Business Insider

Harrison Jacobs

all photos by: Annie Zheng

It beats every other mode of transportation in Morocco. Annie Zheng / Business Insider

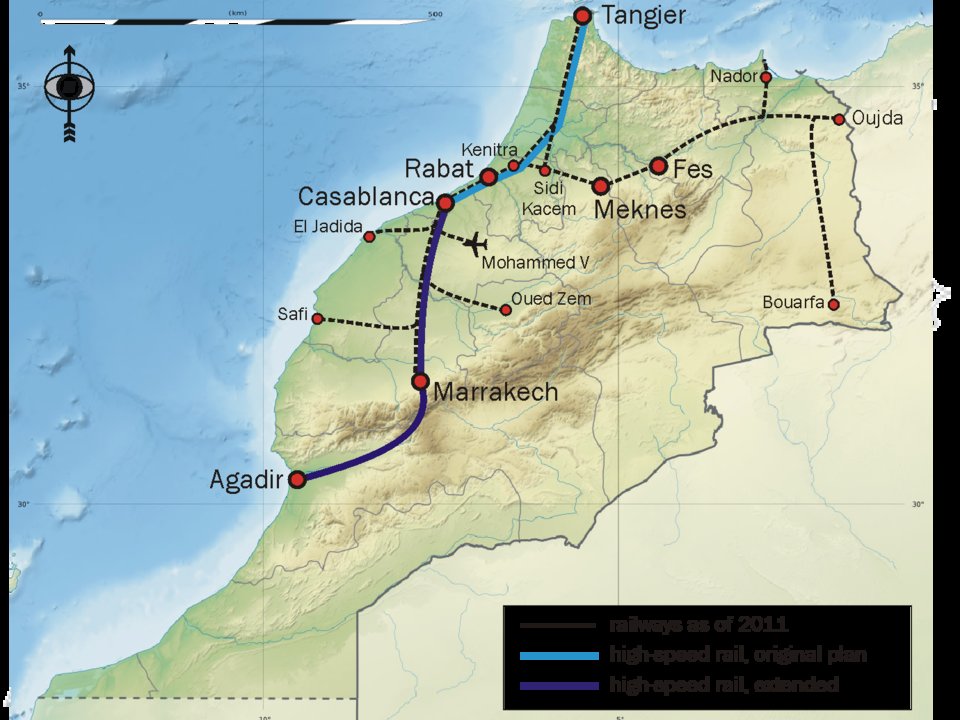

Morocco recently unveiled the first high-speed railway system in Africa, connecting the coastal city of Tangier with the capital, Rabat, and Casablanca, the country’s business hub — and eventually the tourist destinations of Marrakech and Agadir.

Last month, I rode the train roughly the distance between New York and Washington, DC, in two hours. The ride, which takes over five hours on conventional rail, is set to be cut down to 90 minutes.

I found the experience delightful, with cheap first-class tickets, plush comfortable seats, air-conditioned cabins, plenty of leg room, and an interior design that evoked rail’s golden age.

While the $2 billion train system is impressive, it’s hard not to think of the robust public debate happening in Morocco that has left some critics questioning the economic viability of the train.

People often visit Morocco for a glimpse of the past.

There are snake charmers and monkey tamers putting on a show for tourists in the central square of Marrakech, and winding labyrinths of the country’s old medinas. There are remote mountain villages that make you feel like the first foreigner to have ever stepped inside, and golden, timeless seas of sand.

One thing most people don’t visit Morocco for, however, is a glimpse of the future. The Moroccan government and its king, Mohammed VI, are hoping that will soon change with the opening of a high-speed rail system.

Opened in November after over a decade in development, the Al Boraq is Africa’s first high-speed train. Morocco is hoping that foreign investors and Moroccans will look to the project as evidence that the country is on the fast track to progress. Whether that is actually the case is up for debate.

“In French, it’s called ‘les grands chantiers,’ the closest translation of which is ‘grand design,'” Zouhair Ait Benhamou, a doctoral candidate at Paris Nanterre University who studies big-ticket projects like Morocco’s high-speed rail, told The Guardian last month.

For some Moroccans, the train is an expensive folly whose funds would have been better spent on overcrowded schools or the overtaxed medical system. For others, the belief is that the benefits of having futuristic infrastructure will “trickle down” to the rest of Morocco. Only time will tell.

After riding similar trains in China, Russia, and Korea, I knew I had to give Morocco’s version a try. Here’s what it was like to ride first-class from Tangier to Casablanca.

I arrived at the Tanger Ville Railway Station in the northern coastal city of Tangier about a half hour before my train at 5 p.m.

Though the station opened in 2003 with regular rail, Morocco spent $37 million to renovate it and add a building for a new high-speed train system.

Source: Morocco World News

While Morocco already has an extensive rail network that serves 40 million passengers, the country has been developing high-speed rail for a decade.

The $2.3 billion project has been funded with nearly $1 billion from France and $500 million from Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and the United Arab Emirates.

The first leg of the project — from Tangier to Casablanca, Morocco’s business hub — opened in November.

Plans are underway to extend the line to the tourist hotspots Marrakech and Agadir in the next few years, and eventually Fez.

Many analysts have suggested that the bullet train is about more than the revenue it will generate — it’s “a flagship project that enables Morocco to shine in Africa,” one geopolitical analyst told The Guardian.

The spotless, light-filled Tanger Ville station sends the message that the train is as much about prestige as anything else.

Source: The Guardian

As I’ve observed with the high-speed rail stations in China, the Tanger Ville station looks more akin to an airport than a train station. There are high-end shops, a cafeteria, and even a first-class lounge.

It’s important to remember that the bullet train is far from the only big-ticket infrastructure project the Moroccan government has invested in. Over the past decade, the country has developed numerous ports and a $600 million solar plant considered the biggest in the world.

Source: CNN (1, 2)

It’s important to remember that the bullet train is far from the only big-ticket infrastructure project the Moroccan government has invested in. Over the past decade, the country has developed numerous ports and a $600 million solar plant considered the biggest in the world.

Source: CNN (1, 2)

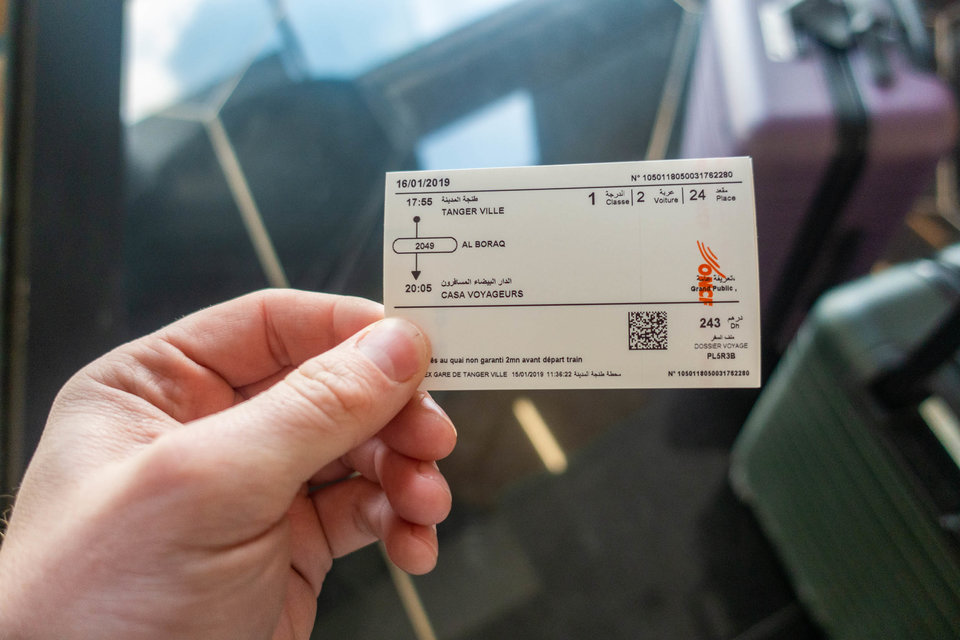

Buying a ticket is very easy. You can buy online from ONCF, the Moroccan train authority, or in the station.

Fares for the high-speed train are about 30% higher than those for a regular train, which costs $14 to $27.

Source: ONCF, Travel + Leisure

A helpful sign tells you all the train times for both regular and high-speed trains.

All trains leaving Tangier pass through Tanger Ville station, so you don’t want to buy tickets for the wrong one. A ride from Tangier to Casablanca on the regular train is a whopping five or six hours.

The machines are easy enough to use. Anyone who has visited a major city and used the metro system can figure it out. It accepts cash and credit cards.

Depending on the time, high-speed fares range from $15 to $24 for a second-class ticket and $25 to $38 for a first-class ticket.

Source: Morocco World News

I got a first-class ticket for $25.

Stop TGV, a local coalition that has protested the project, has said the fares are a third of what they would need to be for Morocco to pay back its loans to its international partners.

But Mohamed Rabie Khlie, the director general of ONCF, has said that it’s important that the train be able to serve all Moroccans and not just “a high-end clientele,” and that keeping costs down is a major part of that.

Source: The Guardian,Stop TGV, Le Monde

After getting my ticket, I headed to the Al Boraq lounge for people traveling on the high-speed train.

Mohammed VI named the high-speed train Al Boraq after a mythical winged horse in Islamic culture.

Source: Maroc

The lounge was nice but packed. The downstairs was filled with people, and no seats were available.

Analysts have expressed worry that the high-speed train will not be able to get enough passengers to become profitable. Khlie has said the rail would need to double its volume to 6 million passengers annually within three years of operation.

Source: Le Monde

At least there was plenty of free coffee, tea, and hot chocolate.

I made myself a hot chocolate and looked for a place to sit for a few minutes.

Thankfully, there was an upstairs.

Benhamou told CNN that in the event the high-speed rail doesn’t reach 6 million passengers annually within three years, the government would have to give out subsidies.

Source: CNN

The vibe of the Al Boraq lounge was very tech-coworking-space circa 2016.

The government hopes that the high-speed train will encourage foreign investment in the country and convince global business leaders that Morocco is an attractive place for development.

The Al Boraq lounge was one of the few places that I found working public WiFi over about a month in the country.

The Tanger Ville station can feel worlds away from the parts of Morocco like the undeveloped rural interior of the country.

It’s understandable why the railway has infuriated people like those in charge of the Stop TGV campaign and politicians like Omar El Hyani, a Rabat city councilor, and Omar Balafraj, a member of parliament for the Federation of the Democratic Left political party.

To critics like Balafraj and Hyani, the railway is an expensive project that is big and loud but does little to help everyday Moroccans.

“Morocco is a poor country, and the top priority should be education,” Balafraj told CNN.

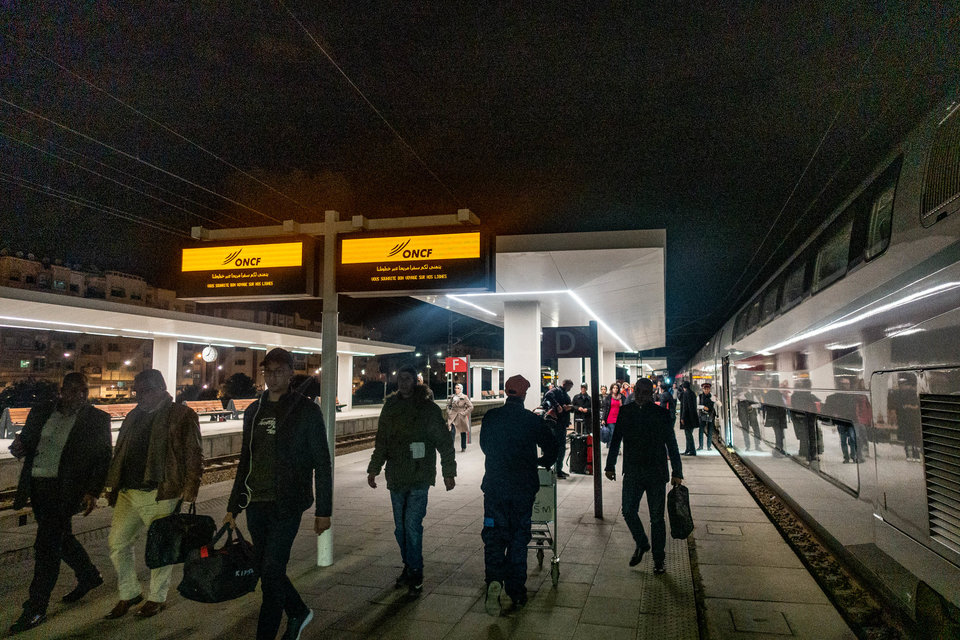

As a voice over the intercom informed me and the other passengers that the train was ready to board, I headed out to the platform.

The project does have the support of many Moroccans, a point that even critics concede. Hyani told The Guardian that “in Morocco, when you present people with a fancy new idea, they tend to agree with it,” though he added that the phenomenon was due in part to skillful propaganda.

There’s a sign that lets you know whether you are at the correct platform.

It’s easy to be dismissive about the prestige factor, but I saw the excitement of Moroccan passengers, many of whom took selfies in front of the train.

As Hassan, an IT worker in Tangier, told Morocco World News shortly after the opening: “Those who say that it is all about prestige are right. But they are missing something important: Prestige counts for an emerging country that aspires to greatness, to big development plans.”

Source: Morocco World News

Because I’m a bit of a worrywart, I double-checked the other sign above the train to make sure I was getting on the right one.

I didn’t want to end up in Fez.

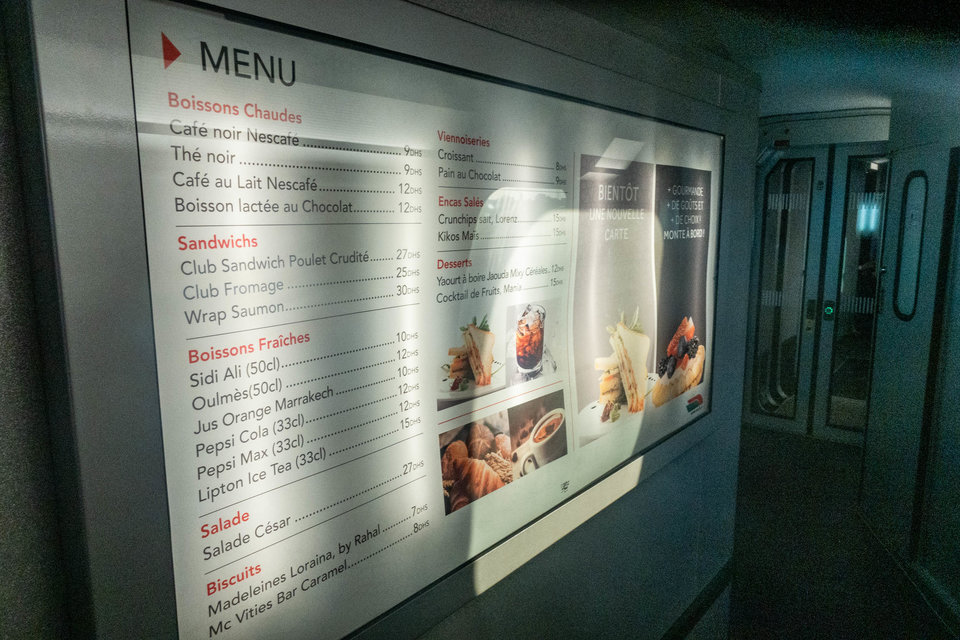

As I walked, I made a mental note of the cafeteria car.

Unlike the trains of old, most high-speed trains don’t have a traditional dining car but a cafeteria car that sells a few snacks like sodas and sandwiches. The one exception was the bullet train in Russia, which had full meals.

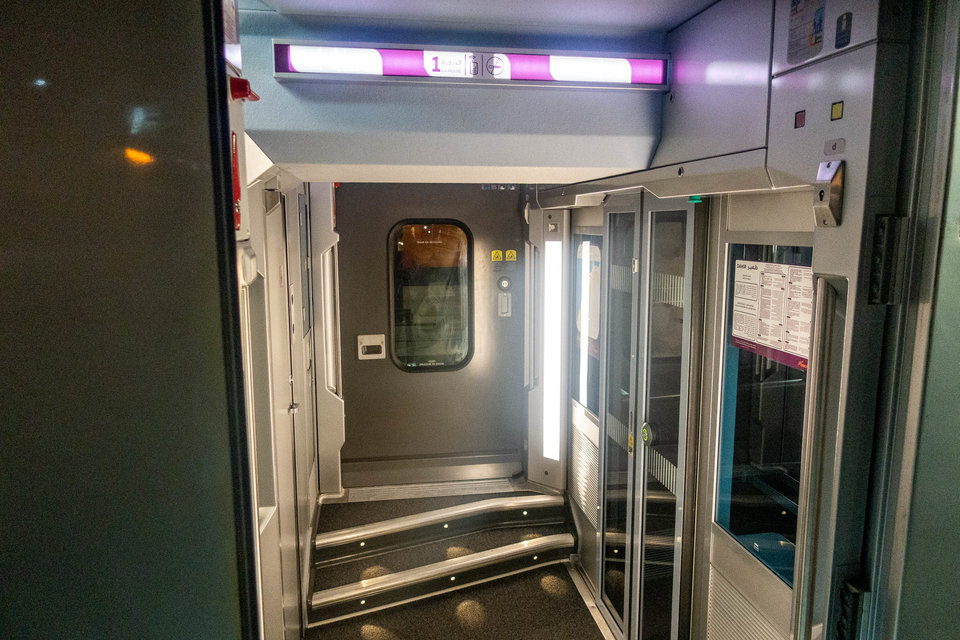

The first-class car was at the end of the train. I almost went into the wrong car a few times.

Morocco’s high-speed trains are double-decker cars made by Alstom, a French manufacturer of high-speed rail systems for countries all around the world. Still, the feeling among some Moroccans is that the French company got a “sweetheart deal” because of France’s colonial history with Morocco.

Source: The Guardian

As I walked into the first-class cabin, I was struck by the distinctly Moroccan interior.

The seats are covered in a rich red fabric.

There’s a large set of racks to stow your luggage.

Much better than keeping it underfoot or on my lap.

I enjoyed that the design had an old-school flair that integrated classic elements like the art deco lamps and seats that face each other.

It was classic and modern at the same time.

Not all the rows were double rows that faced each other. But I happened to be in one.

The benefit was that I had extra leg room. The downside was that I had to negotiate with the person across from me for the space.

Each seat reclined via a motorized switch. It was a little jarring at first.

Pressing the button opens the seat part so you can extend your legs, while also reclining the back section.

Each row had a privacy shade to block the sun.

It was very needed during my sunset train ride, with direct sunlight in the compartment as we rode down Morocco’s Atlantic coast.

There were a couple of hooks on each row so you could hang your jacket.

For anyone thinking Morocco is warm year-round, fair warning: The winter is bone-chilling cold.

Each row had a power outlet so I could plug in my laptop. But there seemed to be only one power outlet per row.

So if you get unlucky, you’ll have to make friends with your neighbor.

The tray table on the double rows folds out for each person. It’s a much roomier table than you’d typically get on an airplane.

There’s plenty of room to spread out and work.

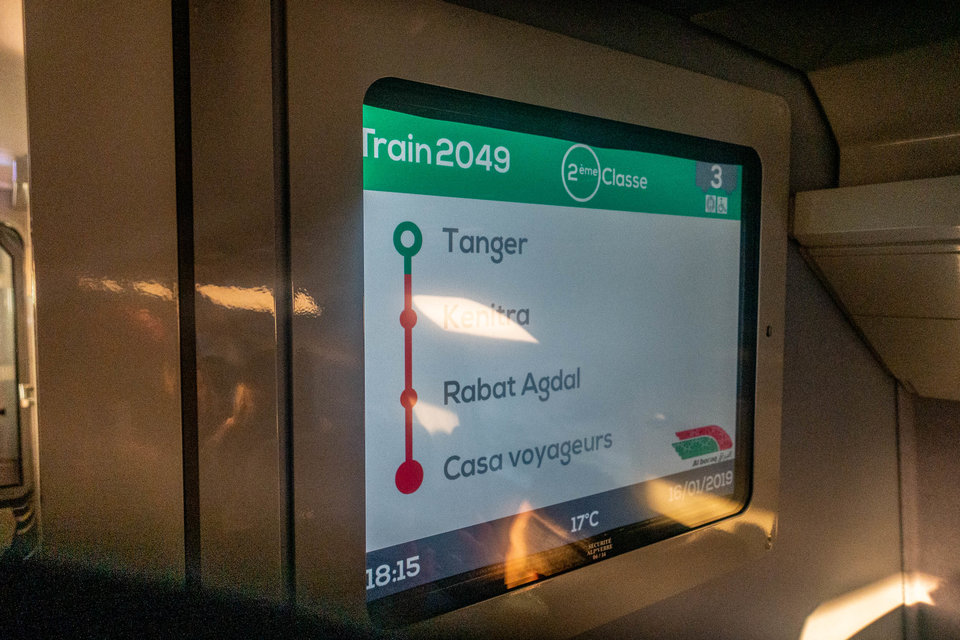

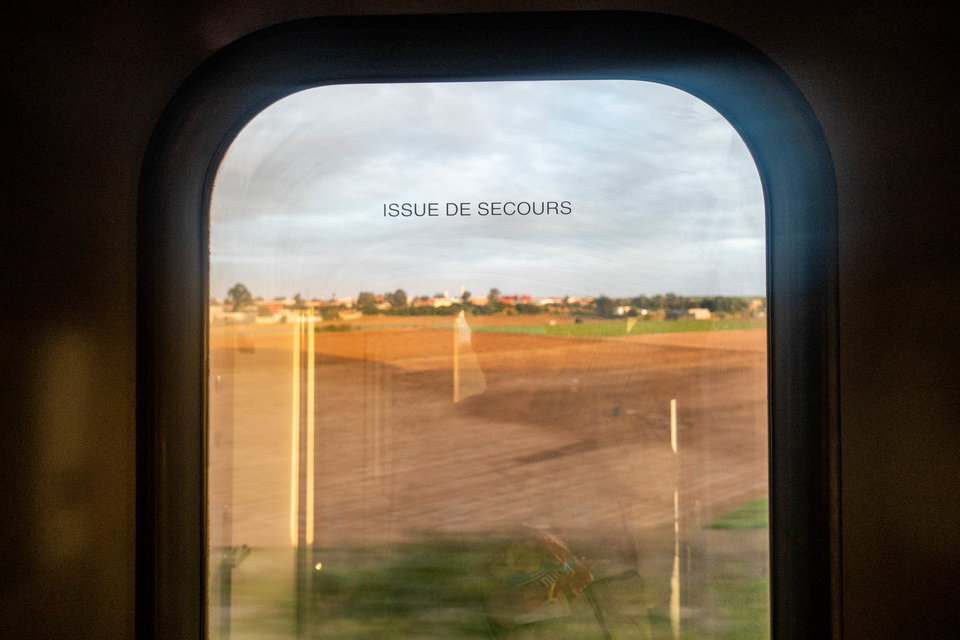

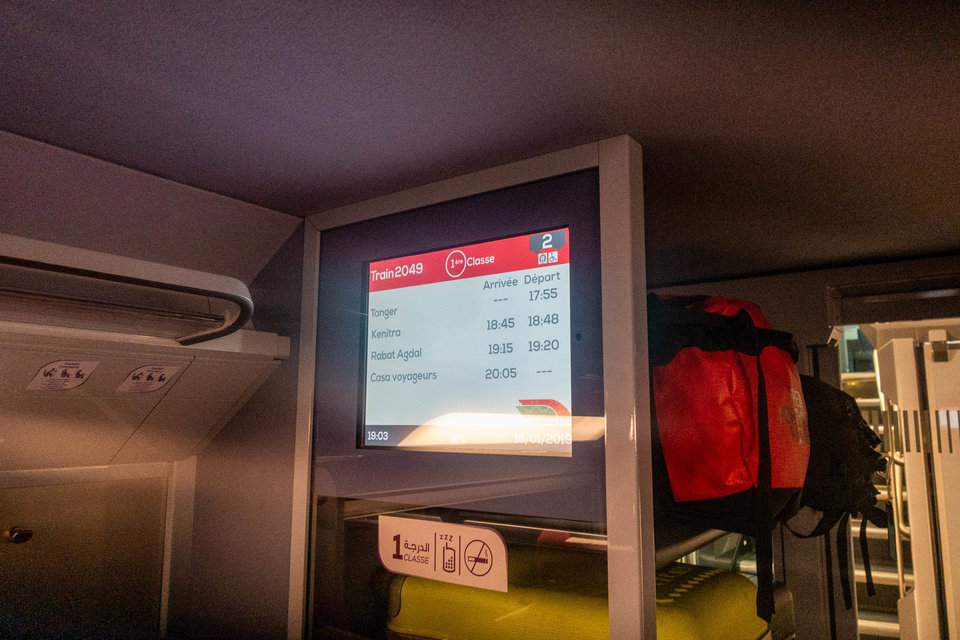

With no stops until Kenitra, 128 miles south of Tangier and almost all the way to Rabat, the train quickly picked up speed.

The landscape blowing by is sea and beaches on one side and rolling green hills and pine forests on the other.

The high-speed train to Casablanca takes about two hours and 10 minutes, less than half the time it takes on a regular train.

After about a year or so of track improvements, that time is set to be cut to a blazing 90 minutes.

Source: Telegraph

After settling in, I walked through the train to get a feel for what the other compartments looked like.

To be honest, the second-class compartment didn’t look much different from first class. The seats were leather (or fake leather) and not as plush, but otherwise I couldn’t see a difference.

The second-class compartments were closer to the cafeteria car as well.

I had to pass through three or four cars to get to it.

The menu was nothing to write home about: a mix of sandwiches, coffees, pastries, and snacks.

But with the longest ride on the train topping out at a little over two hours, it makes sense that it wouldn’t be more elaborate. I’m sure most people will wait to eat a real meal.

I bought a bag of chips and took a moment to take in the landscape.

It was passing by almost too quickly for my camera.

By then, the train had hit its top speed of 320 kilometers per hour (200 mph).

That’s a lot faster than Amtrak’s Acela Express, the fastest train in the US, with a speed of up to 241 km/h (150 mph).

The cafeteria car had a retro but futuristic vibe with its curved ceilings, wavy bar table, and colorful stools.

It reminded me of what people in the 1960s imagined the future would be like.

After finishing my bag of chips, I headed back to my car for the remaining hour or so of the ride.

Each car is separated by these automatic doors. You press a button to open them.

You could feel the higher speed, though it’s probably a credit to the engineering that I didn’t feel it too much.

I only really noticed the speed when I looked out the window and saw the scenery whizzing by.

The scenery in Morocco never stops being stunning. To be honest, it wouldn’t be so bad to take the slow train.

The bathroom, though new, didn’t seem well kept. The bathroom for the first-class cabin had rust already forming around the sink and soap spilling out of the dispenser.

The other bathrooms must’ve looked worse.

The two-hour ride goes by quickly. Before I knew it, we had passed Rabat and were just a few minutes away from Casablanca, the end of our journey.

Having done many daylong car trips all over Morocco over the previous month, I can’t wait until the service is extended to major tourist hubs like Agadir and Marrakech.

Though the train’s Moroccan critics have a point about public resources being put into a shiny bauble, it’s hard to ignore how well such developments have worked out for similar developing countries.

China famously has facilitated much of the development of its ultrafast rail network. Russia — and soon India — is aiming to do the same thing.

Morocco’s success will largely depend on whether foreign investors buy what it’s selling and, more crucially, whether Moroccans use the train as much as the ONCF is projecting they will.

The train came into the Casa Voyageurs station, the primary train station in Casablanca.

While it has been open since 1923, the station was recently renovated for $47 million in preparation for the high-speed train.

The Casa Voyageurs station looked just as snazzy as the Tanger Ville Station.

While it will take some time for Morocco and the global cabal of analysts to determine whether the high-speed rail project is a success economically, from a tourist’s perspective the experience couldn’t have been better.

As I always do after riding a bullet train — whether in Korea, China, Russia, or Morocco — I wondered why the US can’t execute such large projects. But one thing I’ve learned is that these projects usually happen in countries where ruling parties can make decisions without public debate.

That’s what happened in Morocco too. Balafrej described the train to The New York Times in 2012 as “a symbol of a Morocco that we do not want — where the most important decisions … are made without consultation or a public and democratic debate.”