Institut Montaigne

With nearly 6,500 cases reported as of May 13, Morocco is the third African country most affected by Covid-19. Considered a model of Covid-19 crisis management, especially by its neighbours, Morocco has not spared any resources in dealing with the crisis, especially financial ones. While the total lockdown of the country is not expected to be lifted before May 24, several recovery scenarios are being considered by the authorities. What is the current health situation? What are the economic impacts of the crisis in Morocco? What is the exit strategy from the crisis?

Larabi Jaïdi, Senior Fellow at the Moroccan think tank Policy Center for the New South, gives us his analysis.

What is the current health situation in Morocco? How could it evolve in the coming weeks?

The government’s analysis in the aftermath of the first signals of the Covid-19 epidemic indicated that Morocco was at risk of rapid exposure to the epidemic. Morocco is not far away from the European continent (15 kilometres), and it is open to the rest of the world through its trade in goods and services and human movements. Moreover, a large Moroccan diaspora resides in Spain and Italy, and the country is an air hub between Northern and Southern countries.

The Ministry of Health’s report, as of May 11, reveals a cumulative total of 6,418 cases and 188 deaths. 64,299 people tested negative. The morbidity rate remains stable at 2.9%. As a result of the measures taken, 6,000 deaths have been averted. The total number of recoveries is 2,991. The number of critically ill patients treated remains stable, with 81 cases in intensive care or resuscitation unit. Only 5% of the 1, 600 intensive care beds are used. The frequency of laboratory tests for suspected coronavirus cases has increased from less than 1,000 to more than 2,000 tests per day.

Of the new confirmed cases of Covid-19, 80% are from the follow-up of contact cases. A large majority of these come from family and professional contamination (companies and shopping centres). The appearance of family outbreaks is explained by the fact that people live together in small areas, making isolation difficult. The extension of the state of sanitary emergency reflects the desire to remain vigilant in monitoring the epidemic, in order to avoid the resurgence of clusters even if the R0 (virus production rate) has fallen. It used to be 3, and it is now it is less than 2. De-confinement is likely to take place gradually, following the epidemiological situation in the different regions. A strategy is currently being developed and several scenarios are being studied. Its modalities will depend on scientific data regarding the nature of the virus, the infrastructure of hospitals, the protection capacity of the economy and the purchasing power of consumers.

What is the strategy adopted by the authorities to combat the epidemic?

On March 25, a Special Fund for the management of the pandemic of 10 billion dirhams (934 million euros) was deployed.

Measures were rapidly implemented to minimise the scope of the containment chain: “Coronavirus command posts” have been set up at the appropriate territorial levels to monitor and coordinate the identification and location of the epidemic with the health services. This initiative was reinforced by closing borders, prohibiting gatherings, closing schools, and drastic measures encouraging voluntary and then compulsory lockdown.

The Ministry of Health has implemented a series of measures to raise its level of vigilance in monitoring the epidemiological situation in real time. It has adjusted its mode of operation by setting up a Technical and Scientific Advisory Committee, one of whose missions is to define a protocol for the care of patients with Covid-19. At the same time, on March 25, a Special Fund for the management of the pandemic of 10 billion dirhams (934 million euros) was deployed. Initially endowed with budgetary resources, and later supplemented by private and public contributions, the Fund was to be used to finance expenditure on medical device upgrades, to support the national economy in coping with the shock, to preserve jobs and to mitigate the social impact of the pandemic. An inter-ministerial monitoring committee steered the economic and social components of the action plan.

A monthly allowance is granted until the end of June 2020 to employees of struggling companies, who have temporarily stopped working and are registered for the National Social Security Fund (CNSS). So far this includes 132,000 out of the 216,000 companies affiliated to the Fund, and nearly 900,000 employees. The latter also benefit from extensions in the repayment of consumer and housing loans. Cash transfers were made to 2.3 million households affiliated to the Medical Assistance Scheme, of which 38% were from rural areas. These transfers were extended to the population working in the informal sector and not benefiting from the Assistance Scheme, i.e. 2 million households. Thus, 4.3 million families working in the informal sector can benefit from the support of the Covid-19 special fund.

The Monitoring Committee has taken a series of measures in favour of businesses affected by this pandemic, in particular VSEs, SMEs and self-employed professionals. It has granted extensions of bank and leasing credits (310,000 applications), and granted credit insurance to companies whose cash-flow has deteriorated (9,000 loans). Other measures have helped ease the financial constraints of companies: deferral of tax returns, suspension of tax inspections, tax exemption, easing of late payment penalties on public contracts, interest-free loans to self-employed entrepreneurs. The Monitoring Committee has also introduced several measures to facilitate the financing of the economy by the banking system in order to meet the liquidity needs of businesses. Banks have been invited to postpone provisioning for loans that will be subject to a moratorium and to use liquidity cushions after a loosening of prudential ratios.

Does the population support these measures?

Today, the population is aware of the gravity of the risk and follows public directives more diligently. The State’s calls to respect barrier measures, social distancing, hygiene standards, and the wearing of masks have found a favourable response among the majority of citizens.

The speed at which the virus spread has gradually led the authorities to adopt more restrictive measures, limiting people’s mobility. A health emergency law was enacted, and lockdown was imposed. All of the State’s resources were mobilized: communication to the citizens, security forces, sanctions for breaking the law. This balance between communication, deterrence and punishment has fostered a more responsible attitude from those who initially seemed reluctant to see their freedom of movement infringed upon.

The State’s calls to respect barrier measures, social distancing, hygiene standards, and the wearing of masks have found a favourable response among the majority of citizens.

8,612 people have been arrested and subjected to judicial investigations since the declaration of the state of sanitary emergency in Morocco, for various reasons: lack of exceptional transport authorization, violation of the imposed measures, dissemination of false digital information about the epidemic and incitement to disobey security measures etc. In the meantime, the credibility of the communication plan aimed at the public has strengthened public support. This plan has included an awareness-raising campaign by the media, information on health monitoring, production of information kits, development of educational materials, and a digital community platform. Surely the population was also reassured to see the “protective” state moving quickly and effectively to provide assistance in the form of cash transfers to vulnerable people affected by the loss of jobs, following the closure of thousands of businesses, or by the impact of the lockdown on informal survival activities for thousands of households.

Echoing this vertical solidarity carried out by the State, other actions of solidarity of a horizontal nature have been undertaken by economic and social actors. Social companies (public and private) have set up hospital services and consultation centres. Hotels and catering units have volunteered to provide accommodation and catering services for patients or health personnel. Voluntary work has taken the form of various actions: setting up networks of suppliers who donate food, mobilizing students from specialized hotels and catering schools, bringing together citizens and professionals who work in the field of events and artistic production. University researchers were also involved in the development of mathematical models for predicting the spread of Covid-19 in Morocco.

The State has sought to ensure the continuity of public services by organizing locally and by including regional authorities, to enable the maintenance of vital activities, the regular monitoring of market supply and operations to control the price and quality of food products. This has strengthened the population’s confidence in the State’s ability to manage this crisis.

Is the healthcare system resilient enough to deal with the epidemic?

Morocco has one of the best healthcare infrastructures in Africa, albeit below expectations of what a diversified and territorially-balanced coverage should be. The health sector in Morocco has shortcomings, particularly in terms of services provided to citizens which remain insufficient and unsatisfactory for the population. Despite the efforts made by the public authorities, the health system still suffers from numerous dysfunctions and a lack of human resources.

Morocco has one of the best healthcare infrastructures in Africa, albeit below expectations of what a diversified and territorially-balanced coverage should be.

The overall density of health professionals in Morocco is 1.9 per 1,000 inhabitants, whereas the WHO threshold for achieving universal health coverage by 2030 is 4.45. The ratio of beds per capita in the public sector is 0.6, compared to an average of 7 in OECD countries. This problem is compounded by disparities in coverage between and within regions. The public and private sectors are developing in a non-complementary manner. Health expenditure weighs heavily on household budgets, which bear 54% of the cost. One third of the population (mainly self-employed workers) does not benefit from health coverage.

Realistic about its limited health resources (especially its bedding capacity) and aware that the pandemic was evolving at a high speed, Morocco had to be very responsive by deploying a multi-level action plan. The resources of the fund earmarked for the health sector were used mainly to purchase medical and hospital equipment, medicines and medical consumables, and to strengthen the Ministry of Health’s operating resources. The latter has taken initiatives to increase and redevelop hospital capacity and improve admission facilities for patients in various cities in Morocco, particularly those with high human density and the highest risk exposure.

Military field hospitals have been deployed in and around towns to reinforce the civilian healthcare system with intensive care beds and equipment. Batches of medical and sanitary equipment were imported promptly and deployed to health facilities. Stocks of medicines have been built up, in particular chloroquine produced by a pharmaceutical group based in Morocco. Moroccan companies specializing in the manufacture of medical equipment (including ventilators) were also called upon through accelerated procedures. Other companies have been able to readapt their production facilities to produce ventilators and secure the production of masks.

The Ministry of Health has emphasized early detection: the definition of “suspicious cases” to identify contaminated persons has been subject to successive revisions. Once imported outbreaks had been eliminated, vigilance turned to internal clusters. The Ministry gradually strengthened its screening capacity by scheduling the purchase of screening kits and acquiring various rapid diagnostic tests. The territorial coverage of tests and analyses has been extended to include University Hospital Centres (CHU) in various regional metropolises and military hospitals. Finally, free access to care has been ensured, from screening tests to hospital admissions, or even to a hotel if patients have to be isolated.

What will the economic impact of coronavirus be in Morocco?

The growth outlook for the national economy has been revised downwards. It should be cut by 8.9 points in the second quarter of 2020. Forecasts of foreign demand for Moroccan exports are also down, following the expected decline in imports from the Kingdom’s main trading partners. The decline in foreign demand will be accompanied by a decline in domestic demand as the period of lockdown extends into more than half of the second quarter. Household consumption growth is expected to decline by 1.2% in the second quarter of 2020. Investment is projected to continue to decline at a rate of -26.5% compared to the second quarter of 2019, reflecting increased destocking of companies.

A survey by the Haut Commissariat au Plan (the national statistics institute) found that nearly 142,000 businesses, or 57% of all businesses, reported that they had permanently or temporarily ceased all activity. The hospitality and catering industries are the most affected by the crisis, with 89% of companies at a standstill, followed by the textile and leather industries (76 %), the metal and mechanical engineering industries (73%) and the construction sector (60%). This situation would have an impact on employment. In fact, 27% of firms are reported to have reduced their workforce temporarily or permanently, i.e. almost 726,000 jobs or 20% of the workforce of organised firms. These losses concern 21% of VSEs, 22% of SMEs and 19% of large enterprises. More than half of the reduced workforce (57%) are employees of VSMEs (very small, small and medium-sized enterprises).

The preliminary results of a CGEM (Employers’ Confederation) survey also reveal the violent impact of Covid-19: 47% of companies saw their quarterly activity fall by more than 50%. 78% of tourism businesses report a drop in employment, and two thirds of them a fall in turnover. The decline is seen almost everywhere: property developers, craft industry, cultural and creative industries, media, textiles…

57% of all businesses, reported that they had permanently or temporarily ceased all activity.

Businesses affected by the crisis have requested extensions for banks (41.8% of respondents), tax (37%) or deposit (33.7%) payment deadlines. Nearly 23% of the companies surveyed requested all three extensions. The businesses surveyed fear the loss of 165,586 jobs, or 55.11% of their workforce. Businesses that have recorded a drop in turnover of more than 50% fear the loss of 100,000 jobs. The survey points out that 39.2% of companies are in temporary shutdown and 88% have resorted or are likely to resort to temporary shutdown. Most companies expect a gradual recovery from June onwards, but turnover, to varying degrees, will remain impacted throughout the year. Those most affected over time appear to be tourism, real estate and then textiles.

Are the decision-making bodies already thinking about the future? What exit strategies are being considered? What are your recommendations in this regard?

There is still a lot of uncertainty as to when this crisis will end. The date will be neither global nor immediately after the end of the health crisis. Moreover, this ending of the crisis is not yet fully visible. Many uncertainties about the economic cost that the country will have to bear in the medium term remain. In spite of these uncertainties, the Monitoring Committee has begun its first reflections on the exit strategy, its modalities, its means, the coherence of the sequences of articulation between the short and medium term, etc. The Committee has also begun to examine the possibility of a new approach for the country’s economic development.

The Committee’s initial reflections indicate that an exit plan from the crisis will be announced shortly. Scenarios are being developed, taking into account the sectors’ capacity and speed of recovery, the financial health of companies, priorities, etc. The Committee will have to decide on a series of actions and trade-offs: which sectors should be given priority? Which are those related to covering demand for essential needs (food, health and transport in particular)? Which can respond to the recovery of external demand and are able to help rebuild the foreign exchange reserve portfolio?

Beyond the ranking of priorities, mobilizing action levers in an effective and optimal way is a crucial aspect of the Committee’s agenda. A stimulus induced by supporting household demand and by encouraging supply through investment must be considered. In this challenge, the question of sustainable financing is crucial. Recovery through budget and public procurement will be confronted with the reduction of regular resources, a widening budget deficit and a tolerable debt threshold. Parliament has authorised the government to exceed the debt ceiling in the 2020 budget law. The use of the precautionary and liquidity line (amounting to 3 billion dollars to be repaid over a period of 5 years, with a grace period of 3 years) negotiated with the IMF at the end of 2018 will make it possible to mitigate the effects of this crisis, and to preserve foreign exchange reserves, thereby consolidating the confidence of foreign investors and of Morocco’s bilateral and multilateral partners. This insurance against extreme shocks does not affect the level of public debt. Nevertheless, if the budget deficit exceeds a sustainable norm, it will be necessary to finance the debt through other lines of credit from financial institutions, or to resort to the capital market without falling into a restrictive conditionality regime that would call into question the country’s financial sovereignty.

The other financing option is linked to the capacity of the Moroccan banking system to provide the necessary liquidity to companies which, beyond their cash requirements, are likely to face a solvency crisis requiring a strengthening of their balance sheet In this challenge of credit financing, the national financial system, which has proven its financial soundness, will be faced with the need to support businesses with greater imagination and responsiveness, less conditionality on guarantees and rigidity in the release of resources, while ensuring that its financial stability is preserved.

The success of the exit strategy will depend upon the optimal combination of a policy mix of a sustainable fiscal policy and a flexible monetary policy.

Today, monetary and credit policy is called upon to be more flexible, ensuring the fundamentals of inflation and exchange rate equilibrium, while accompanying the economic recovery with an appropriately balanced use of conventional and non-conventional techniques. The success of the exit strategy will depend, in this respect, on the optimal combination of a policy mix of a sustainable fiscal policy and a flexible monetary policy.

What lessons will Morocco be able to draw from the crisis – in terms of digitalisation of public services, for example?

Covid-19 forced the administration to go digital. One of the lessons of this health crisis is that the digitalisation of some ministerial departments has made it possible to guarantee the continuity of services essential to the life of citizens. For instance, working from home, or limiting the physical exchange of administrative and official documents. The Digital Development Agency (ADD) has supported these measures by developing digital platforms that comply with standard technical practices in this area. The “digital order desk portal”, which facilitates the electronic management of incoming and outgoing mail flows, the “electronic mail counter” with the automation of the mail processing system within a given administration, and the “electronic signature”, which allows complete dematerialisation of document flows, are just a few examples. Several ministries, local and regional authorities, public institutions and companies have adopted teleworking. This opportunity should be seized to institutionalize this system by giving it a legal basis.

Online banking services, the distribution of financial aid, distance learning in schools and universities, teleworking in companies, telemedicine, are all practices that have been embraced during this crisis and that should be continued.

However, the VSEs and SMEs are the first to suffer from the lack of digitalisation in Morocco. While citizens and consumers are generally comfortable with digital tools, many SMEs and VSEs are struggling to make their own digital revolution due to a lack of digital culture and skills, insufficient financial support, territorial digital divide, ambivalent relations with online platforms. This is alarming given that they represent 99% of Moroccan companies.

This context of this health crisis shows that both large and small businesses need to develop some form of flexibility. The goal is to establish a real, long-term strategy around the company’s digital tools. Digital technology would then no longer represent a barrier but rather a step in a process of transformation. The APEBI (Moroccan Federation of Information Technologies, Telecommunications and Offshoring) has recently taken action by launching calls for innovative projects aimed at start-ups, VSEs, SMEs, universities, NGOs, local experts, etc…

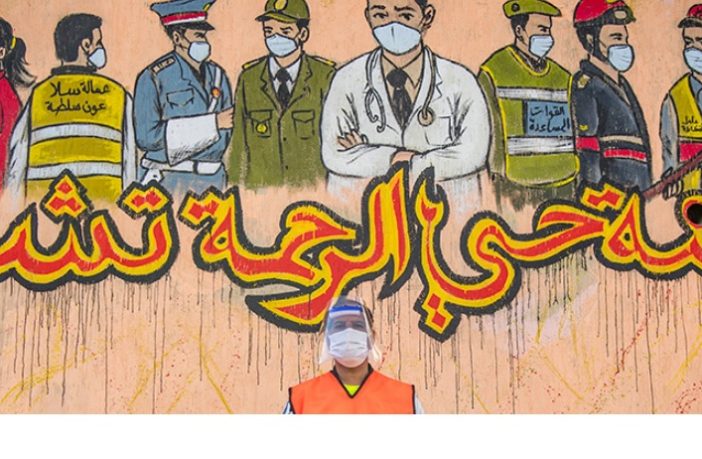

Copyright : Fadel SENNA / AFP

Larabi Jaïdi

Senior Fellow at the Policy Center for the New South