The Wall Street Journal

By Brooke Anderson

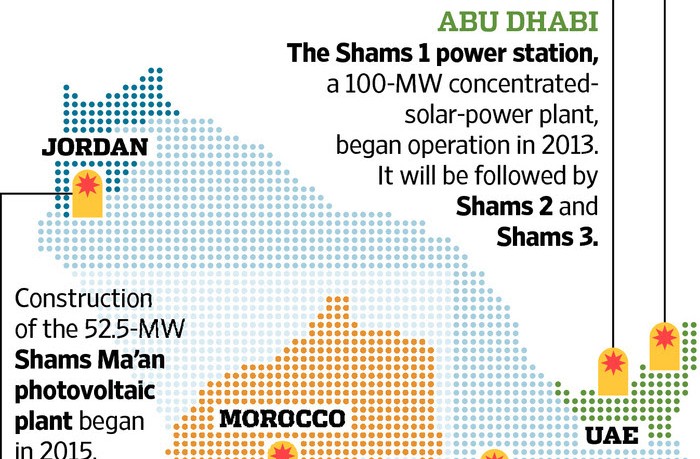

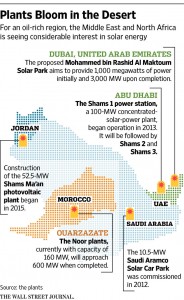

When completed, the Noor-Ouarzazate station will be capable of generating enough electricity for more than a million people.

The rugged landscape around Ouarzazate, a city in south-central Morocco on the edge of the vast Sahara, is known to some as a filming location for movies such as “Lawrence of Arabia” and television shows like “Game of Thrones.” Now, the sparsely populated area is getting attention for something else: solar power.

The first phase of a $9 billion solar-power project that has been under construction since 2013 opened earlier this year, making use of vast arrays of mirrors, rather than the more widely used photovoltaic panels, to produce electricity from sunlight.

When it is finished in 2018, the Noor Solar Power station will cover more than 5,000 acres and have a generating capacity of 580 megawatts, enough to meet the electricity needs of 1.1 million Moroccans, according to the World Bank, which is helping to fund the project. It will be one of the largest solar power plants in the world, rivaling BHE Renewables Solar Star project in Southern California, which claims a capacity of 586 megawatts.

“This makes Morocco a big pioneer in the field of solar energy in the Arab region and the African continent,” says Ali Hajji, a Moroccan solar-energy specialist and engineering professor at IAV Hassan II in Rabat, Morocco. “It could also be a pioneer for many other countries in the world that depend on foreign imports for energy.”

The Noor project is coming online at a time when demand for energy in Morocco is increasing at about 7% a year. The nation, which currently depends on imports for more than 90% of its energy needs, including transportation, expects the solar plant to play a key role in an effort to generate 50% of its power from renewable sources by 2030.

The project’s first phase, which launched in February, has a generating capacity of 160 megawatts.

While many other utility-scale solar projects are based on photovoltaic technology, Noor uses concentrated solar power, or CSP, to turn sunlight into electricity. Curved mirrors concentrate the sun’s rays on pipes running down the middle of troughs, heating a synthetic oil inside. The hot fluid boils water, generating steam that turns a turbine to generate electricity. Excess heat from the fluid is then stored in molten salt, making it possible for the plant to continue generating electricity hours after the sun goes down.

Although a relatively minor part of the energy mix today, CSP could account for 11% of the world’s electricity needs by 2050, according to projections by the International Energy Agency.

That said, some experts question the viability of large-scale CSP projects in the wake of price drops for photovoltaic panels—and the batteries that many expect eventually will be used for utility-scale storage. While the average price of a CSP project fell to about 12 cents a kilowatt hour in 2015 from around 21 cents in 2010, according to a U.S. Energy Department estimate, the average price of a utility-scale photovoltaic project declined to about 10 cents a kilowatt hour in 2015 from 21 cents in 2010.

“CSP electricity is still relatively expensive compared with PV, whose price has dropped by more than half since 2008,” says John Farrell, director of the energy democracy initiative at the Institute for Local Self Reliance, a Washington, D.C., nonprofit devoted to promoting environmentally sound community development.

Supporters counter that CSP’s ability to make energy when the sun isn’t shining is a big advantage that ultimately gives it a cost edge.

“How the future plays out between CSP with storage and cost reductions for electric batteries is one of the more interesting unknowns related to which technologies will provide the best balance of flexibility and costs in future sustainable electricity systems,” says Michael Taylor, a senior analyst at the International Renewable Energy Agency based in Abu Dhabi.

Regardless of the solar technology used, energy experts see the Middle East/North Africa region as an important frontier for utility-scale solar projects like Noor. The area is blessed with abundant sunlight, and improvements in solar-power technology and steadily falling prices have made it more economically feasible to exploit solar for power generation in the region.

In addition to solar plants already operating in places like Abu Dhabi and oil-rich Saudi Arabia, there are even more ambitious projects in the works, including the proposed Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum Solar Park in Dubai, which aims to provide 1,000 megawatts of power initially and as much as 3,000 megawatts upon completion.

“The last few years have seen a realization of just how competitive solar technologies can be,” Mr. Taylor says. The potential for the Middle East/North Africa region, he adds, “is enormous.”

Morocco, because it lacks the deep pockets of some of its oil-rich neighbors, relied on a coordinated financing arrangement to help pay for the Noor project. A government agency set up to manage and gather financing pulled together a group of international institutions, including the World Bank and the European Union, as well as German and Saudi companies. In addition, the agency took about a 25% ownership stake in the project.

“It’s remarkable they’ve been able to make it happen within the time and budget,” says Katharina Böhme, energy project manager with KfW, a German investment bank that provided loans for the Noor project.

Ms. Anderson is a writer in Beirut. She can be reached at reports@wsj.com.