The Economist

BEIDA, MISRATA AND TRIPOLI

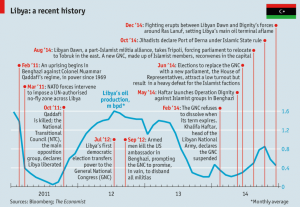

IN MARCH 2011, spurred by Colonel Muammar Qaddafi’s threat that his forces would storm the city of Benghazi “inch by inch, house by house, home by home, alley by alley,” reluctant Western nations intervened in the revolution in Libya. It proved decisive. By the end of the year Qaddafi was dead, and the national tricolour which had replaced the plain green flag of the colonel’s regime over the rooftops of Benghazi was flying all across the country.

Today Libya is at war with itself again. It is split between a government in Beida, in the east of the country, which is aligned with the military, another in Tripoli, in the west, which is dominated by Islamists, and a range of smaller forces in shifting alliances in between. Benghazi is again a battlefield. Parts of its university, where many government ministers on both sides of the new civil war used to teach, have been put to the torch. Across the country people shiver in the cold of freak snowstorms, many without running water or electricity. The black plumes of burning oil terminals stretch out over the Mediterranean.

How did it all go so wrong? When protests began in Benghazi in February 2011, fast on the heels of the downfalls of Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali in Tunisia and Hosni Mubarak in Egypt, Libya looked like the latest fragile blossoming of the Arab spring. Army commanders, mostly of Arab Bedouin origin, refused orders to shoot the protesters. The tents of hitherto-banned political movements, associations and newspapers crowded on to Benghazi’s seafront. With remarkable speed, the revolutionaries cobbled together a National Transitional Council (NTC) claiming to represent all of Libya.

Gossamer government

After French aircraft saw off Qaddafi’s attempt to retake Benghazi in March, Western and Gulf governments sent military advisers to extend the revolution towards the west. Volunteers from students to bank managers took up arms, joining popular militias and only sometimes obeying the orders of defecting army commanders trying to take control. In August Western bombing of government bases surrounding Tripoli cleared an avenue for the revolutionaries to take the capital. In October, after a fierce last stand in his hometown of Sirte, the colonel met his end.

Recognised abroad, popular at home and enjoying the benefits of healthy oil revenues—97% of the government’s income — the NTC was well placed to lay the foundations for a new Libya. But the judges, academics and lawyers who filled its ranks worried about their own legitimacy and feared confrontation with the militias which, in toppling Qaddafi, had taken his arsenals for their own. By the time the NTC’s chairman, Mustafa Abdel Jalil, arrived in Tripoli, militia leaders were already ensconced in the capital’s prime properties.

The NTC presided over Libya’s first democratic elections in July 2012, and the smooth subsequent handover of power to the General National Congress (GNC) revived popular support for the revolution. But Islamist parties won only 19 of 80 seats assigned to parties in the new legislature, and the process left the militias on the outside. The Homeland party, founded by Abdel Hakim Belhadj, a veteran of the Afghan jihad and prominent rebel emir who ran Tripoli’s military council, tried to advertise its moderation by putting an unveiled woman at the head of its party list in Benghazi: even so it won no seats.

Hopes that an elected government might use its political capital to rein in the militiamen were quickly dashed. The new prime minister, Abdurrahim al-Keib, a university professor who had spent decades in exile, fretted and dithered. He bowed to militia demands for their leaders to be appointed to senior ministries, and failed to revive public-works programmes, in full swing before the revolution, which might have given militiamen jobs. Many received handouts without being required to hand in weapons or disband, an incentive which served to swell their ranks; when the colonel was killed the number of revolutionaries registered with the Warriors Affairs Commission set up by the NTC was about 60,000; a year later there were over 200,000. Of some 500 registered militias, almost half came from one city, Misrata.

When Mr Keib or the elected parliament balked, the militias simply raided their premises. “The war wounded closed a parliament session for six weeks until we passed a law rewarding them,” recalls Mustafa Abushagur, then Mr Keib’s deputy. In May 2013 the militias forced parliament to pass a law barring from office anyone who had held a senior position in Qaddafi’s regime after laying siege to government ministries. That October militiamen briefly kidnapped Mr Keib’s successor as prime minister, Ali Zeidan.

With central government so weak, warlords revived latent tribal, regional and ethnic differences. Libya was created in 1963 from Cyrenaica in the east, Fezzan in the south and Tripolitania in the west, and the divisions still matter. The 2011 revolution started in Benghazi in part because the marginalised Cyrenaicans harked back to the time when their king split his time between the courts of Tobruk and Beida and when Arabs from the Bedouin tribes of the Green Mountains ran his army. Tensions between those tribes and Islamist militias ran high from the start. In July 2011 jihadists keen to settle scores with officers who had crushed their revolt in the late 1990s killed the NTC’s commander-in-chief, Abdel Fattah Younis, who came from a powerful Arab tribe in the Green Mountains. In June 2013 the Transitional Council of Barqa (the Arab name for Cyrenaica), a body primarily comprised of Arab tribes, declared the east a separate federal region, and soon after allied tribal militias around the Gulf of Sirte took control of the oilfields.

In the west, indigenous Berbers, who make up about a tenth of the population, formed a council of their own and called on larger Berber communities in the Maghreb and Europe for support. Port cities started to claim self-government and set up their own border controls.

As well as being split by sub-national loyalties, Libya is also pulled between supranational ones. From the very beginning of the revolution, Derna—a small port in the east famed for having sent more jihadists per person to fight in Iraq than anywhere else in the world—would have nothing to do with any attempts at imposing a central command on rebel forces. It opposed NATO intervention and insisted that the NTC was a pagan (wadani) not national (watani) council. Some in Derna have now declared their allegiance to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the caliph of the so-called Islamic State (IS) in Syria and Iraq. In December the head of America’s Africa command told reporters that IS was training some 200 fighters in the town.

A tale of two everythings

In the spring of 2014, Khalifa Haftar, a retired general returned from two decades of exile in America, forcibly tried to dissolve the GNC and re-establish himself as the armed forces’ commander-in-chief in an operation he called Dignity. The elections which followed were a far cry from the happy experience of 2012. In some parts of the country it was too dangerous to go out and vote; in the rest most chose not to anyway, seeing a process now dominated by bullets, not ballots. Such retrenchment has been particularly noticeable among women. In 2011 they created a flurry of new civil associations; now many are back indoors.

Turnout in the June 2014 elections was 18%, down from 60% in 2012, and the Islamists fared even worse than before. Dismissing the results, an alliance of Islamist, Misratan and Berber militias called Libya Dawn launched a six-week assault on Tripoli. The newly elected parliament decamped to Tobruk, some 1,300km east. Militias backing the parliament, including those from the Arab town of Zintan, fled to the Nafusa Mountains south-west of the city. Grasping for a figleaf of legitimacy, Libya Dawn reconstituted the pre-election GNC and appointed a new government.

So today Libya is split between two parliaments—both boycotted by their own oppositions and inquorate—two governments, and two central-bank governors. The army—which has two chiefs of staff—is largely split along ethnic lines, with Arab soldiers in Arab tribes rallying around Dignity and the far fewer Misratan and Berber ones around Libya Dawn. Libya Dawn controls the bulk of the territory and probably has more fighters at its disposal. But General Haftar’s Dignity, which has based its government in Beida, has air power and, probably, better weaponry.

Each side uses broadcast media to rally support. Heavily backed by Egypt’s general-turned-president, Abdel Fattah al-Sisi (an alliance that could seem like a poor prognosis for its more liberal supporters), the Dignity movement proclaims itself America’s natural ally in the war on terror and the scourge of jihadist Islam. Libya Dawn’s commanders present themselves as standard-bearers of the revolution against Qaddafi now continuing the struggle against his former officers. “We didn’t have a revolution to give rise to another military dictator,” says Brahim Masbah, a legislator elected in June 2014 who opposed parliament’s flight to Tobruk.

Ministers in the east vow to liberate Tripoli from its “occupation” by Islamists, all of whom they denounce as terrorists. Libya Dawn’s religious-affairs minister, Mubarak Salah, for his part, sees IS-supporting jihadists in Derna as “just good young Muslims” and a welcome thorn in Dignity’s side. In the Tripoli hotel which has become Libya Dawn’s de facto base—the country’s governing institutions have mostly retreated into hotels, as if just visiting—an Islamist MP from Benghazi sips his macchiato and praises a recent car-bomb which targeted the government in the east. Libya Dawn’s national security adviser, Yusuf Dawar, who wears a tie, breeches and a deerstalker supposedly to enhance his appeal to potential supporters in America and Europe, threatens to take the war to Egypt if Mr Sisi continues to arm the east. Sleeping cells could strike, he warns, drawn from the 2m tribesmen of Libyan origin in Egypt.

Both sides were at first occupied with fighting pockets of opposition within their own territories—Islamist-led militias in Benghazi for Dignity, Zintan, an Arab town which sits on a crucial oil pipeline, for Dawn—rather than confronting each other. In September the UN’s special envoy, Bernardino Leon, who had shuttled across Libya dodging car-bombs, put together initial talks aimed at the creation of a national unity government in Ghadames, a dusty town near the Algerian border.

But as the pressure to reconcile built, hardliners turned their guns on each other. General Haftar bombed the airports in the west and the exit route to Tunisia. Libya Dawn pushed east towards Ras Lanuf; Libya’s main oil terminal, under the control of Dignity’s forces, was set aflame. General Haftar retaliated by sending his planes to bomb Misrata’s seaport and steel works.

The struggle over the Gulf of Sirte area, which holds Libya’s main oil terminals and most of its oil reserves, threatens to devastate the country’s primary asset. And in the Sahara, where the largest oilfields are, both sides have enlisted ethnic minorities as proxies: Libya Dawn has drafted in the brown-skinned Tuareg, southern cousins of the Berbers; Dignity has recruited the black-skinned Toubou. As a result a fresh brawl is brewing in the Saharan oasis of Ubari, which sits at the gates of the al-Sharara oilfield, largest of them all.

Oil production has fallen and become much more volatile; it can be 800,000 barrels one day and 100,000 the next. And oil is worth half as much as it was a year ago. The Central Bank is now spending at three times the rate that it is taking in oil money. The bank is committed to neutrality, but is based in Tripoli; last SeptemberTobruk’s parliament appointed its own governor for the bank, who accuses his opposite number of starving the east of currency. He says he is thinking of accepting oil payments for the use of his side alone. There are angry queues outside the few eastern banks still open. Ministers in Beida run their departments on short-term commercial loans. Some barely have phones to make calls on.

Broken up

Tripoli may have a little more access to cash, but is in bad shape in other ways. Fuel supplies and electricity are petering out. Crime is rising; carjacking street gangs post their ransom demands on Twitter. In Fashloum, a rundown neighbourhood near the city centre, residents briefly erected barricades to keep out a brigade of Islamists, the Nuwassi, who claim to be an anti-vice squad. “No to Islamists and the al-Qaeda gang” reads the roadside graffiti.

Meanwhile Libya’s ungoverned spaces are growing, and with some 6,000km of border the country’s problems are hard to quarantine. Each month 10,000 migrants set sail for Europe. Libyan arms in the hands of groups allied to al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb triggered the collapse of order in northern Mali two years ago; some of those who subsequently fought against the French there have now returned to Libya, where they are reportedly running jihadist training camps. On January 3rd, IS claimed to have extended its reach to Libya’s Sahara too, killing a dozen soldiers at a checkpoint on a jihadist transit route to the Sahel. The conflict is as likely to spread as to burn itself out.

Despite that risk, the Western powers which assisted in Mr Qaddafi’s downfall have since been conspicuous by their absence. Chastened by failure in Afghanistan and Iraq, they have watched from the sidelines as things have gone from promising to perturbing to bad to worse. President Obama washed his hands of Libya after Islamists killed his ambassador, Chris Stevens, in Benghazi in September 2012.

Italy, the former colonial power, is the last country to have a functioning embassy in Tripoli. Turkish Airlines, the last foreign airline still flying to Libya, suspended flights on January 6th; Egypt and Tunisia have closed land borders. Even under Qaddafi the country did not feel so cut off. But neither that isolation nor a UN arms embargo have stopped parts of the outside world from playing an unhelpful role. Dignity is supported not just by Mr Sisi but also by the United Arab Emirates, which has sent its own fighter jets into the fray as well as providing arms. The UAE’s Gulf rival, Qatar, and Turkey have backed the Islamists and Misratans in the west.

Mr Leon is still trying to get talks started. If oil revenues were to be put into an escrow account, overseas assets frozen and the arms embargo honoured he thinks it might be possible to deprive fighters of the finance that keeps them fighting and force them to the table. He would also like to see the 2011 no-fly zone reimposed, though this is unlikely given Russian and French opposition in the Security Council. If a ceasefire could be reached, Mr Leon has a fledgling plan developed with the Italians for thousands of UN peacekeepers to maintain it. But he admits with a grimace that such a positive outcome is “wishful thinking”. Following a meeting with Mr Leon in Cairo, the Tobruk parliament’s speaker, Aguila Salah Issa, wonders whether the time for reconciliation has passed.

Mr Leon says that, in retrospect, “treating Qaddafi’s Libya as a country with a political culture like Tunisia, whose institutions could manage themselves, was a mistake”. When tensions which initially erupted over power and money were reinforced by ideology, regionalism and ethnicity, the brave hopes of the revolution had nothing to fall back on. The assembly elected in February 2014 to draft a constitution, one of the few unitary institutions left in the country, struggles on in Beida despite boycotts and deep divisions between its members. There is something noble about that; there is much that is forlorn.