Associated Press

BY Andrew Drake

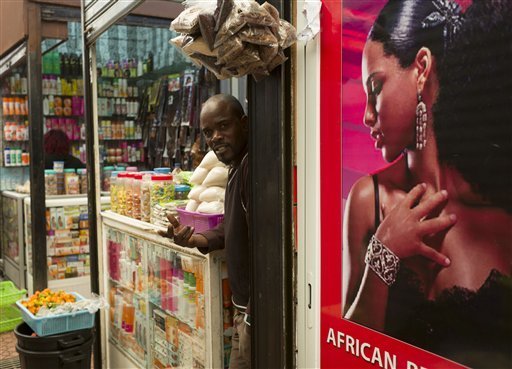

Marthe N’Dri began her beauty business in Morocco by going to people’s homes to do braids and hair weaves, using skills she picked up as a beautician in her native Ivory Coast.

Now she’s ready to expand her tiny corner stall in the narrow warren of alleys known as the Senegalese Market in Casablanca. She plans to install a chair next to the racks of hair extensions, cosmetics, plantains and bags of manioc, and make her fellow migrants beautiful – with the help of local organization providing funds and business advice to newcomers.

It is simple dreams like this that could be the future face of immigration in Morocco. African migrants who originally planned to make the perilous crossing from Morocco to Europe are increasingly deciding instead to set up shop in the North African kingdom, taking advantage of new laws that make it easier for the migrants to obtain permanent residency and work permits here.

“I need a bit of help to grow my business so that I can move forward,” said N’dri, thanking the organization that gave her the money to start her shop. “There was no one else.”

Over the past year, Morocco has been working to grant legal status to the tens of thousands of immigrants who arrive with European dreams to give them an opportunity to settle and take advantage of the health and education system. Already 27,000 migrants living in Morocco have applied for papers and 18,000 – including all of the women and children who applied – have received residency.

One new addition to the program, announced last month, is to help the immigrants start small businesses. For now, the business program is restricted to registered refugees and funded by the U.N. But soon it will be expanded with funding from the European Union to all migrants in Morocco with legal status. Morocco has been under pressure from its European neighbors to stem the flow of migrants using the country as a transit point, and that pressure has been a catalyst for the new immigration policy.

If the laws are now favorable for migrants in Morocco, they are also getting a boost from organizations teaching the newcomers how to make it in an unfamiliar land. N’Dri is being advised by the Moroccan Association to Support and Promote Small Businesses, known by the French acronym, AMAPPE, which helped set up her business and is now overseeing her plan to expand it.

The fact that N’Dri, who came as an illegal immigrant four years ago, is able to get such advice is a mark of how much Morocco has changed in its attitudes toward immigration.

“Moroccan society is in the process of changing, is becoming aware that there are foreign migrants, that they need to work, that they need to live with dignity, that they need the same rights to work, to housing, to health care as Moroccans,” said the director of AMAPPE, Said Makhon. The organization has so far given business support to 300 people and trained another 90.

Caseworkers at AMAPPE will review migrants’ business plans and then decide how best the organization can help them out with small grants.

The immigrants who decide to stay, however, face challenges making it in a poor country with 10 percent unemployment and a low growth rate. Many complain about racism. And in cities like Tangiers there have been frequent clashes between poor Moroccan youths and immigrants. Entrepreneurs like N’Dri often target their businesses at fellow migrants.

But in the capital Rabat, Fabien Manzingo, from the country once known as Zaire, is aiming his latest business venture squarely at a Moroccan clientele in the working class neighborhood of Taqadoum.

Unlike the others, Manzingo came here for work. He was the bodyguard for ousted dictator Mobutu Sese Seko, who took refuge in Morocco after being kicked out in 1997 by Laurent Kabila; the new leader renamed the country the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Following Mobutu’s death, Manzingo worked a string of jobs. His latest effort, thanks to start-up funding from AMAPPE, is Cafe Ouarzazate, cooking popular Moroccan lunch and breakfast dishes.

He has hired a cook and bought basic equipment, and now it’s just a matter of becoming a neighborhood fixture.

“It’s very, very difficult, but we have to, there is no other way to do anything else,” he said. “We have a saying among ourselves, life is a battle.”

—

Paul Schemm contributed from Rabat.