The New York Style Magazine

By Thessaly La Force

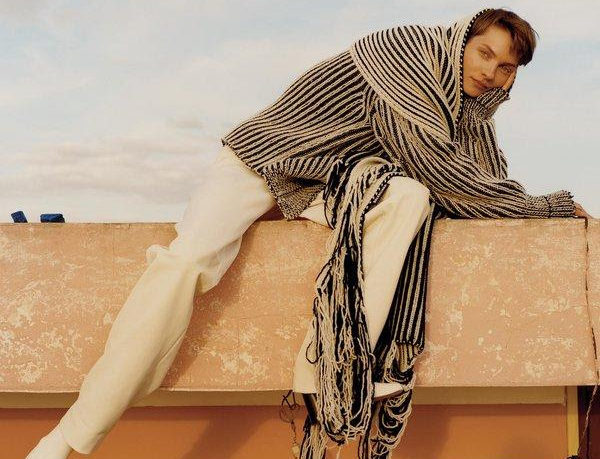

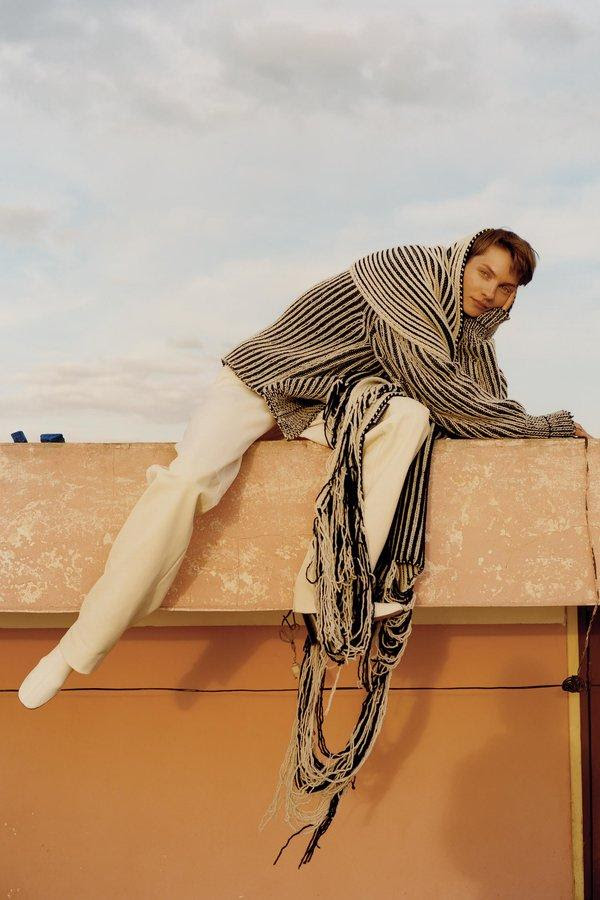

The author’s classic travelogue unfolds in golden Marrakesh, and takes shape here in adventure-ready khakis, creams and camels.

In 1920, Edith Wharton published “In Morocco,” a detailed account of her time spent traveling through the region with Hubert Lyautey, who served as the resident general of French Morocco from 1912 to 1925. By the end of the First World War, Morocco was still a colonial entity, divided between French and Spanish powers (the country would claim independence in 1956).

There were no English-language guidebooks and few accounts from those who had traveled past the international port city of Tangier (“frowsy, familiar Tangier, that every tourist has visited for the last forty years,” Wharton complained in her book). It’s difficult to imagine a Morocco so unknown to such fashionable Western society — Wharton, who kept company with dukes and duchesses and Teddy Roosevelt, and who ran in the same circles (and traveled through much of Europe) with her dear friend, the American writer Henry James, was not writing about the same place that has become so well exoticized since by everyone from Yves Saint Laurent to Marella Agnelli.

I Dreamed of Africa

Few women traveled as Wharton did, and even fewer wrote about their journeys with such clarity and beauty — then or now. She is well known for her novels, including “The Age of Innocence” (which won the Pulitzer Prize in 1921) and “The House of Mirth” (1905) — both grand, moral tales of the elite echelons of New York society during the Gilded Age — but Wharton, who died in 1937, has often been, as the biographer Hermione Lee writes in The New York Review of Books, “downgraded as a reactionary, an antimodernist, a rich old-school genteel snob and a minor female version of Henry James.”

In the last 50 years, much more attention has been given to the parts of Wharton’s life that don’t fit as neatly into her larger successes: her lesser-known fiction; her work on interiors, landscaping and architecture; and her travel writing.

Which brings us back to Morocco. General Lyautey’s immense power allowed Wharton to travel in luxury and without much fear. It also provided her with access to places few other tourists were allowed to trespass, including the imperial palace of Sultan Youssef in Rabat and the holy city of Moulay Idriss, which until as recently as 2005 did not allow non-Muslims to stay overnight. By boat and motor and mule, she traveled from Tangier to Rabat to Salé to Fez to Marrakesh, and in her writings there is the indelible self-awareness that she is embarking on a great adventure.

There are exquisite, transporting descriptions of the different cities. She writes of “glimpses of sea and plain through the lattices of the gallery,” she describes gowns the colors of peach blossoms and lilac, and a little girl wearing a “jewelled diadem” over “pearl-woven braids.”

Her eye for material details is wonderfully vivid and precise: “Marble floors, heavy whitewashed piers, prostrate figures in the penumbra, rows of yellow slippers outside in the sunlight — out of such glimpses one must reconstruct a vision of the long vistas of arches, the blues and golds of the mirhab, the lustre of bronze chandeliers, and the ivory inlaying of the twelfth-century minbar of ebony and sandalwood.”