The Canyon Country ZEPHIR

April 1, 2012

By stiles

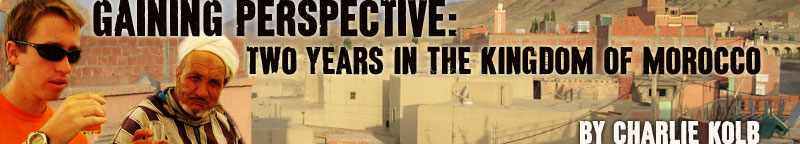

Winter is slowly leaving the High Atlas as I pass the milestone of having been a Peace Corps Volunteer serving in Morocco for two years now. Two years; it’s hard to believe that it has been so long since I left my old life behind in the states to come here. Sometimes I think of who I used to be, but I have a hard time remembering. I know that I went to college and studied to become a biologist there, I know that I worked all over the country as a Ranger for the National Park Service, I remember the faces of family and friends back home, but they don’t quite seem real. It is as if I am reliving someone else’s memories. The only things that seem unchanged in my psyche are the images that I hold of the Southwest. Those memories seem as fresh and as vital as the day they were made.

When I close my eyes at night, I see the snowy La Sals shining above the redrock of the Spanish Valley and I see nameless hanging valleys in the San Juans painted from side to side in broad strokes of lupine, fireweed, and columbine. Sometimes the towering monolith of Druid arch shimmers into view, at other times it is something as simple as a winding mountain stream lined with willows and teeming with trout. I smell juniper smoke on the breeze, hear coyotes yowling their woes to the desert stars on endless moonlit mesas, and feel the cool touch of rain-heavy wind on my face as I stand in a labyrinth of redrock spires. These memories remain constant; unchanging in my mind’s eye as the very definition of what it means to be home. My time here is short, less than two months remain before I can go back, and feel that I have finally earned a place in paradise.

Just recently I visited a good friend in another part of Morocco. He and I trained together back in the village in the Dades Valley, on the edge of the Sahara. Though training seems like an eternity ago, this is the first time for me to see where he lives and works. His site is similar to mine in many ways, however the valley where his village sits is much more wide and deep. The mountains tower overhead, crowned with winter snow. Looking up, I am forcefully reminded of Colorado and the San Juans I left behind, what seems so long ago.

One night, after accompanying another volunteer back to her home, while my friend was occupied with other things, I found myself walking back to his mud house from a neighboring village. I was completely alone in this moon-draped valley. The road rolled away before me into the grey distance, a silver ribbon beneath a sea of cold stars. The snowcapped mountains shone in the moonlight, their heights icy and pale with distance. On a conical hill high above the valley floor, an ancient Berber fortress was perched, a signal beacon from ages past wreathed in millennia of legend and half-forgotten stories. It is times like this that I am able to recall the original feelings of awe and wonder I experienced when I first came here. I have been truly lucky to have lived and worked in a place so steeped in beauty and mystery. The Atlas Mountains convey a sense of immense age and experience; venerable and stately, they make our younger Rockies seem but callow youths by comparison. I enjoy the stillness awhile longer before I arrive back at my friend’s house and retire for the night.

My friend’s valley and mine are both considered strongholds of Berber culture; the way of life here has changed very little over the past thousand years. Shepherds still tend their flocks among the cloud-shadows on the mountainsides, and women still cut grass by hand, carrying it home in a cloth on their backs when the sun sinks behind the western hills in late afternoon. Robed and hooded men still ride their laden donkeys to market every week, and the mosque sings out the call to prayer five times a day, punctuating the slow, gentle rhythm that seems to define life here. Both our villages are ruled by tradition, all ancient and some difficult to comprehend from a western perspective. But it cannot stay this way forever.

My village has changed almost to an incredible degree in the past few years; even since I arrived it has become a different place. It is as if western culture has taken root here and is growing at an exponential rate. This really started with French occupation of Morocco throughout the first half of the 20thcentury. Their ruined fortresses still stand watch over the valley where I live, a testament to a war fought and lost over a series of decades. Although the governance of Morocco has long since been returned to its king and its people, the seeds of westernization planted during the occupation have continued to grow and spread. My village, even five years ago, was without water or electricity. Phones were unheard of until recently and, though there has never been a landline in the valley (at least to my knowledge), there are now cell phone towers on most of the ridges and nearly every person owns a mobile phone. One of the first things I learned to do here was to send text messages in Tamazight.

As I have mentioned before, the fact that the traditional lifestyle has done untold ecological damage to the Atlas makes western culture seem increasingly more attractive as conditions grow harsher with each passing year. In my area, there is very little left of the original food web save for a very small number of species that continue to hang on for dear life.. These alternatives are presented daily to nearly every Moroccan on television, if a family has electricity you can bet they have at least one TV. While some parts of westernization could certainly be positive (green energy and conservation come immediately to mind), they are rarely presented to the average Moroccan.

When I look out over the ‘Old City’ of Fes, every rooftop is crowned with at least one satellite dish. They all face the same direction and add a strange element of uniformity to the otherwise jumbled chaos of the labyrinthine Medina. A friend of mine once described them to me as “the flower that blooms in Peacetime”. Television, though mostly local stations, still paints a picture of rich, western lifestyles as the ideal. Spanish and Turkish soap operas, poorly dubbed into Moroccan Arabic, or Hollywood movies with Standard Arabic subtitles make up a majority of the programming. Most of the people I see on TV are manipulative, promiscuous, and wealthy even by our (beyond comprehension) “American” standards. There is no frame of reference to separate truth from fiction; nothing to indicate that very few people in the western world live or act anything like the caricatures portrayed on TV every day. Most of the foreigners that Moroccans, especially those in my village, ever get a chance to meet are tourists; who do little to dispel these ideas being hammered into my friends’ heads by modern media.

Most tourists come in driving nice 4×4 SUVs, outfitted like they are going on Safari, which amuses me; Morocco may be exotic, but it is nothing compared to Sub-Saharan Africa (referred to by most Peace Corps Volunteers here as “real Africa”). Oftentimes, these visitors will not even leave the land-rover, sometimes giving me the impression that they are afraid of the people here. When they do exit the vehicle, they give away pens, candy, and occasionally even money. This behavior seems to confirm Moroccans’ suspicions that allforeigners are incredibly wealthy, and therefore must live like the characters they see on TV. There are tourists that are exceptions to this rule. Indeed tourism may be one of the driving forces that will keep this culture alive in the modern age (I’ll get to that later), but the fact that nearly every child older than four years knows the French words for “candy”, “pen”, and “money”, is very telling.

To me, this is why Peace Corps is so important. There are almost 250 of us currently serving in Morocco, and we have been doing so for fifty years. While Peace Corps has three goals, only the first relates to so-called “development” work. The second goal is to “facilitate an understanding of American Culture with the residents of the Host Country”. I translate this to mean that I am tasked with correcting misconceptions about my home culture, both positive and negative. A quick aside: the third goal of Peace Corps is to “facilitate an understanding of Moroccan culture with Americans”; the fact that you are reading this now means that I am, in fact, doing my job. I have corrected many misconceptions about American Culture in the past two years, to the extent that some of my friends have confessed to me that they were completely wrong about what they thought of America before I got here. They know that not all foreigners are wealthy (hell, I’m poor as dirt), obese, shallow, debauched, etc. However 250 Americans at a time are not going to dispel preconceived notions quickly and we certainly can’t reach everybody, so the prevailing view continues to be “as seen on TV”.

The TV is on almost the entire day in the houses of most of my local friends; it provides a background for whatever they happen to be doing. It is also a status symbol; everybody who is anybody owns a TV. Naturally the fact that I, not only do not have a TV in my house here, but that I also grew up without a TV (my parents threw it out when I was five), is unfathomable to many people that I meet. The fact that I readwhen I sit in a café during the day (or write, like I am doing now) is also viewed as intensely strange.

The influence of these western ideas spread through mass media, of which another particularly misleading source is “rap music” (still my favorite oxymoron), is evident in the younger generation, especially the teenage boys. Skinny jeans and leather jackets abound and those I don’t know usually talk to me by shouting rap lyrics at me.

Weekly market is filled with western goods and clothing, most of it knock-offs of popular brands such as Nike and Adidas; it is not unusual to see men sporting “New York baseball” caps, or even some that say “Budweiser” or “Heineken”. Since drinking alcohol is considered shameful in this culture (though this is not to say it does not occur on a very frequent basis) many people would be humiliated if I told them what their hat or t-shirt actually said. Granted there are worse examples of this; a stately berber woman carrying a totebag with the playboy logo on it comes immediately to mind. It makes me angry to see what some would consider the worst pieces of our culture openly displayed (albeit not usually understood) in a place as culturally unique as the eastern High Atlas. Where do these goods come from? No one seems to be able to tell me and, since the answer seems likely to be America, I am not entirely sure I want to find out.

Most Moroccan youth that I talk to seem to be resentful of their roots; their culture and tradition, which they say is antiquated though I say it is unique. In their minds it is holding them back and preventing them from achieving the wealth and power they perceive as being the norm in western society. They seem to be the voices of discontent here, not the older generations, many of whom are some of the mostcontented people I have ever had the pleasure to meet. With the young now in the majority, the “Arab Spring” was not terribly surprising to me, though how quickly it spread certainly was. Looking at the young people on one hand, and how unhappy they seem to be, and seeing so many older Moroccans still happy to live just as they have since time immemorial, it makes me wonder just how positive this change will really be.

While I am certainly a big fan of democracy (when applied correctly), I am rather wary of the homogenization and westernization that seems to follow behind it. While improved human rights (especially women’s rights) are without question a positive change, viewing the original culture from which the nation sprang as “obsolete” or “barbaric” (which the word that “Berber” unfortunately comes from, which is why I prefer “Imazighn”, which is what they call themselves. Much like “Navajo” vs. “Diné”, this is an entire other can of worms. For the purpose of this piece, I will continue to use the term that is best known), I believe is a mistake. Our cultures make us who we are; if we forget where we came from, then how in the hell are we supposed to know where we’re going? When I look into the eyes of young Moroccans and they talk to me about how ashamed they are of their “primitive” culture, I often get the sense that I have seen this feeling of lost discontent before… on the faces of Americans.

Morocco has taught me a great deal about traditional cultures and its influences on a modern society. For Americans who feel they have a culture to identify with, tradition is expressed through the celebration of holidays, cuisine, even occasional show-and-tell at school; but most traditions seem to be mere ornamentations on the basic framework of “the American Dream”. Here it is the opposite: modernization is merely a decoration on the central pillar of tradition. It is a place where a 3000 year old language is spoken every day in the streets, a place where the old songs, names, and stories are remembered. There is even a TV station now that is entirely in Tamazight, and whose programming consists of relatable and traditional situations. Cultural pride runs deep.

You see, not all of the younger generation is ashamed and resentful of their parent culture and many of these young men (and occasionally women) that stay behind to learn from their past end up working in tourism. When most tourists come to visit Morocco, they are not here merely for the scenery. They want to see the culture. Though to some it may be like visiting a museum, westerners come here to walk the streets in the ancient medinas of Fes and Marrakech, haggling for traditional wares and eating Moroccan food; they want to sip sweet tea poured from a silver teapot, surrounded by handwoven Berber carpets and serenaded by traditional music. If they wanted to stay in a hotel room with flush toilets and basic cable, with the token print of Van Gogh’s “Starry Night” hanging over the bed, they would have stayed home. No, they come to see the real Morocco and they come in droves. In doing so they have begun to provide what the depleted environment here no longer can: a living.

In my opinion, there is still hope that even as Morocco continues to hurtle toward the future, even as the cities develop and advance to rival their counterparts across the Mediterranean; that pockets of this tradition will still remain intact; perhaps it will even spread. Looking out across my friend’s village in the pale morning light as we waited together for a taxi, it seemed to me that this way of life could go on forever and, as I looked at the large sign welcoming tourists to the valley, I smiled.I truly believe that this culture, that I will deeply love, respect, and cherish for the rest of my life; has a chance to live on intact, as vibrant and timeless as it has for thousands of years.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here and here.

.