malik Droukde” (Lake, 2011, n.pag.). The discovery of a massive cache of explosives as well as the correspondence with an AQIM leader bodes unwell for the future of the Polisario Front as a legitimate organization. Moroccan officials estimate seventy-five arrests of Polisario Front members in Al Qaeda operations (Lake, 2011, n.pag.). While indeed Morocco may prove a biased source, and may use anti-AQIM operations as an excuse to quash POLISARIO support, its arrests, viewed within the context of broader regional arrests, indicates more credibility to an AQIM-Polisario link than at first glance.

Even Spain, once a neutral party, has spoken out against the Polisario. While previously Spain had attempted to keep a balanced stance to the conflict for many years (Cemboro, 2010, n.pag.), in light of recent events concerning the Polisario, Spain has begun to speak out. In 2011, Spain called for a UN committee to reevaluate the security situation in Polisario-controlled Tindouf (Al Arabiya, 2011, n.pag.), after the kidnapping of three aid workers, two Spanish and one Italian, in Tindouf. Both Spain and the Polisario’s staunch ally, Algeria, came out fighting to recover the terrorists responsible for the attack. As al-Arabiya wrote at the time, “Algeria has reportedly deployed both ground and air forces in an “urgent” operation along its borders with Mauritania, Mali, Niger, and Libya to prevent the escape of the kidnappers” (2012, n.pag.). As AQIM steps up its attacks in North Africa and advances operations with the Front, POLISARIO may soon see itself become an international pariah for its involvement in regional affairs. Many of the states surrounding the Front are fast losing faith in the Polisario Front. RFI wrote in December 2011:

“Bamako ne mâche pas ses mots : plus question d’accepter la violation de son territoire par les militaires du Front Polisario. Sans autorisation, ces derniers, avec des armes de guerre, sont récemment venus dans le nord du Mali. Sur place, ils ont tué un homme, et enlevés au moins trois autres. Tous, étaient accusés d’avoir participé à l’enlèvement fin octobre de trois humanitaires européens dans le quartier général du mouvement indépendantiste.”

While the Malian government may have its hands full at present, the Polisario will soon run out of political capital, should its activities in regional terrorism continue. The Polisario’s complicity in terrorist activities can no longer be ignored if the Western Sahara conflict is going to be solved.

The Polisario as a Far Cry from Its Previous Organization

The UN Convention Against Transnational Crime defines “Organized criminal group” as “a structured group of three or more persons, existing for a period of time and acting in concert with the aim of committing one or more serious crimes or offences established in accordance with this Convention, in order to obtain, directly or indirectly, a financial or other material benefit” (UN Convention, 2000, Article 2). The Polisario Front fits the category.

The Polisario remains only a shadow of its previous self. Its leadership is largely dispersed to other regions, and its international activities as a group are mostly notorious for criminal or terrorist activities, as opposed to being a viable candidate to solve the issue of peace in the Western Sahara. Former Polisario Leader, Hamett Rabani, stated in a recent report to the European Strategic Intelligence Center:

“‘The Polisario is in a situation of failure. The majority of the former fighters has left and has gone back into Mauritanian affairs. Many historic leaders also left. Quite a few young people remain. What can the leadership say to them? What hope can it give them ? None. The movement is at an impasse, and some, in order not to lose all hope, are turning to religion, to God. They no longer expect anything from the chiefs of the Polisario but look for everything from God. God fills the void left by the backward looking leadership of the Polisario.(Moniquet, 2008, p.4)

Hamett Rabani is not the only ex-Polisario member condemning the group. As reported in the Washington Post, Mustafa Salma Uld Sidi Mouloud, ex Polisario police chief, was abducted after he visited Morocco and soon began to repent having joined the group (Rubin, 2011, n.pag.). He explains to Jennifer Rubin, blogging for the Washington Post, that “anyone who leaves the refugee camps without permission of the Polisario Front is considered a traitor who is committing a crime and, according to the Polisario’s penal code, such actions are punishable by ten to 20 years in prison, and this goes for all Saharawis for the last 30 years. When I tried to raise my voice about the Polisario and Algeria’s disregard for human rights, they expelled me” (Rubin, 2011, n.pag.). By limiting Sahrawis in refugee camps in their right of movement, and expelling those who disagree with their harsh laws, the Polisario Front is acting more like a mafia than a political party.

Given the evidence of the Polisario’s recent illegal activities, its previous self is scant to be seen. Stephen Zunes’s article from 1987, writing about the Polisario, demonstrates the evolution of the movement: “Pure ideology appears to be foreign to these traditionally nomadic people who for centuries have rallied around the desire to be free” (1987, p. 39). Indeed, the lack of ideology has now created a group that is simply tied by material interests and rent-seeking. It has created alliances with the most unenviable of characters, which does not bode well for its goals of liberation and independence for Western Sahara. Both tribal and regional leaders have emerged criticizing the Polisario Front’s perceived weight in the region, and have implored the Front’s leaders to listen to the Sahrawis. The Polisario Front no longer has influence in the very country it wishes to “liberate” from Morocco’s grasp. While indeed, those living in the refugee camps may support POLISARIO to a greater extent, analysts can no longer expound upon the Polisario Front’s vast sway in the region of Western Sahara.

Similarly, supporters of the Sahrawi movements are in a quandary, as “the international community has become increasingly alarmed by failed ministates, such as Timor-Leste, and unchecked secessionism. Even the most ardent supporters of the ‘Sahrawi people’ in the West now doubt the viability of a POLISARIO-run state…AU expert studies have demonstrated that a Polisario-run state cannot sustain any other type of economy on its own; industrial and resource development are impossible without reliance on the infrastructure and human resources of Morocco” (Bodansky, 2008, n.pag.). The Polisario Front’s end goal is truly not feasible.

The Polisario front, disjointed and dismembered, as explained above, does not represent the will of the Sahrawi people, and therefore should not be taken into consideration for any future plans. For instance, as Yossef Bodansky wrote, when Polisario Secretary General called for arms in response to UN-sponsored talks with Morocco in 2008 [emphasis mine]:

“The local population, mainly the tribes living in MWS [Moroccan Western Sahara], were clearly alarmed by the call to arms. Hence, tribal leaders led by Himad WaILd [sic] Al-Darwish organized unprecedented demonstrations in southern MWS, near the border with Mauritania. The demonstrators urged the POLISARIO congress to heed to the will of the people they claimed to be representing, reject the armed struggle, accept the Moroccan autonomy plan, and concentrate on the peaceful development of MWS. The protesters also urged the UN to address the issue of the refugees in Tindouf. This was the first time that both prominent regional and tribal leaders as well as the grassroots population openly challenged POLISARIO and its claim to representing the “Sahrawi people” (Bodansky, 2008, n.pag.)

Not only is the Polisario Front inciting violence, but it is also doing so against mass criticism of its actions by its own people. Sahrawis do not view the Polisario as being in-touch with their daily reality and seek a peaceful resolution of the Western Sahara conflict, including accepting Moroccan autonomy plan, as the recent failure of the call to arms demonstrates.

The Case for Autonomy and Potential for Violent Conflict

In July 2011, Morocco set forth a constitution which would ensure decentralization and limited autonomy for Western Sahara: power would slowly be devolved into elected regional councils (Boukhars, 2012, p.16). The process, if accepted, would represent a new beginning for the Western Sahara and help towards a resolution. As Boukhars suggests, “it [the constitutional proposal] has the potential to increase participatory development and government responsiveness. It will also meet one of the main demands of disgruntled Sahrawis: the ability to manage their own affairs” (2012, p. 16). The agreement would provide the Western Sahara with the ability to free itself to a certain degree from Moroccan oversight, and pave the way for autonomy. Eliminating the Polisario Front would help to free Algerian and Moroccan officials as well as Sahrawis themselves to solve the Western Sahara conflict. Jacob Mundy explains that the main reason for deadlock on the issue has been the unwillingness of Morocco, Algeria, and Polisario to make compromises for peace (2007, n.pag.). In light of these recent steps by Morocco to promote autonomy, discussions without the Polisario Front as an added adversary seem to behoove the prospects for peace to a great extent. Morocco may be more favorable to discussions of autonomy and referendum without the Polisario. Considering the Front has targeted Moroccan military facilities and industries in the past and that Moroccan authorities have persecuted the Front and its supporters, it is understandable that negotiations between the two have stalled. However, in order for the prospect of peace to become a reality, the Polisario Front should be left out of possible discussions which will promote compromise between the Moroccan government and the Saharawi people.

For its part, Morocco is not blameless in the Western Sahara issue. It has been condemned by groups like Human Rights Watch of abuses such as arresting non-violent activists and giving the only option of military court to civilians. However, Morocco is still in a relative position of power, compared to the Polisario Front. It currently holds the keys to autonomy or independence, and the Polisario Front is simply an obstacle to peace; they no longer represent the people they claim.

Algeria should recognize the need to withdraw its support from the Polisario Front. Algeria’s backing promotes the group to a level that would be unknown without it. Considering that it currently is allied with the United States and Morocco against terrorism in the Trans-Sahara Counterterrorism Partnership (AFRICOM, n.pag.), Algeria would do well to disassociate itself from the Polisario Front, which is only growing in ties with AQIM. The Front also helps maintain the instability that proves so problematic for fighting terrorism; the longer the Front has Algerian backing, the stronger POLISARIO will become. If Algeria is to keep the funding and alliance with the United States, it would do best to weaken its links with the Polisario Front.

However, although it is possible to exclude the Polisario, it does not mean it will be an easy task. There is a possibility of violence re-erupting should drastic steps be taken to remove the Polisario from negotiations. As early as 2007, Algeria diplomats were “already warning Western governments about the explosive potential of the POLISARIO congress in Ln Tifariti” (Bodansky, 2008, n.pag.). The Polisario Front still owns the autonomy of violence in the region and even if the leadership still seeking political reconciliation tried, it is claimed, “Algiers has indicated that it was not sure the POLISARIO leadership could prevent fringe elements from taking up arms and sparking a wider crisis/war” (Bodansky, 2008, n.pag.). While Algiers may have political motivations of its own, the Polisario’s military capabilities should not be taken lightly. Non-state actors can still have capacity for violence, and it is indeed the fringe elements that could cause a wider conflict, theoretically, “the state holds no monopoly of violence; rather, people retain control over the means of coercion, and it is their threat to revert to violence, should others defect, that supports order along the equilibrium path” (Bates et al, 2002, p.600). The Polisario, in the past, has had numerous military victories over Morocco, and, considering their recent acquaintance with AQIM and their expertise in smuggling, could pose a serious threat.

Conclusion

In the 1970s and 1980s, the Polisario Front was a united group fighting for independence for Western Sahara. It was active in garnering support for its cause and gained the assistance of many developing nations. From joining the Organization for African Unity as a full-fledged member to receiving Muammar Qaddafi’s backing, the group had prominent aid to their cause in the region. The Polisario Front viewed itself in the context of liberation and as part of a wave of nationalism sweeping the globe at the time.

However, the environment in which Western Sahara is located soon grew dangerous. Fragile states combined with weak law enforcement abilities grew in the Sahel and North Africa; the situation in the Western Sahara refugee camps grew more depressing and lifeless. Criminal activity, including trafficking and smuggling, began to spread rampantly in Polisario-controlled areas. In addition, AQIM began activities in North Africa and the Sahel as instability in the region continued. Links between the Polisario and AQIM flourished and Polisario members began providing expertise and materials to AQIM members.

Others in the Western Sahara community began to notice. More and more ex-Polisario members as well as Saharawis themselves began to speak out against the Polisario Front as not representing their needs. Especially in light of recent autonomy plans for the Western Sahara, the Sahrawi’s condemnation of the Polisario Front should be heeded.

The Polisario Front no longer represents a unified actor. They instead act as a criminal organization, aiding in activities such as drug smuggling and allowing illegal movements through the territory they control. Security forces throughout the region have grown increasingly frustrated with the Polisario Front, especially the Front’s relationship with AQIM, an item that will soon come to heads with Western-backed security initiatives in the region.

Therefore, the Polisario Front need not be included in further negotiations. While this may lead to further violence, it is a step that is inevitable. As long as the Polisario Front is involved, there will not be an independent or autonomous Sahrawi state: the Polisario have benefited from their perceived impunity, and now is a ripe time to show the Front that they are not truly unified; rather, they are a group of loosely-related Sahrawis, many of whom are criminals.

References

Al-Qaeda Thrives in the Sahara Deadlock. (2009, April 15). The Daily Star, p. n.pag.. Retrieved April 11, 2012, from the Proquest database.

Alexander, Y. (2012). Terrorism in North, West, and Central Africa: From 9/11 to the Arab Spring. Special Update Report, n/a, 1-25. Retrieved April 10, 2012, from www.potomacinstitute.org

Ammour, L. (2009). An Assessment of Crime Related Risks in the Sahel. NATO-OTAN Research Paper, 63, 1-7.

Bates, R., Greif, A., & Singh, S. (2002). Organizing Violence. The Journal of Conflict Resolution, 46(5), 599-628. Retrieved April 10, 2012, from the EBSCO database.

Bodansky, Y. (2008). POLISARIO and the Algerian Power Struggle, with Itself and the West. Defense and Foreign Affairs Strategic Policy, 1(36), n.pag.. Retrieved April 30, 2012, from the ProQuest database.

Boukhars, A. (2012). Simmering discontent in the Western Sahara. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Cembrero, I. (2011, December 15). Spain favored Morocco’s autonomy plan for Western Sahara. El Pais. Retrieved April 30, 2012, from El Pais

Essaack, K. (1977). Polisario Shows the Way. Economic and Political Weekly, 12(41), 1734-1735. Retrieved April 4, 2012, from the EBSCO database.

Has Spain Switched Gear on the Western Sahara Conflict. (2011, October 25). Al Arabiya. Retrieved April 28, 2012, from www.alarabiya.net

Hodges, T. (1983). Western Sahara: the roots of a desert war. Westport, Conn.: L. Hill.

Jourde, C. (2011). Sifting Through the Layers of Insecurity in the Sahel: The Case of Mauritania. Africa Security Brief, 1(15), 1-7. Retrieved April 30, 2012, from www.africacenter.org

Moniquet, C. (2008). The Polisario Front: A Destabilising Force in the Region that is still Active. ESISC Papers, n/a, 3-19. Retrieved April 4, 2012, from www.esisc.org

Mundy, J. (2007). Autonomy and Intifadah: New Horizons in Western Saharan Nationalism. Review of African Political Economy, 33(108), 255-267.

(2010). AQIM and the Polisario Frente. CSIS Transnational Threats, 3, 2. Retrieved April 30, 2012, from www.csis.org

Pham, J. P. (2011). The Dangerous “Pragmatism” of Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb. Journal of the Middle East and Africa,2(1), 15-29. Retrieved April 4, 2012, from the EBSCO database.

Rubin, J. (n.d.). Right Turn – Exclusive: Ex-Polisario Front police chief tells his story . Blogs & Columns, Blog Directory – The Washington Post. Retrieved May 3, 2012, from http://voices.washingtonpost.com/right-turn/2011/01/exclusive_ex-polisario_front_p.html

Saidy, B. (2011). American Interests in the Western Sahara Conflict. American Foreign Policy Int, 33, 89-92. Retrieved April 4, 2012, from the EBSCO database.

Williams, P. (2001). “Transnational Criminal Networks.” In J. Arquilla and D. Ronfelt (eds). Networks and Netwars: the Future of Terror, Crime, and Militancy. Santa Monica: RAND.

Zoubir, Y., & Benabdallah-Gambier, K. (2005). The United States and the Norht AFrican Imbroglio: Balancing Interests in Algeria, Morocco, and the Western Sahara. Mediterranean Politics, 10(5), 181-202. Retrieved April 4, 2012, from the EBSCO database.

Zunes, S. (1987). Nationalism and Non-Alignment: The Non-Ideology of the Polisario. Africa Today, 34(3), 33-46. Retrieved April 4, 2012, from the JSTOR database.

Zunes, S., & Mundy, J. (2010). Western Sahara: war, nationalism, and conflict irresolution. Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press.

An Angry King Pulls Out. (1984). Time, 124(22), 93.

Failed Summit. (1982). Time, 120(23), 49.

UN Convention Against Transnational Crime (2000).