The Washington Post

By David Brown

I’d had enough of destination travel. For the next couple of days, I thought to myself, I could stay right where I was — the town of Bhalil (pop. 12,000) in the Middle Atlas region of Morocco.

I had been visiting a friend who had an art residency in the northern city of Tetouan, but he was in a fit of creativity and had no time for sightseeing. I had rented a car, headed south, and visited Meknes, Volubilis and Fez for a week. Now, I was heading back, looking only for a place without much traffic. Lonely Planet called Bhalil a “curious village . . . worth a visit if you have your own transport.”

I was in the old part of town, in a stucco guesthouse called Dar Kamal Chaoui Maison d’Hotes. The only other guests were a couple from Germany with two children, who had eaten earlier. Now it was dinner time for the staff — my Moroccan host, Kamal, and his cook, Naima — and me.

As we finished the soup and prepared for the next course — chicken tagine with pears — a knock came on the door. Naima answered it. After a minute she returned and whispered to Kamal, her lavender scarf framing her pale face.

“There are three girls at the door — students — who want to ask me about the history of Bhalil,” Kamal said, turning to me. “Do you mind if they come in?”

Of course not. Now I wouldn’t have to ask all the questions.

Three girls — 13 and 14 years old — entered the room and sat at the far end of the table. They were a picture of Moroccan demography — one Arab, one African, one European. The girl named Selma had a notebook and pen and sat in the middle.

He tested their French with more questions, and when he judged it inadequate for the urgency of the task, launched into a lecture in Arabic about three things that make Bhalil unusual.

No. 1: Caves formed by the Atlantic Ocean, which the original inhabitants incorporated into their houses.

No. 2: Buttons for djellabas, the traditional caftans worn in the region. A single garment can have more than 100 of the buttons made from knotted thread. Bhalil is where they’re made.

When he finished his talk, he called the girls to the head of the table. (“I shouldn’t be doing this. They won’t learn,” he said ruefully.) He asked them to repeat, in French, what they had heard. He corrected their grammar and took dictation in Selma’s notebook. (“My English is not good, but I am mad for French,” he said in a stage whisper.) When they were finished he pointed to his eye and said: “Watch me” and read the whole thing in a radio voice. He had each girl read one of the parts. Then we all had dessert to a chorus of “merci beaucoups.”

After the girls left I told Kamal he was a great teacher, but that was an understatement. “Kamal and the Night Visitors” was a virtuoso performance of pedagogy, emotional intelligence and civic pride.

Trails and trash

Bhalil consists of several inhabited hillsides, the guesthouse on one of them. Looking south from Kamal’s third-floor deck you can see a ridge with houses partway up, then rocks and cliffs, and at the top a flat band of ocher earth. For a fee, Kamal will take you on a walk in that direction — four hours for $58, or eight hours for $92. (For $23 more you can get a barbecue at a farm.)

The next morning, I still wasn’t feeling great and opted for the short walk. We headed off at midmorning, Kamal carrying nothing but two cellphones. He was dressed in black, with his glasses tipped up onto his head of black hair, giving him a movie-star look.

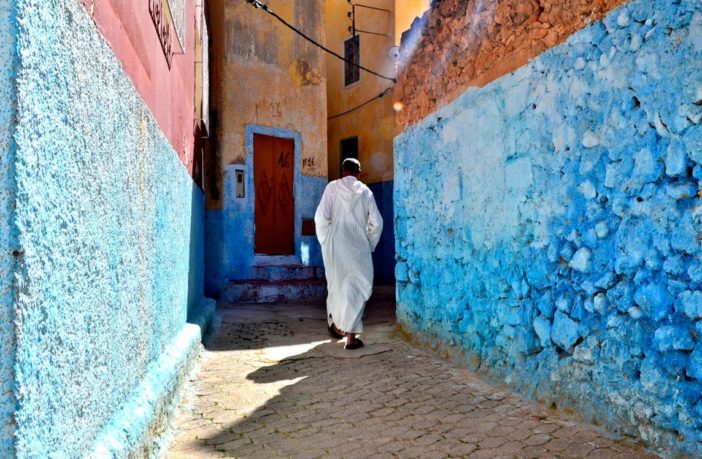

Kamal’s neighborhood still had some houses with rooms carved out of limestone caves. (“Troglodytic dwellings,” they’re called.) The paths aren’t wide enough for motor vehicles other than miniature excavators and front-end loaders, several of which were repairing a water line. The lanes nearby were noticeably free of litter, and many of the houses freshly painted. This was no accident. Kamal is a one-man improvement association, urging neighbors to paint their houses and sometimes doing it for them. He picks up trash and shames those who don’t.

“This is what the children eat today,” he said when we were out of earshot. “An uncle comes to visit and gives a dirham to each child. They immediately come here and buy this. But it is not good food, these biscuits. And then the package ends here.”

Across from a donkey stable, a pile of trash had rafted up against a prickly pear cactus, which got Kamal started again. “The people do not see this,” he said, jabbing his index finger at the corner of his eye. “They see when something is broken, but they do not see this.”

The road soon became a narrow trail winding between pockmarked limestone boulders. There were no distractions and I could ask questions as we climbed.

Today, he’s a man on many missions, not just an anti-litter campaign. He believes in neighborhood solidarity. He thinks Bhalil is undersold as a tourist attraction. He promotes three things — environmental consciousness, tolerance, and civic engagement. “I believe I have a duty to improve my country,” he says without embarrassment.

His wife eventually grew tired of living in Morocco and returned to France. She lives near Nice with their youngest child and helps manage a hotel. (The other two children are studying in France and working in Germany). He and his wife get together every few months. She had been in Bhalil 10 days earlier. Kamal spoke of this as a permanent arrangement necessitated by his mission, and I didn’t probe further.

We passed a sheepfold with dry stone walls, a roof of scavenged tree trunks and plastic, and two padlocked doors. In the distance, Kamal saw two men and shouted a greeting. “I have seen these men before,” he said. “They wonder what I am doing.”

The top of the ridge was a windy plain. Kamal opened his arms like a child. Throwing-size rocks covered the ground so uniformly it would be impossible to run across it without turning an ankle. Kamal crossed the plateau and I stopped to take notes. When I got to the other side and descended to a dirt road below the brow of the hill, I saw Kamal talking to a boy of about 15. He wore a blue polo shirt buttoned to the top.

Four years earlier, a Canadian couple stayed at the guesthouse. They had flown to Lisbon, ridden south on bicycles, crossed the Strait of Gibraltar to Morocco, and then ridden to Bhalil. They offered the bicycles to Kamal as partial payment for their room on the condition he would find someone who needed them.

At the time Mohammed was going to an elementary school close to the settlement where he lives. Kamal gave him one of the bikes. The boy now attends high school in Bhalil. He said he still has the bike, but doesn’t take it to school because the climb out of town is too steep for riding. Kamal held the boy by the sides of his head, and then clapped his hands in front of his face, as if to set him on his way.

As we crossed a field at the bottom of the hill and headed back to Bhalil, we saw a girl herding sheep. Kamal had earlier said that Mohammed’s sisters didn’t go to school, and I asked if this might be one of them. He said it was possible. He regretted that some girls in the countryside didn’t go to school, but said that many were satisfied to work on the farm until they got married.

Morocco has a shortage of teachers; the schools in Bhalil are on double sessions. I asked why the progressive king — whom everyone seemed to like — didn’t make education for girls a priority. He said the king couldn’t do everything. It was an unKamal-like view, but I didn’t challenge him.

(Later I searched the Web and found a source that said that 79 percent of rural boys in Morocco attend school, but only 26 percent of girls. Another had a graph showing that 19 percent of rural children of primary school age are not in school, compared with 4 percent of urban children.)

When we got to the edge of town, Kamal started picking up trash again. I couldn’t tell if this was a compulsion or for show. He quickly had his hands full and deposited the collection in a neighborhood trash bin. Almost home, he engaged a man in conversation and handed him an empty yogurt container. He had been telling the man — a hairdresser — for months to put a trash can outside his shop. The man hadn’t, he said, because he wouldn’t know where to empty it.

“I told him: ‘Stop thinking — it will give you a headache in your small brain,’ ” Kamal said as we walked away. Then he added: “I am very bad. I have to repress my anger.”

Shades of a village

I was feeling better the next morning, but there was no time for further exploration. The drive back to Tetouan would take at least 4½ hours. I brought my bags down to the front hall. Kamal was in the office on the computer and said he wanted to show me a few things before I left.

We headed down his lane to the paved street. “This is the house of one of the richest men in the neighborhood,” he said, pointing to a house that was lavender the first four feet above the paving stones and above that cream. “He kept saying, ‘Oh, no, I don’t have the money to paint it.’ So I just did it for him.” Nearby were houses with yellow walls and pink highlights, green doors and magenta utility boxes — a street of walk-through Rothkos, the painter on antidepressants.

We stopped at the workshop of Latef Abdellaoui, a carpenter and artist who Kamal has on a retainer. He had made a series of paintings of local people that Kamal had set into the exterior walls of the guesthouse. His workshop, in one of Bhalil’s repurposed caves, was as full of alluring objects as a cartoon treasure trove. Kamal climbed onto its roof with a ladder and opened two shutters under a tiny awning. Inside was a mixed-media painting of storks nesting on a minaret, made by an artist who had sojourned in Bhalil for a month. It was art for the neighborhood, open for business.

Naima appeared on her way to buy milk, wrapped in a mauve scarf that matched a section of the wall where she waved to us.

Where the lane hit the paved road was a red house. Along one of its walls were boxes of plants — geraniums and chrysanthemums, basil and hot peppers. Soon after he opened the guesthouse, Kamal had put out planters in the neighborhood. He was told that people would steal them, and he had said, “That’s fine, let them.” However, he hadn’t expected a request for plants from the woman in the red house.

Four years earlier he had approached her with a deal: He would pay to paint her house if she agreed to have a sign for his establishment, and an arrow directing people to it, on the wall facing the paved road. She said yes. He paid 400 euros for the paint job and 100 euros for the sign.

Soon, however, he started to hear about how he was ruining the neighborhood. “Every evening, she sees the guests coming with luggage. They know I am making money. It is just jealousy.” Three months later, Kamal went out of town for several weeks. When he returned, the house had been repainted and the sign was gone.

He didn’t put up a stink; in neighborhood improvement he’s playing the long game. However, he was surprised when a year later the woman asked for 10 plants, and then 10 more, which he delivered. The request wasn’t the only irksome thing. “This is from southern Morocco,” he said pointing to the red wall. “The color of the earth. In northern Morocco, the color should be white or yellow.”

As he was telling the story, a young woman in a headscarf walked down the hill on the paved road. Kamal recognized her. She was 17 or 18 and going to a university in Fez four days a week, studying chemistry.

“Why do you cover your beautiful hair?” he asked. “My mother wants me to,” she said glumly. She said she was going to be married next year and would move to Fez, but would continue her studies. “Why are you so sad?” Kamal asked. She answered. He turned to me: “Her father has passed away recently.” We nodded in sympathy and she continued down the road.

A woman in a green do-rag walked in and out of the neighborhood twice while we were talking. Kamal shot her a glance. “This one will tell everyone what we have been doing,” he said. “And first tell this girl’s mother that she has been talking to two men.” I asked him if he thought the young woman would finish her college studies. “It is unlikely,” he said.

We could have stood there for hours talking to passersby and sampling the neighborhood. But it was time to go. We walked back to the guesthouse and Kamal totaled the bill. It was 2,684 dirhams for two nights, two dinners, a mountain trek, parking, bottled water, and city tax — about $280. This was expensive by Moroccan standards and a bargain in every other way.

During one of his anti-litter diatribes, I had asked Kamal whether he had thought of putting out trash baskets and paying someone to empty them. He could think of it as an experiment in consciousness-raising, and ask his guests to chip in spare dirhams to help pay the labor costs. He liked the idea.

After we settled up, I gave him another 500 dirhams. “For the trash baskets,” I said. He came around the desk and gave me a hug.

Now I have a reason to go back to Bhalil. But it’s only one of many.

Brown is a freelance writer based in Baltimore. His website is aweewalk.com.