Africa Center Org.

by Pauline Le Roux

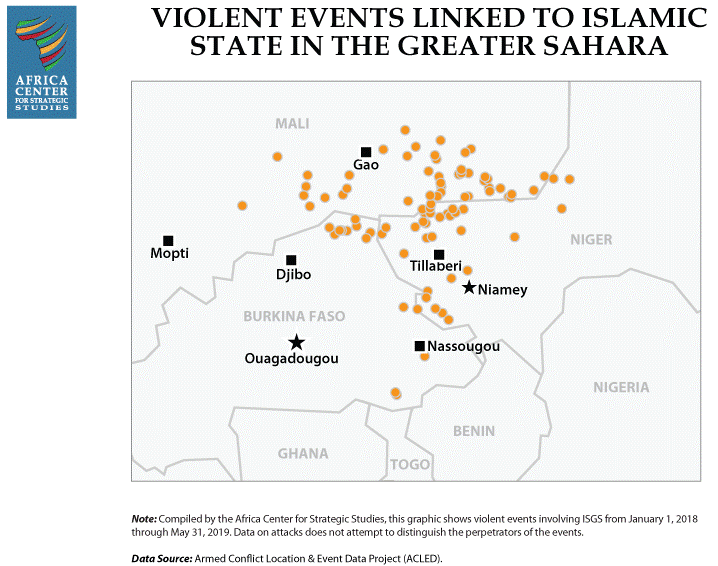

The Islamic State in the Greater Sahara has pursued breadth rather than depth of engagement in its rapid rise along the Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso borders.

The rapid escalation of violent activity by militant Islamist groups in the Sahel since 2016 has been primarily driven by three groups:

- Macina Liberation Front, focused around the Mopti-Segou region of central Mali

- Ansaroul Islam, concentrated around the Djibo municipality of northern Burkina Faso

- Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS)

ISGS has been distinctive for the geographic expansiveness of its activity, extending some 800 km along the eastern Mali/western Niger border area as well as roughly 600 km down Burkina Faso’s eastern border with Niger. Roughly 90 percent of ISGS attacks have occurred within 100 km of one of these borders.

(Click here for a printable PDF version.)

ISGS has also emerged as one of the most dangerous militant groups in the region. ISGS was linked to 26 percent of all events and 42 percent of all fatalities associated with militant Islamist groups in the Sahel in 2018. At the current pace, ISGS will be linked to over 570 fatalities in 2019, more than any other Sahelian group.

With ISGS’s push southward, worries are increasing that militant Islamist violence now threatens northern Benin, Togo, and Ghana. Two French tourists were abducted and their guide killed in early May from the Pendjari Park in northern Benin, in an attack attributed to militant groups active in the region. Two French marines died during the rescue of the hostages north of Djibo, Burkina Faso.

As a consequence of the growing violence in Burkina Faso, more than 100,000 people have fled their homes and roughly 1.2 million people are in need of humanitarian assistance. An estimated 2,000 schools are currently closedin Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso, depriving 400,000 children of an education.

The Rise of ISGS

ISGS emerged in 2015 from a fusion of pre-existing militant Islamist groups. ISGS’s chief is known as Adnan Abu Walid al Sahrawi. He was born in 1973 in Laayoune, capital of the contested territory of Western Sahara. He is the grandson of a Sahrawi chief and his family is believed to be well-connected and wealthy. Al Sahrawi was relocated into a Sahrawi refugee camp in Algeria in the 1990s. It is around that time that he joined the Polisario Front, a Sahrawi national liberation movement aiming to end Moroccan presence in the Western Sahara.

Adnan Abu Walid al Sahrawi.

During the 1990s and 2000s, little is known about al Sahrawi’s whereabouts. He is likely to have navigated between the nascent factions of militant Islamist groups that were taking root in the porous region between the Maghreb and the Sahel. He also traded with Tuareg militants of the Azawad movement in the north of Mali.

It was around this time, in 2011, that the Movement for the Unity and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO) was founded. While the three founders were previously members of al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), they wanted to create a katiba (military unit) composed of Arab fighters from the north of Mali. MUJAO’s ideology drew on references to Osama bin Laden, former Taliban leader Mullah Omar, and historical figures such as Usman dan Fodio (founder of the Sokoto Caliphate, 1804-1903), El Hadj Umar Tall (1797-1864), and Seku Amadu (who helped establish the Macina Empire in Mali, 1818-1862).

Al Sahrawi is believed to have joined MUJAO in 2012, after which he served as spokesman for the group. On August 22, 2013, MUJAO, represented by al Sahrawi, and al Mulathameen Brigade, led by the Algerian militant with strong ties to AQIM, Mokhtar Belmokhtar, announced their merger. Al Sahrawi became a key leader of the new group, al Mourabitoun.

In 2015, al Sahrawi unilaterally pledged al Mourabitoun’s allegiance to the leader of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIS), Abu Bakr al Baghdadi. Within days, Belmokhtar rejected this allegiance and reaffirmed al Mourabitoun’s loyalty to al Qaeda. Al Sahrawi broke with al Mourabitoun and formed what is now known as ISGS. Al Sahrawi’s pledge was officially recognized by Abu Bakr al Baghdadi more than a year later, in October 2016, following ISGS operations in Niger and Burkina Faso.

ISGS initially mainly operated around the city of Menaka in the Gao region of Mali, sometimes stretching as far west as the Mopti region. Although most of its original fighters are believed to be Malians from the Gao region, ISGS activities quickly extended to the Tillabéri region in Niger. In October 2017, ISGS claimed responsibility for an attack near of the village of Tongo Tongo, Niger (along the border with Mali), during which five Nigerien Special Forces and four American soldiers were killed. In 2017 and 2018, ISGS subsequently extended its activities into the Gurma region of Mali and into eastern Burkina Faso.

(Click here for a printable PDF version.)

ISGS is estimated to have a core of 100 fighters but draws on a network of informants and logistics among sympathetic villagers. In total, it may number between 300-425 members, including supporters from Niger and Burkina Faso. As opposed to other militant Islamist groups active in the Sahel, ISGS does not appear to have developed a cohesive, ideologically-driven narrative. Rather than winning people over and gaining their moral support or establishing a home base, ISGS has focused instead on stretching the battlefield. Its emphasis on mobility might explain why, despite a limited number of active fighters, it has been able to strike and remain active across the borders of three countries. The objective, in part, seems to be to strain the limited number of security forces available to patrol these expansive border areas.

Despite formally splitting from the AQIM network, ISGS continues to collaborate with al Qaeda-affiliated groups. In this way, ISGS resembles the AQIM offshoot that it is. While it draws on the ISGS name to enhance its notoriety—and ISIS benefits from the perception of an active global network—for all practical purposes, ISGS operates according to its own organizational structures, goals, and resources.

A Group Constantly Adapting to the Local Environment

Like other extremist groups such as the Macina Liberation Front, ISGS has exploited grievances of marginalized communities to recruit, especially (though not exclusively) among young Fulani men. Lack of economic opportunities, a sense of diminished social status, and the need for protection against cattle theft all apparently influence the decision to join ISGS. For instance, in the Tillabéri region of Niger, even in the absence of significant financial resources from extremist groups such as ISGS, joining an extremist group is often associated with elevated status. According to a local Fulani leader, “Having weapons gives you a kind of prestige—young people from the villages are very influenced by the young armed bandits who drive around on motorbikes, well dressed and well fed. Young herders are very envious of them, they admire their appearance.”

ISGS also stokes ethnic divisions to strengthen unity and cohesion among its members. To advance these interests, the Tuareg have often been singled out. In June 2017, al Sahrawi threatened attacks on Tuareg populations if pro-government Tuareg militias, such as the Imghad Tuareg Self-Defense Group and Allies (GATIA) and the Movement for the Salvation of Azawad (MSA), did not disavow the Malian, Nigerien, and French governments.

ISGS’s narrative shifts depending on what can garner the most support from local communities.

In 2017 and 2018, ISGS mounted several attacks against Malian civilian nomad camps, markets, and villages, primarily targeting Tuaregs. MSA and GATIA combatants retaliated by killing some Fulani herders, exacerbating tensions between Tuaregs and Fulanis in the Liptako region. In February 2018, Tuareg militias, which are members of the Platforme coalition linked to the Malian government, launched a joint offensive against ISGS in the tri-border region between Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso. The campaign reduced ISGS’s ability to operate along the border area but also increased tensions between local communities. In April 2018, ISGS is believed to have orchestrated the massacre of 40 Tuaregs from the Daoussahak tribe. This pattern of intercommunal retaliation continues.

ISGS often targets government representatives in its attacks. In 2018, ISGS claimed responsibility for the killing of the mayor of Koutougou commune because he was working “with Burkina’s armed forces, for the crusaders.” Starting in 2018, ISGS has also repeatedly targeted schools, with devastating effect. Over 1,100 schools have been shut down in Burkina Faso after threats, attacks, and the murders of teachers and administrators. ISGS is now linked to nearly 30 percent of all militant Islamist attacks in Burkina Faso, sharply contributing to the escalating Islamist insurgency in the country.

Given that it plays on ethnically-based and anti-government grievances, ISGS’s narrative shifts depending on what can garner the most support from local communities. For example, despite provoking Fulani confrontations with Tuaregs in Mali, ISGS convinced Fulanis in Niger that the enemy was “not actually the Tuareg but the state.” This included a January 2018 raid targeting Operation Barkhane. In May of 2019, Islamist militants attacked a high security prison in Koutoukalé, 45 km north of Niamey. Nigerien troops who were pursuing the militants were subsequently ambushed near Tongo Tongo, not far from the Mali border. Three dozen Nigerien soldiers were killed in the incident for which ISGS claimed responsibility. ISGS characterized the ambush as an attack against an apostate military along the artificial border of Mali.

Responses against ISGS

Despite reports that al Sahrawi was injured and forced to relocate in 2018 following clashes with Tuareg militias GATIA and MSA, ISGS’s pace of attacks has not abated. Pressure on the group has grown, however. In May 2018, the United States placed ISGS on the list of foreign terrorist organizations, and al Sahrawi was designated a global terrorist by the U.S. Department of State. Operation Barkhane has increasingly targeted ISGS’[s] members, imposing a growing military toll on the group. The G5 Sahel Joint Force, established in 2017, aims to fight militant groups in the border areas, notably in the Soum province in northern Burkina Faso. The operationalization and deployment of this force is still in process, however.

In August 2018, Sultan Ould Bady, the Malian head of Katiba Salaheddine and allied to ISGS, surrendered to Algerian authorities under pressure from counterterrorism efforts targeting ISGS leadership. Later that month, Barkhane announced that Mohamed Ag Almouner, one of al Sahrawi’s most important lieutenants who was believed to have orchestrated the 2017 Tongo Tongo attack, had been killed in a raid. Nonetheless, ISGS has been resilient.

In Burkina Faso, the security apparatus is having to adapt to the sudden escalation of ISGS activity. It is widely believed that former president Blaise Compaoré had negotiated nonaggression pacts with extremist groups in an attempt to preserve Burkina Faso from attacks. His sudden departure from office required a major reorganization of law enforcement agencies. In October 2017, a National Security Forum was launched by newly elected President Roch Marc Christian Kaboré in order to reform and reorganize the security sector.

In June 2017, a 3-year emergency fund program for the Sahel region of Burkina Faso of 455 billion CFA (about $778 million) was setup with the objective of improving local and administrative governance. Intended as a holistic response targeting the intersection of socioeconomic and security challenges, this plan aims to fund new infrastructure, the expansion of public services (health care centers, police stations) and support for resilient agriculture projects. In 2018, about $265 million was secured for priority investments.

Importantly, many Sahelian countries already have the bilateral and multilateral agreements in place to improve security cooperation. For instance, Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger are all part of the 1992 Legal Assistance Convention in criminal matters, the 1994 Extradition Convention, and of the 2012 Charter for Sahel Countries Judicial Cooperation.

The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) has similarly undertaken a wide range of initiatives in order to strengthen cross-border cooperation in border management. Several international organizations such as INTERPOL and the International Organization for Migration have also supported Burkinabe authorities by launching border management and control programs and supporting the installation of more effective police information collection and management systems.

While promising in their holistic approach and regional scope, the impact of these initiatives often remains muted due to limited human, financial, and institutional resources. These undertakings, therefore, will need to be enhanced and sustained over time. In the meantime, keeping pressure on ISGS will require further strengthening of local, national, regional, and international alliances along the borders where they have thrived.

Additional Resources

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “A Review of Major Regional Security Efforts in the Sahel,” Infographic, March 4, 2019.

- Pauline Le Roux, “Confronting Central Mali’s Extremist Threat,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, February 22, 2019.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “The Complex and Growing Threat of Militant Islamist Groups in the Sahel,” Infographic, February 19, 2019.

- Terje Østebø, “Islamic Militancy in Africa,” Africa Security Brief, No. 23, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, November, 2012.

- Helmoed Heitman, “Optimizing Africa’s Security Force Structures,” Africa Security Brief, No. 13, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, May 2011.