European Council on Foreign Relations

Fatim-Zohra El Malki & Anthony Dworkin

SUMMARY

European countries have worked closely with Morocco and Tunisia on security, providing training and equipment for counter-terrorism and conducting some joint operations with Morocco.

Tunisia’s security services have improved significantly since the country’s high-profile terrorist attacks in 2015. Although it has been slow in reforming the police, Tunisia is at least open to engaging with international partners on reform.

- Morocco presents itself as a capable security partner that closely monitors its population and controls its religious sphere. But it relies on a repressive political system and resists outside calls for reform.

- Both countries face problems in handling radicalised individuals – and they have failed to develop systematic approaches to curbing radicalisation and addressing conditions that facilitate it.

- European states, especially EU members with close ties to Morocco and Tunisia, should devote more effort to joint work on radicalisation, and look for further opportunities to address socio-economic marginalisation and improve security governance, in both countries.

INTRODUCTION

In the last few years, security and counter-terrorism have become increasingly important to European Union countries’ policies on north Africa. This trend reflects growing European concern about the influence of the Islamic State group (ISIS) and other terrorist organisations in the region, the large number of foreign fighters from north African countries who have joined conflicts there and in the Middle East, and the north African connections of terrorists who have carried out attacks within Europe. European countries have a strong interest in understanding security threats that emanate from north Africa, and in working with north African countries to address them.

Although terrorists and weapons have regularly crossed the borders of north African countries, national boundaries continue to have a major effect on the fight against terrorism. Due to the near-total breakdown of the Libyan state, terrorist groups have established a larger presence in Libya than any other north African country. But, for the EU, another vitally important arena is found in North African countries that have functioning states with whom the EU can work, yet that are nevertheless fighting against security threats, including high levels of terrorist recruitment domestically. Tunisia and Morocco stand out in this respect: both countries have close links to the EU and its member states, and are engaged in significant campaigns against terrorism and radicalisation targeting their domestic and diaspora populations. Together, they make up the front line in the EU’s efforts to establish zones of security on the southern shore of the Mediterranean.

This study analyses the nature of security challenges in Tunisia and Morocco, these countries’ efforts to counter terrorist groups, and security cooperation between them and the EU and its member states. Tunisia’s and Morocco’s distinct histories and capabilities shape their differing approaches to the fight against violent extremism, and therefore EU states’ options in working with them. Nevertheless, the countries’ counter-terrorism strategies share a common shortcoming: both Morocco and Tunisia have prioritised the prevention of attacks and the disruption of terrorist cells, but have failed to pay sufficient attention to the legal and judicial framework for handling people detained on terrorism charges – or to the wide range of factors that contribute to radicalisation. Granted, these are complex problems that EU countries are struggling to address at home. However, the EU should supplement its current focus on technical and operational security assistance with greater attention to areas such as the treatment of arrested suspects, socioeconomic factors that may contribute to radicalisation, and the state’s broader relationship with communities that are disproportionately vulnerable to terrorist recruitment.

The evolution of terrorism in the Maghreb

Islamist terrorism has a long history in the Maghreb. During the 1980s, hundreds of fighters from the region travelled to Afghanistan to battle the forces of the Soviet Union. In Algeria during the 1990s, the Groupe Islamique Armé (GIA) and other jihadist organisations waged a ferocious campaign against the state that killed tens of thousands of civilians. By the end of the decade, these groups had been beaten back. But the subsequent rise of al-Qaeda and the global reverberations caused by 9/11 led to an evolution in jihadism in the Maghreb.

Islamist groups in the region increasingly forged transnational links. In 2002, a group with ties to al-Qaeda (and apparently directed from Paris) killed 21 people by detonating a truck bomb at a synagogue in Djerba, in Tunisia.[1] In 2003, attackers inspired by, and perhaps linked with, al-Qaeda conducted a series of coordinated suicide bombings in the Moroccan city of Casablanca, killing 45 people. In Algeria, a GIA splinter group declared its allegiance to al-Qaeda, rebranding itself as al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) in 2007, before carrying out a series of suicide attacks that year aimed at political, international, and other targets in Algiers.

Tunisia, Morocco, and Algeria reacted strongly to this wave of terrorist attacks. The Casablanca bombings came as a shock to Morocco’s authorities and citizens, contradicting the idea that the country’s monarchy made it immune to Islamist extremism. Morocco quickly passed new counter-terrorism legislation that broadened the definition of terrorism and gave greater powers to the security services (including the power to hold suspected terrorists for up to 12 days without granting them access to a lawyer), and prosecuted and imprisoned several hundred people for their alleged links to Islamist extremism.[2] Tunisia also passed a tough new counter-terrorism law and imprisoned large numbers of people. In Algeria, the regime dismantled jihadist cells in Algiers and pushed AQIM’s leadership into the mountainous region of Kabylia, while driving the group to shift its operational focus to the southern Sahara and Sahel region. In all these cases, the government’s use of repression limited the domestic impact of terrorism, even if there continued to be some attacks for several years afterwards.

Terrorism in the Maghreb underwent a new stage of evolution following the Arab uprisings that began in late 2010. In Tunisia, the transition from repressive authoritarianism to post-revolutionary confusion allowed for a sudden resurgence of Islamist extremism. One of several Salafi jihadists to receive amnesty and be released from prison in early 2011 subsequently established Ansar al-Sharia in Tunisia (AST). While AST initially focused on proselytising, recruitment, and the promotion of public morality, it also appears to have quickly acquired weapons and established a military wing.[3] One militant who had links to AST at this time later claimed responsibility for the killing of two prominent leftist Tunisian politicians in 2013.[4] The breakdown of public order in Libya following the overthrow of Colonel Muammar Gaddafi also provided the group with a useful base from which to conduct training and obtain weapons. Tunisia designated AST as a terrorist group in August 2013, prompting a decline in its influence as many of its members were arrested or fled the country. Meanwhile, jihadist group the Oqba Ibn Nafaa Brigade, an AQIM affiliate, established itself in the mountainous Chaambi region, near Tunisia’s border with Algeria, where it engaged in sporadic clashes with Tunisian security forces.

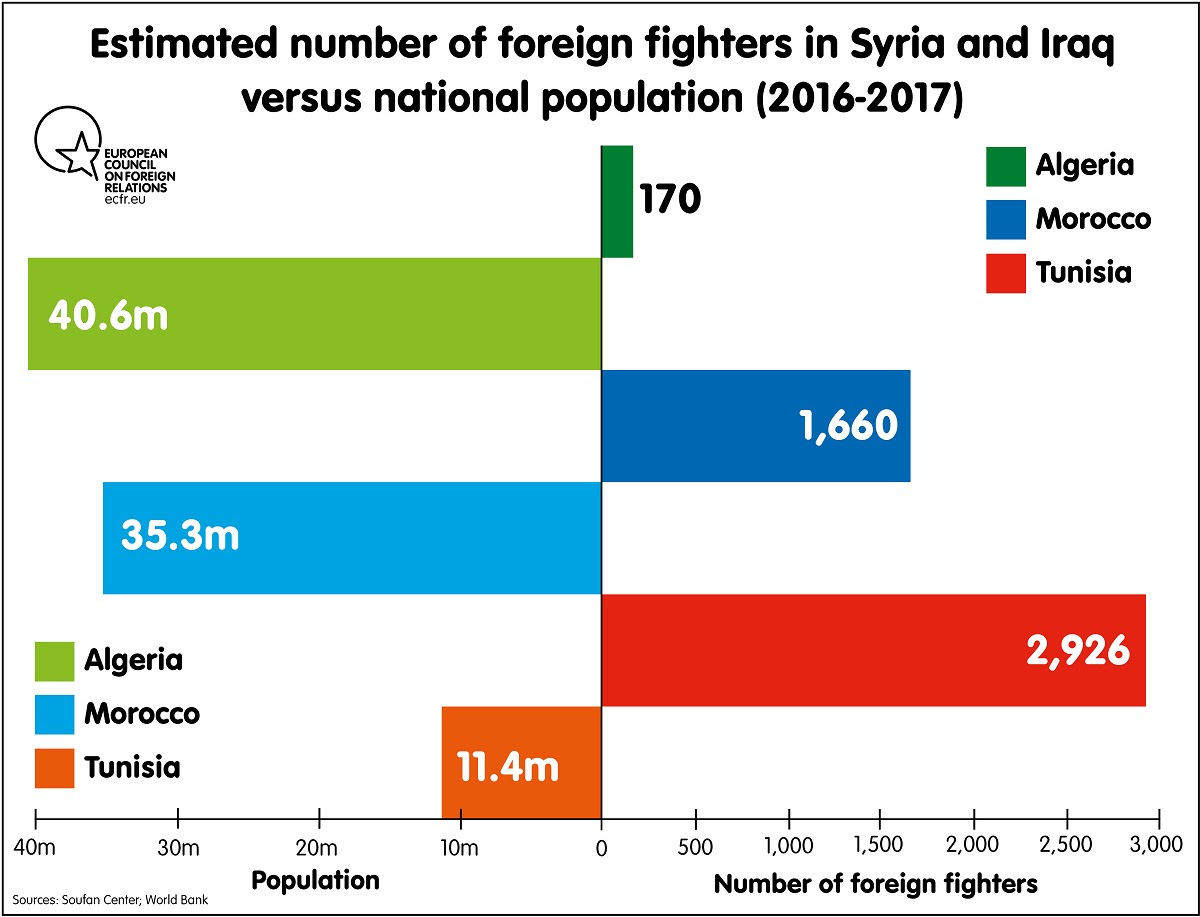

Morocco last experienced a major terrorist attack in April 2011, when a bombing in Marrakech killed 17 people. Nevertheless, there have been many Moroccans among the foreign fighters who subsequently joined jihadist groups such as ISIS in Syria, Iraq, and, later, Libya. According to the Moroccan government, more than 1,600 Moroccans went to fight in Syria and Iraq.[5] These figures are exceeded by Tunisia, which has provided around 3,000 foreign fighters in Syria and Iraq (and perhaps significantly more) out of a much smaller total population. While there is now some doubt about claims that Tunisia has produced more foreign fighters than any other country, there is no question that it has the highest proportion of such fighters as a share of population. By contrast, relatively few foreign fighters come from Algeria (see chart below).

During 2014, ISIS began to establish a presence in Libya. With its largest Libyan contingent based in Sirte, the group also established a camp at Sabratha, near the Tunisian border, that focused on training Tunisian fighters.[6] As many as 1,500 Tunisians may have trained or fought in Libya.[7] Among them were the men responsible for attacks in 2015 against two prominent tourist destinations: the Bardo Museum in Tunis (where 22 civilians were killed) and the beach resort of Sousse (where 38 civilians, including 30 British tourists, were killed). Tunisians who had joined ISIS in Libya led the armed attack on the Tunisian border town of Ben Guerdane in March 2016, which the Tunisian security forces defeated with the assistance of the local population. In 2016, Libyan forces backed by US airpower pushed ISIS out of the areas of Libya it controlled. Yet many ISIS fighters are believed to remain at large in the country.

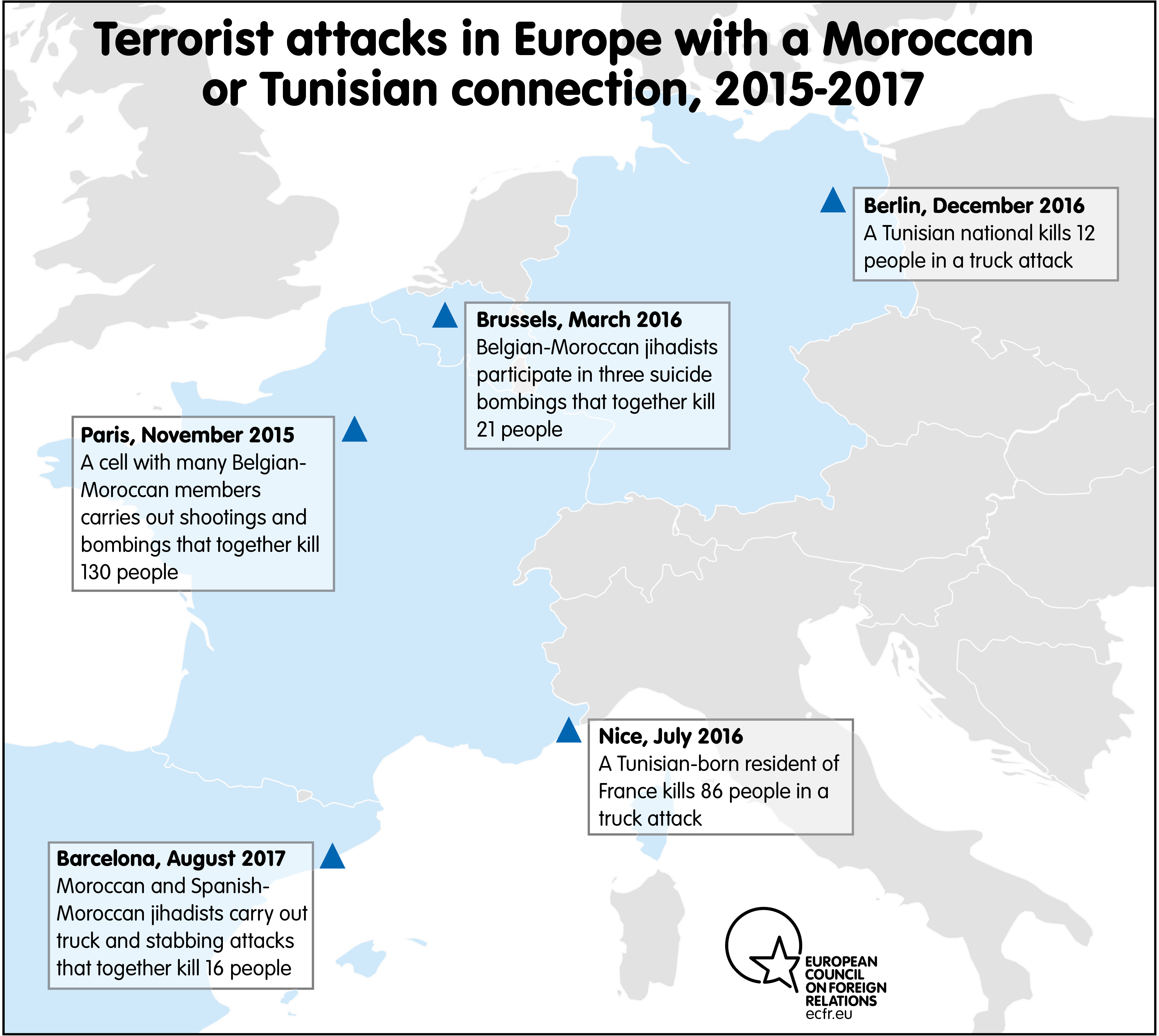

Militants with links to countries in the Maghreb have also been responsible for several attacks in Europe. Assaults in Paris in November 2015 and in Brussels in March 2016 involved a cell led by Belgians of Moroccan descent, while that in Barcelona in August 2017 involved a cell largely composed of Moroccan citizens – most of whom were the sons of immigrants.[8] A Tunisian-born resident of France carried out the truck attack in Nice in July 2016. In all these cases, the attackers appear to have been radicalised in Europe, and the plots developed in either Europe or Syria. Anis Amri, the Tunisian militant responsible for the 2016 Christmas market attack in Berlin, falls partly outside this pattern, as he seems to have developed his plans for the attack by communicating with Tunisian jihadists based in Libya.[9]Nevertheless, the risk of attacks by members of the Moroccan and Tunisian communities in Europe affects EU member states’ security relationships with Morocco and Tunisia.

Tunisia: reinforcing and reforming the security services

In 2015, it seemed that the security threats Tunisia faced might imperil its transition to democracy. The attacks against tourist targets in Tunis and Sousse not only endangered a vital source of national income but also revealed serious weaknesses in Tunisia’s security services, particularly their limited capacity and effectiveness, lack of coordination in responding to threats, and inability to prevent militants crossing into Tunisia from Libya. With substantial foreign support, the Tunisian authorities responded to this moment of crisis by launching a programme that restructured the security services and improved the country’s defences against terrorism. So far, the programme has focused on addressing the vulnerabilities that the attacks highlighted.

New structures and capacities

The security system Tunisia’s authorities inherited after the 2011 revolution centred on the police, internal security forces, and the intelligence services. It included only a limited role for the army due to the concerns of Tunisia’s post-independence authoritarian leaders, Habib Bourguiba and Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali. Both rulers worried about the possibility of a military coup, and about internal opposition and domestic Islamism rather external security threats.[10] The revolution left the security services in a difficult, ambiguous position, because the Tunisian public associated them with the former regime’s repressive political system.

This mistrust of the security services led to the formal abolition in February 2011 of the Directorate of State Security, the main arm of the former regime’s security apparatus. Although the internal structure of the Ministry of the Interior remained essentially unchanged following the revolution, some analysts argued that the removal of the Directorate of State Security weakened the coordination of security policy.[11] After a coalition led by the Islamist Ennahda party took power in late 2011, Ali Larayedh, who had spent 14 years as a political prisoner under Ben Ali, gained responsibility for overseeing the ministry. According to many accounts, these dramatic shifts and agents’ uncertainty about how to operate in the new, democratic environment led to poor morale in the security services.[12] As a consequence, these organisations were weak and disorganised at a time when security threats to Tunisia were growing.[13]

Since 2014, and particularly after the attacks the following year, there has been a far-reaching overhaul of the Tunisian security services’ structure and strategy. The government strengthened the army’s role in counter-terrorism, partly through the creation in 2015 of the Agency for Defence Intelligence and Security, which receives funding independent of the rest of the armed forces. In 2015, the government launched the National Commission on Counter-Terrorism, which joined the National Security Council in developing the new, comprehensive strategy on counter-terrorism and extremism unveiled in 2016.[14] Bearing a strong resemblance to European models, this strategy centres on the four pillars of prevention, protection, prosecution, and response to attacks. Finally, in early 2017, Tunisia set up the National Intelligence Centre, an institution designed to overcome problems with coordination and information-sharing between intelligence agencies that had plagued the country’s counter-terrorism efforts since the revolution.

Post-revolution governments have partially redressed the historical under-resourcing of the Tunisian army by investing in equipment suited to counter-insurgency campaigns, including helicopters and ambush-resistant armoured vehicles.[15] Army and police units’ effective response to the Ben Guerdane attack demonstrated an improvement in counter-insurgent capacity and, in turn, helped raise the morale of the security forces. Following the attack, the Tunisian authorities stepped up their investment in border security. This has focused on the construction of a 200km system of sand barriers and water trenches along the Libyan border, which has been supplemented with US-supplied surveillance drones and will eventually be equipped with electronic sensors.[16] Since 2013, Tunisia has also enforced a militarised buffer zone across Tunisia’s southern borders with Libya and Algeria, and has required prior authorisation for anyone seeking to enter the area. The government must renew the order to maintain the buffer zone annually, and most recently did so in August 2017.

European and other international support

Tunisia stands out among north African countries for its readiness to work with international partners on reforming and improving the capability of its security sector. The country accepted the need for a new approach following the 2015 attacks, by which stage it was already closely involved with international partners in several aspects of its transition to democracy, including security sector reform. European officials universally speak of Tunisia’s openness to cooperation in enhancing its security capabilities. While Tunisia’s requests tend to focus on equipment and training, the country has also embarked on a broader agenda of reform.[17]

International assistance to Tunisia has also been well coordinated. The main mechanism for coordinating security assistance is the G7+6 grouping, comprising the seven leading industrialised countries, as well as Spain, Belgium, the EU, Switzerland, Turkey, and the UN Office on Drugs and Crime. Each country or organisation takes the lead in providing a specific type of security assistance, a process designed to avoid duplication of effort and to ensure that all Tunisia’s major partners have a substantive role. According to EU officials, the G7+6 coalition helped prevent ISIS from seizing any Tunisian territory.[18]

With its historic ties to Tunisia, France has led direct work with the country’s security services, including by providing intelligence to, and equipping, Tunisian special forces. France and the United Kingdom have taken charge of working with Tunisia on aviation security, including by improving passenger screening. These countries have also helped train a cadre of Tunisian agents – who will in turn train other Tunisians – on the initial response to terrorist incidents. The UK has worked on hotel security (including that involving the use of quad bikes on beaches) and medical training for first responders.

Germany and the United States have taken the lead on border security. These countries are jointly funding the installation of the electronic surveillance system along Tunisia’s border with Libya, which the US Defense Threat Reduction Agency will manage. Germany has also provided mobile observation equipment. Italy has focused on the fight against human trafficking and its connection with counter-terrorism, including by supplying and maintaining patrol vessels, as well as other measures to strengthen maritime borders.[19] The areas EU member states have chosen to concentrate on reflect their national priorities and domestic political concerns.

EU Commissioner for Humanitarian Aid Kristalina Georgieva visits camp in Raz Ajdir, Tunisia (EHCO, http://bit.ly/2EIYAX9)(CC BY-ND 2.0)

Meanwhile, EU institutions have focused on security sector reform, including assistance in drawing up and implementing a programme to provide independent oversight of the police, and developing the investigative capacity of security services under the rule of law. Belgium, Norway, and Japan have supported a UN Development Programme pilot project to rebuild trust between the citizens and police through the development of community-focused police stations.[20] The EU, along with France, has supported the modernisation of Tunisia’s judiciary, improving its capacity to prosecute terrorism cases.[21]

Limitations of reform

European officials generally agree that Tunisia’s security services have considerably improved their capacity to prevent and respond to terrorist threats since 2015. The fact that there have been no significant terrorist attacks in Tunisia since the March 2016 assault on Ben Guerdane seems to reflect this improvement (although ISIS territorial losses in Libya likely also contributed to the trend). Nevertheless, the overhaul of Tunisia’s security and counter-terrorism strategy and structures has failed to resolve some problems and even created a few new difficulties.

The reform of the security services under the authority of the Ministry of the Interior has made little headway. As one European official put it, the Tunisian security services “have been pushed into the logic of reform, but it is hard to advance with this agenda”. Another European official observed that the director for international cooperation in the Ministry of the Interior remains the same person who held the post during the Ben Ali era: “He is undoubtedly efficient, but not clearly committed to reform”. These observations seem to confirm the precept that in transitions from authoritarian rule, institutions that were at the centre of the old regime’s repressive apparatus are the slowest to reform.[22]

The slow pace of reform has meant that silos within the ministry still tend to communicate poorly with one another – although there has been some progress in this area since 2015. More importantly, the ministry remains resistant to independent oversight. Researchers note that many members of the security forces associate the revolution and democratic transition with partisan power struggles rather than an opportunity to rebuild the social contract between Tunisia’s police and people.[23] As one European security expert noted, the rise of security threats in Tunisia in the last few years has made reform of the Ministry of the Interior more difficult, as many officials continue to believe that police transparency and accountability would be an impediment to fighting terrorism.[24]

During this period, human rights organisations have documented an increase in some of the repressive practices associated with the authoritarian era. Despite the improvement in the security situation, Tunisia remains under a state of emergency imposed in November 2015, with President Beji Caid Essebsi having extended it – for three months – most recently in November 2017. Using emergency powers, the security forces have carried out thousands of raids and house searches without judicial authorisation, and placed dozens of people under assigned residence orders. Amnesty International has reported that the use of torture and other ill-treatment is still widespread in Tunisian detention centres, especially those operated by the Ministry of the Interior’s terrorism investigation brigades.[25] In November 2017, Essebsi renewed his push to pass a law on the protection of the security forces, which critics believe could be used to criminalise criticism of these services or marginalise calls for them to be held accountable for human rights abuses.[26]

Some Tunisians fear that Essebsi may use the fight against terrorism to strengthen the powers of his office at the expense of the prime minister, Youssef Chahed. This concern stems from the announcement in 2017 that the National Security Council was establishing a series of standing committees to cover the security-related aspects of various government portfolios, including health, education, energy, and transport. The move raised the possibility that security would provide a pretext for the development of a parallel government centred on the presidency.[27]

Finally, there are reasons to fear that Tunisia is focusing on border security in a narrow and potentially counterproductive way. The government’s vision for security on the border with Libya centres on the prevention of all informal movement of people and goods between the two countries, a measure that could damage the informal trade (unrelated to terrorism) that is crucial to local economies.[28] The government’s public discourse sometimes seems to imply that smuggling, corruption, and the illicit movement of people and weapons across borders are all linked, but detailed case studies of border regions show that the dynamics are far more complex. The securitisation of the border appears to have increased corruption and led to greater inequality.[29] Without corresponding policies to increase investment in this deprived region and provide local residents with alternatives to traditional trade, the securitisation of the border risks further alienating many of the area’s residents from the state.

Unaddressed challenges

Beyond these shortfalls, Tunisian and international observers agree that Tunisia’s biggest challenge concerns the prevention of radicalisation and efforts to deal with radicalised individuals. The country’s lack of an integrated, cross-government strategy is particularly apparent in this area.

Tunisia appears to have no effective policy for handling the possible return of the many Tunisian citizens who left the country to join ISIS and other jihadist groups. According to official figures, at least 800 fighters have come back so far.[30] The president’s counter-terrorism adviser, Admiral Kamel Akrout, says that in each case Tunisia has put in place a “tailor-made approach”, involving rehabilitation, reintegration, travel restrictions, and deradicalisation in prison.[31] But European officials say that accurate information is difficult to obtain; some experts believe three times as many fighters may have returned, with many of them evading detection by the authorities.[32] In addition, the government must find a way to handle the people whom it has prevented from travelling to join jihadist groups. According to official statistics, there are 12,000 such people in Tunisia – although independent researchers estimate the true figure to be much lower.[33]

Tunisians who join jihadist groups can be prosecuted for “terrorist crimes” or put under administrative surveillance under the 2015 Law on Combating Terrorism and Money Laundering. But there is little evidence that the government has taken any systematic approach to deradicalisation. The Tunisian prison system is already severely overcrowded, with some jails operating at 150 percent of their capacity. Although a project on deradicalisation in prison was launched in late 2015, with support from the Netherlands, it is only a small step in addressing the problem.

Many countries, including EU member states, are struggling to deal with returning foreign fighters. However, the problem is especially acute for Tunisia due to the disproportionately large number of Tunisians who travelled abroad to join jihadist groups.

In addition, Tunisians have been responsible for some large-scale terrorist attacks in Europe. The Tunisian intelligence services lack their Moroccan counterparts’ detailed knowledge of expatriate communities; European intelligence services do not look to the Tunisian government for assistance in penetrating cells in Europe. In their dealings with Tunis, European governments focus on speeding up the return of Tunisian migrants whose asylum claims have been rejected.[34]Meanwhile, Tunisian security experts complain that European intelligence services do not provide them with sufficient information on Tunisian nationals who are on European watch lists.

Large-scale radicalisation in Tunisia derives from the repressive policies of the Ben Ali era – which drove all expressions of political Islam underground and thereby encouraged the growth of extremism – and the rapid removal of state controls on society from 2011 onwards. In the aftermath of the revolution, the authorities indiscriminately released jihadists (along with political prisoners) from jail, many radical preachers took control of mosques, and the abolition of restrictions on the internet allowed for widespread access to extremist websites.[35] According to independent researchers, as many as 500 mosques fell under the leadership of Salafis – although that number is significantly lower according to official figures.[36] Successive governments have made efforts to regain control of the religious sphere a priority in the fight against radicalisation, progressively shutting down mosques in which the state lacks influence.[37]

However, state control of the religious establishment operates in the context of Tunisia’s democratic political system, with the Ennahda party a moderate Islamist force. In these conditions, finding a balance between preventing extremist messaging and avoiding the politicisation of Islam is more difficult than in Morocco, where the king remains above politics as the commander of the faithful. Tunisia still needs to chart a path between anarchy and heavy-handed state control in religious matters. Moreover, the religious establishment remains poorly trained, hindering imams’ ability to provide convincing anti-extremist discourse. According to Tunisian practitioners of Islamic studies, only around 7 percent of Tunisian imams have received a religious education, while just 30 percent hold a university degree.[38]

However, the persistent economic, social, and political marginalisation of significant parts of the country’s population is the most important obstacle to efforts to fight radicalisation in Tunisia. Akrout lists feelings of frustration, injustice, and failure, along with social stigmatisation and a lack of economic opportunities, as being among the main drivers of youth radicalisation.[39] Although individuals react to such circumstances in different ways, research in Tunisia has shown that a disproportionately high number of Tunisians who join terrorist groups come from deprived regions such as Sidi Bouzid, Kasserine, and Medenine – and that a sense of thwarted aspirations is particularly common among radicalised individuals.[40] The continuing feeling of economic and social disadvantage in Tunisia has repeatedly given rise to waves of protest, most recently against price rises associated with economic reforms. In this sense, the government could make the most significant improvements to security by fulfilling the promise of the revolution: treating Tunisians with greater respect, and providing them with substantive economic and social opportunities.

Morocco: capabilities and deficiencies of a strong state

Morocco’s official discourse presents the fight against terrorism as centring on a global, multidimensional strategy spearheaded by strong, coordinated institutions and overseen by the nearly omnipotent figure of King Mohammed VI. Morocco, which used the Arab uprisings as an opportunity to revamp its international image, is increasingly accepted as a model of political stability, economic development, and regional integration in Africa and the Middle East. A central element in this carefully cultivated picture is Morocco’s apparent success in avoiding the wave of terrorism that has afflicted its neighbours, and the role it has assumed as one of Europe’s key security partners in the region. However, Morocco’s approach to counter-terrorism is inseparable from the state’s tight control over its domestic population and its undemocratic and unaccountable political system.

Morocco has benefited from substantial European capacity-building assistance in operations and training, as well as from development funds and initiatives designed to assist the population and, by extension, curb the drivers of extremism. While it has long had particularly close relationships with France and Spain, the Moroccan monarchy has been significantly increasing its level of cooperation with non-traditional European allies such as Germany and the UK. Since April 2016, Morocco has co-chaired the Global Counterterrorism Forum with the Netherlands, and was re-elected for a second term in November 2017.

The Moroccan regime bases its claim to have developed a distinctive, effective approach to counter-terrorism on the lack of attacks in Morocco since 2011 and the number of plots it has thwarted. The media-friendly director of the country’s Central Bureau of Judicial Investigation (BCIJ), Abdelhak Khiame, told the press in October 2017 that Morocco had pre-empted 352 attacks and successfully dismantled 174 terrorist cells since 2002.[41]The BCIJ claims to have dismantled 44 ISIS-linked cells since its creation in 2015.[42]

European officials note that the Moroccan definition of a cell appears to be rather loose: there is little clarity about the degree of organisation needed to constitute a cell, or the activities that lead to charges of planning an attack. According to European diplomats, the Moroccan authorities break up suspected cells at the earliest possible stage – even before members of the cell have developed any meaningful plan of action. Nevertheless, European officials also acknowledge the Moroccan state’s effectiveness in controlling its territory.

The Moroccan surveillance state

Both domestically and abroad, Morocco has a proven track record of expertise in human and signals intelligence. Morocco operates as a tight and effective security state, working through an extensive network of security officials and informants that blankets the nation. The authorities’ advanced territorial mapping of the whole country has been particularly successful in detecting changes in citizens’ habits that may signal their radicalisation.

Around 50,000 mqadmin (auxiliary agents) mandated by the Ministry of Interior are present across all the nation’s urban and rural neighbourhoods, and act as informants who report back on any unusual behaviour by local residents. Nicknamed “the eyes and ears of the state” by the citizenry, the mqadmin have become a crucial element in Morocco’s security apparatus. Yet, the mqadmin’s role and duties are not clearly defined in law. They have an ambiguous status as both official and temporary public servants, a situation that is convenient for the authorities, which avoid accountability by keeping the mqadmin’s role and potential role unregulated. The mqadminhave a reputation for involvement in corruption and human rights abuses. But, as pillars of the state’s intelligence network, they have since 2011 received significant salary increases, as well as official recognition of their work.

European officials have admitted that a number of attacks in Europe might have been prevented had domestic intelligence services been allowed to employ the kind of human intelligence network established in Morocco. Information the Moroccan intelligence services drew from their extensive network of informants among the Moroccan diaspora in Europe was essential to finding the ringleader of the November 2015 attacks in Paris.[43]Operatives from Morocco’s foreign intelligence agency have worked in Europe for several decades through the nation’s consulates. But the prominent role played by members of the Moroccan diaspora in recent attacks in Europe has led to an expansion of Morocco’s counter-terrorism efforts on the continent. Following the Barcelona attacks in 2017, Khiame announced that the BCIJ’s mission would be expanded to surveillance of the Moroccan diaspora in Europe.[44]

Morocco is also expanding its work in signals intelligence with the assistance of its European partners, primarily France, the UK, and Germany. The Moroccan authorities use a variety of pre-emptive digital surveillance techniques to identify and prosecute suspects, such as monitoring phone calls involving individuals on watch lists, and registering suspicious internet searches. In all, the Moroccan authorities are believed to use 19 human and digital platforms to monitor the population, including on the dark web.

According to Moroccan security practitioners, however, the country still lacks expertise in cyber security, an area that the Royal Moroccan Armed Forces oversees.[45]Created in 2011, the General Directorate of Information Systems was initially tasked with responding to emerging cyber threats, but its mission quickly evolved to include “securing and controlling” cyber traffic and web activities.[46] Morocco’s cyber security could be strengthened through the creation of a more centralised system for accessing information and by improved data sharing between agencies and institutions.

In November 2017, Morocco became the first north African country to launch a high-resolution surveillance satellite into orbit. Named after King Mohammed VI and built secretly in France, the satellite’s specifications and full range of capabilities are not publicly known. However, the system is believed to be capable of providing 24-hour monitoring and snapshots of any location in the world.[47]

While it has many potential uses, the satellite seems likely to be primarily used to monitor activity near Morocco’s border with Algeria. Such activity could include a military build-up, Algerian operations in support of the Polisario Front in Western Sahara, and the movement of migrants northwards into Morocco on their way to Europe. Given the ongoing protests in Morocco, it is possible that the satellite will also be used to monitor Moroccan citizens.

The growing threat of terrorism across north Africa – particularly that from foreign fighters returning from conflicts in Syria and Iraq – led the Moroccan state to launch a new counter-terrorist operation in 2014. Named Operation Hadar, the mission involved the deployment of a range of military units and security forces around the country, beginning with the urban centres of Casablanca, Rabat, Marrakech, Fez, Tangier, and Agadir. Having secured these cities, the authorities extended the operation to other regions, including rural areas. The operation was designed to protect Morocco from terrorist infiltration using patrols of airports, train stations, and other transport hubs, as well enhanced border monitoring.

Reportedly involving patrols by security personnel armed with automatic weapons in residential neighbourhoods in Casablanca, Hadar demonstrated Morocco’s security-first approach to counter-terrorism. The country’s international partners have welcomed the operation, but it has not been universally popular at home. Some Moroccans worry that the regime’s hard-line approach will lead to the creation of a police state more focused on widespread surveillance of the population than on protecting those at risk.

Soft power and the religious sphere

An important element of Morocco’s security strategy is state control of the religious sphere. As commander of the faithful, the king retains overall religious authority in the country, enabling the central government to not only retain a measure of religious legitimacy but also to dictate which religious practices and interpretations are deemed acceptable – including those among the religious establishment.

Arguably, Morocco has been far more successful at asserting control over religious life than other states in the Middle East and north Africa, which have attempted to either coerce religious figures into complying with their dictates using threats and authoritarian legal measures, or else tried to co-opt them. Saudi Arabia has until recently taken the latter approach, maintaining the royal family’s religious legitimacy by catering to the country’s ultraconservative clerical establishment. In contrast, the Moroccan monarchy has effectively maintained the king’s authoritative and determinative role as head of the religious establishment.

Morocco has made a substantive attempt to counter radicalisation in implementing an imam training programme, a large-scale initiative involving clerics from Morocco, other African countries, and Europe that aims to curtail the proliferation of extremist thought among the religious establishment and the wider population. So far, more than 900 imams and women preachers from across Africa and Europe have graduated from the Mohammed VI Institute for the Training of Imams, Morchidines, and Morchidates.[48]Morocco launched the institute, along with the Mohammed VI Foundation for African Ulema, in 2015.

An important facet of Morocco’s soft power and foreign policy efforts, these programmes constitute a pillar of the country’s broader African integration strategy. Due to the imam training programme’s success and positive public image, Morocco is now seeking to establish similar partnerships with Italy, Spain, Belgium, the Netherlands, and other European states. Moreover, Morocco has established a religious council for the Moroccan diaspora in Europe, aiming to assist host countries with religious education. Together with intelligence cooperation, Morocco’s religious training initiatives appear to be a form of security diplomacy designed to improve the country’s reach and international standing.

At home, Morocco has adopted a strategy of systematic control of religious guidance and activities, attempting to introduce state-sponsored mechanisms into all religious spaces. The state’s religious messaging takes the form of religious programmes on national television and radio stations, control of school curricula, and a ban on proselytising. However, despite the state’s effective monopoly on the religious sphere, it is difficult to determine whether this messaging has an impact on disenfranchised young Moroccans, many of whom have little trust in the state and its institutions.

Moroccan imam in Fez (Luigi Torreggiani http://bit.ly/2EqKme7), (CC BY-ND 2.0)

Indeed, counter-radicalisation remains Morocco’s weak point. The fact that the security services have thwarted a high number of terrorist plots reflects their capacity to detect and prevent attacks, but it also indicates the extent to which many young men and women remain susceptible to extremist messaging. In an all too familiar pattern repeated across the world, the government points to the tactical successes of its counter-terrorism operations while downplaying the underlying conditions that necessitate these operations.

The number of Moroccans who have joined foreign-based terrorist groups also testifies to the continuing appeal of jihadist ideology among the population. Among the more than 1,600 Moroccans who have fought with jihadist groups in Syria and Iraq, only a small number are thought to have returned home. While the number of fighters who have been killed remains unclear, many may attempt to join jihadist groups elsewhere as the ISIS “caliphate” crumbles. In this, Morocco appears to have exported its terrorism problem to some extent. While the country’s extradition activities and cooperation with EU nations remains strong, north African and Arab states are hardly eager to see foreign fighters return home from the lawlessness and chaos of war-torn Syria and Iraq – defeated, embittered, and far more isolated and disenfranchised than when they left, but equipped with deadly new skills and connections to networks of extremists elsewhere.

Some civil society groups appear to be making promising efforts to counter radicalisation – but, overall, the strong grip of the Moroccan security state leaves little room for the development of effective multidimensional approaches to counter-terrorism. A disproportionately high number of Moroccans who have joined extremist groups come from cities with large poor neighbourhoods, such as Fez, Casablanca, Salé, and Marrakech, as well as the marginalised areas of Rif and other parts of the north.[49] The state’s repression of communities there appears to be counter-productive, leaving individuals alienated and resistant to the regime’s messaging. The poor conditions, corruption, and violence evident in Morocco’s overcrowded prison system create a favourable environment for those seeking to recruit inmates to extremist groups.

However, the Moroccan state has engaged in some positive efforts to counter radicalisation. Although the state is generally resistant to reform, it has approached international organisations to work with it on combating corruption within the police and improving treatment of prisoners, including by training medical personnel to identify signs of abuse.[50] Locally, the UN Development Programme, in partnership with the Japanese government and the General Commission for the Management of Prisons and Reintegration, has led a large-scale project to modernise the Moroccan prison system. Moreover, Morocco has announced that it will create 36 new prisons by 2020.[51]

Morocco-EU relations

Bilateral security cooperation is central to Morocco’s relationships with European countries. European diplomats in Rabat say that through efforts to nurture close personal relationships, services and officials on both sides have developed trust and confidence between institutions, leading to stronger cooperation. Security cooperation between Moroccan agencies and their European counterparts appears to effective, with the sides regularly exchanging information and best practice.

Morocco has established productive partnerships with many EU member states. In recent years, Germany and the UK have made particular effort to reinforce their security cooperation with the country. Nevertheless, Morocco’s relationships with Spain and France stand out. Both Madrid and Paris have for many years benefited from a significant level of mutual trust with Rabat, enabling them to work together on both training and operations. This security cooperation has served as a reliable bedrock in the countries’ wider bilateral relationships, even during periods of political and diplomatic tension.

The Moroccan and Spanish security services have developed a deep knowledge of criminal and extremist groups operating throughout the region, and have established effective extradition mechanisms. On the ground, Morocco and Spain have participated in joint operations to prevent extremist violence and arrest those responsible for attacks, particularly since 2013.

Morocco and Spain regularly exchange intelligence through coordinators, with agents co-located in both countries. In many cases, intelligence officers prefer to bypass officialdom and bureaucracy by using unofficial channels, as the two nations enjoy a fairly direct relationship in their work to deal with organised crime, trafficking, and smuggling, as well as other transnational issues of mutual concern.[52]

In many cases, Moroccan intelligence agencies now operate to the same standard as their European counterparts, partly due to cooperation that has enabled each side to develop skills, adopt new techniques and methods, and make use of the other’s resources. Nevertheless, financial or capacity issues sometimes limit this cooperation: many of Belgium’s security cooperation programmes with Morocco have been suspended due to Belgian resource constraints – despite the importance of the Morocco-Belgium relationship and the large Moroccan community in Belgium.[53]

Moroccan counter-terrorism cooperation with both European countries and the US is not only a security endeavour but also a crucial component of Rabat’s long-term efforts to strengthen economic and political ties with these countries. Morocco aims to minimise international outcry over the Western Sahara issue, encourage greater foreign investment and tourism, maintain access to Western military equipment and training, and promote Morocco’s integration into NATO’s strategic plans.

Having positioned itself as a capable security actor, Morocco has become – in contrast to Tunisia – resistant to any suggestion that it could benefit from external advice on its counter-terrorism strategy. International cooperation takes place on Morocco’s terms. This is due to its apparent success in enforcing domestic security and Europeans’ perceptions of its value as a security partner. Although Morocco has strong security relationships with some EU member states, others find it a difficult and inflexible partner because of its resistance to reform. Morocco’s security relationships with EU institutions have been complicated by the EU’s promotion of a security strategy based on human rights, as well as the European Court of Justice’s December 2016 ruling against the country’s claim to Western Sahara.

Morocco’s developmental shortfalls

Rabat’s approach to security creates an incentive for its international partners to overlook the domestic repression that may contribute to radicalisation in Morocco, lest they disrupt the flow of intelligence to them from Moroccan agencies. Nevertheless, the country’s counter-terrorism strategy cannot be considered in isolation from broader developmental and governance questions. Morocco’s levels of development do not match its international position as an advanced security state. Morocco has the highest level of inequality of any country in north Africa, one-third of its adult population is illiterate, and 29 percent of young Moroccans are unemployed.[54] The state is doing little to address these issues, despite the concentration of radicalised individuals in economically deprived urban areas. Protests that began in the marginalised Rif region last year have persisted and expanded beyond Rif, despite the state’s imposition of heavy prison sentences on many demonstrators, journalists, and lawyers.

The Moroccan government regularly uses security issues to justify restrictions on civil liberties. In 2015, Morocco announced a project to reform its penal code.[55] The country framed the discourse around these reforms in liberal terms, lauding the modernisation of the system as a boon to the nation’s flourishing civil society and as a vehicle to enhance public freedoms. Yet, to date, the only “reforms” have been the introduction of longer prison sentences for public protest and online activities, and narrowing civic and political freedoms. Since promising reform following the onset of the Arab uprisings, Morocco has markedly increased restrictions on activists’ and researchers’ freedom of speech. The efforts made by the Association Marocaine des Droits Humains and other local grassroots civil society and human rights groups to secure greater democratic freedoms have met with increased state violence and harassment.

Morocco’s counter-terrorism strategy appears to be inseparable from its authoritarian political system. The state’s far-reaching surveillance of its population and the king’s role as the personification of religious authority may contribute to Morocco’s image as a bastion of security, but they are also bound up with its resistance to genuine political accountability – with the all the limitations this involves.

Conclusion

Viewed superficially, Morocco might seem to be a capable security partner for the EU in north Africa, and Tunisia a potential weak link. Yet the reality is more complex. Morocco has been successful in preventing attacks and obtaining information that can benefit its European partners, but its counter-terrorism efforts fit within a framework of conserving rather than transforming the state’s unaccountable relationship with its subjects. This has acted as a constraint on tackling social, economic, and governance problems that appear to help extremist groups recruit followers.

Tunisia continues to struggle with the legacy of authoritarian rule and the convulsions of the post-revolutionary period. The country has made significant advances in its security policies but has yet to find balanced ways to deal with its porous borders and the disproportionately large number of radicalised Tunisians. Tunis formulates security policy against a background of complex and incomplete political transition, in which a constitution based on the principle of accountability coexists with a security sector that is in many areas reforming slowly, if at all. This creates complications for European partners, but also offers an opening to pursue broader questions of security sector reform and accountability that most European policymakers would regard as essential to an effective counter-terrorism strategy.

The EU has worked closely with both Tunisia and Morocco to combat the threat of jihadist terrorism within their territory and in Europe. This cooperation has been effective in different ways in both countries, but more can be done – especially in relation to improving the culture and professionalism of the security forces. In Tunisia, international partners should follow through on existing reform programmes, encouraging further openness within the Ministry of the Interior to help the institution improve its cooperation with the country’s citizens. Greater professionalism within the security services would make it easier for European partners to share intelligence with Tunisia. European countries and the EU should also encourage and support Tunisia in developing programmes to promote religious education and awareness, gearing them towards pupils and their families from an early age.

In Morocco, European countries, particularly France and Spain, should encourage and support measures to combat corruption and abusive practices within the security services. While Morocco is unlikely to establish a culture of genuine public accountability any time soon, European partners can argue that greater professionalism is in the interests of Moroccan authorities, as it will ensure that their attention is focused on real threats while reducing public alienation from the state.

The most significant remaining challenges in both countries relate to the treatment of radicalised individuals and the prevention of further radicalisation. As these are complex problems that affect European and north African countries alike, Europeans should avoid suggesting that they have all the answers. Nevertheless, European countries could work with Tunisia and Morocco to explore better ways to handle radicalised individuals than large-scale incarceration, and to distinguish between committed jihadists and those who are more open to reintegration into society.

Beyond this, there is convincing evidence that, in north Africa, frustrations with a lack of economic opportunities and social justice increase the likelihood that people will join jihadist groups. It is undoubtedly easier for European countries and their north African partners to implement direct security measures than to make progress on the complex social, economic, and governance questions that lie behind marginalisation and regional inequality. But if these security measures distract from the need to pursue solutions to these broader concerns, the response to security problems in Tunisia and Morocco will remain incomplete. The EU should make sure that it remains committed to encouraging and supporting the reform of state structures in Tunisia and Morocco, as well as working to reduce the socioeconomic disparities and lack of opportunities that remain the public’s most pressing problems in both countries.

About the authors

Anthony Dworkin is a senior policy fellow at ECFR, working on north Africa, counter-terrorism, and human rights. Among his recent ECFR publications are “Europe’s new counter-terror wars” (2016) and “Egypt on the edge: How Europe can avoid another crisis in Egypt” (with Yasser el-Shimy, 2017). He is also a visiting lecturer at the Paris School of International Affairs at Sciences Po and was formerly the executive director of the Crimes of War Project.

Fatim-Zohra El Malki is a doctoral researcher at the University of Oxford and a visiting fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations. She was previously a researcher on Islam and politics at the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East in Washington, DC. Fatim-Zohra’s research focuses on counter-terrorism, law, and institution-making in the Maghreb region.

Acknowledgements

This policy brief draws on interviews with European officials and North African security experts in Europe, Morocco, and Tunisia. The authors are grateful to all those who spoke with them, mostly on a non-attributable basis. Within ECFR they would like to thank Ruth Citrin, Adam Harrison, Jeremy Shapiro, and Chloe Teevan for their comments on drafts of the paper, and Chris Raggett for editing and creating the graphics. ECFR would like to thank Compagnia di San Paolo for its support in producing this publication, and the foreign ministries of Norway and Sweden for their support for the ECFR Middle East and North Africa Programme.

[1] Alison Pargeter, “Radicalisation in Tunisia”, in George Joffé (ed.), Islamist Radicalisation in North Africa: Politics and Process (London: Routledge, 2011), p. 82.

[2] Rogelio Alonso and Marcos García Rey, “The Evolution of Jihadist Terrorism in Morocco”, Terrorism and Political Violence, October 2007, p. 584.

[3] Jean-Pierre Filiu, “Al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb and the Dilemmas of Jihadi Loyalty”, Perspectives on Terrorism, December 2017, p. 169, available at http://www.terrorismanalysts.com/pt/index.php/pot/article/view/665/html.

[5] All figures on foreign fighters in this paragraph are taken from Richard Barrett, “Beyond the Caliphate: Foreign Fighters and the Threat of Returnees”, Soufan Centre, October 2017, pp. 12-13, available at http://thesoufancenter.org/research/beyond-caliphate/ (hereafter, Barrett, “Beyond the Caliphate”).

[7] Zelin, “The Others”, p. 3.

[10] Michael Willis, Politics and Power in the Maghreb (London: Hurst, 2012), pp. 86-88, 103-105.

[12] Flavien Bourrat, “Le rensignement tunisien: Comment passer d’un État policier à un État de droit?”, Moyen-Orient, October-December 2017, p. 57 (hereafter, Bourrat, “Le rensignement tunisien”); “Reform and Security Strategy in Tunisia”, Crisis Group, July 2015, p. 8, available at https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/north-africa/tunisia/reform-and-security-strategy-tunisia (hereafter, “Reform and Security Strategy”).

[13] Bourrat, “Le rensignement tunisien”, p. 56.

[17] Here and throughout this brief, all direct quotations are taken from ECFR interviews with European officials in Europe, Morocco, and Tunisia conducted between July and December 2017, except where otherwise indicated.

[18] ECFR interview with EU officials, Tunis, August 2017.

[22] ECFR interview with European security expert, 19 January 2018.

[23] “Reform and Security Strategy”, p. 12.

[24] ECFR interview with European security expert, 19 January 2018.

[28] Hamza Meddeb, “Precarious Resilience: Tunisia’s Libya Predicament”, MENARA, April 2017; Anouar Boukhars, “The Geographic Trajectory of Conflict and Militancy in Tunisia”.

[36] ECFR interview with researchers at the Centre for the Study of Islam and Democracy (CSID), Tunis, 10 August 2017.

[38] ECFR interview with CSID researchers, 10 August 2017.

[39] Akrout, CSIS presentation.

[43] Interview with French officials, July 2017.

[45] ECFR interview with a Moroccan security researcher, July 2017.

[52] ECFR interviews with Spanish officials in Madrid and Rabat, April-July 2017.

[53] ECFR interview with Belgian official, Tunis, August 2017.