Dr. Nasser H. Saidi

“If we educate a boy, we educate one person. If we educate a girl, we educate a family – and a whole nation.” An African Proverb.

October 11 marked the International Day of the Girl Child, highlighting the marginalization of girls and women everywhere. Despite much improvement in women’s status over the last few decades, women still own only 1 percent of the world’s wealth, earn only a 10 percent share of global income, and occupy just 14 percent of leadership positions in the private and public sector, despite making up more than half of the world’s population.

In the Arab world, women have the lowest rates of female labour force participation globally: 26 percent compared to a global average of 52 percent. They face insuperable barriers, discrimination, legal and regulatory hurdles, lack of economic opportunities, poor working conditions, and the absence of the institutional, societal support needed to leverage them into economic and public life. As such, the real “Arab Spring” is about the necessary paradigm shift, the transformation of women’s role in economic development and their empowerment.

Women & Economic Development

What is the rationale behind the empowerment of women? There is a two-way relationship between economic development and women’s empowerment, i.e. enabling women to access the constituents of development: health, education, earning opportunities, rights, and political participation. While economic development helps bring about women’s empowerment, empowering women brings about changes in choices and decision-making, which have a direct, positive impact on development.

Poverty and lack of opportunity breed inequality between men and women, so when economic development reduces poverty, the condition of everyone, including women, improves. But economic development alone does not bring about parity between men and women. Policy action is necessary to achieve equality between genders. Such policy action is unambiguously justified because empowerment of women also stimulates further development, starting a virtuous cycle. In the other direction, continuing marginalization and discrimination against women hinders development. The bottom line is that empowerment can and does accelerate development.

Women Are Better Educated & Healthier

Arab countries have made rapid progress in reducing gender gaps in education and longevity, and in lowering fertility levels. Among the developing regions of the world,MENA achieved the largest decline (59 percent) in the maternal mortality ratio between 1990 and 2008. Over the past decade, female school enrollments in the MENA have grown faster than male enrollments, with the female-to-male ratios currently in the high nineties and women are now more likely than men to attend university. They perform better at all levels of education. With its significant investment in women’s education, Arab countries increased women’s productive potential and capacity to earn. But the low levels of female participation in economic activity means that the region is not realizing the return on its investment. The human capital of women is being wasted.

Wasting the Human Capital of Women

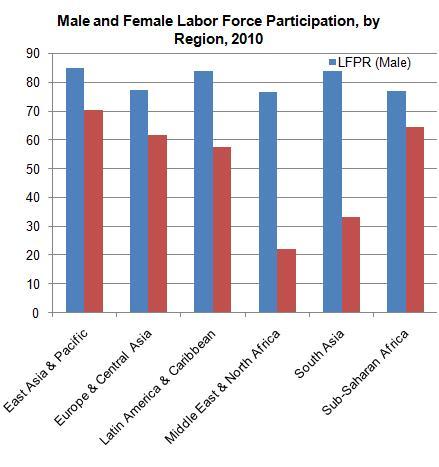

Arab women have the lowest labour force participation rate (LFPR), only 22 percent, of any region in the world and the largest gap with men’s participation (see chart)! As a consequence the Arab region has the lowest overall LFPR: only 54 percent compared to a world rate of 65 percent (excluding MENA).

When employed, women tend to be well or even over-represented in the public sector: on average 28 percent of employed women work in the public but this rises to more than 80 percent in Qatar, UAE and Saudi Arabia. By contrast, women’s share of employment in the private sector is very low, averaging only 20 percent and less than 10 percent in Saudi Arabia, Syria, Palestinian Authority and Yemen. Arab women also have a lower level of involvement than men in entrepreneurial activity: on average 8.1 percent of adult women are nascent entrepreneurs or already own a young business that is less than 42 months old, compared to an average of 16.1 percent for men. In the Gulf region, even within the self-employed category, working men were six times more likely to be self-employed than working women!

Why the poor performance? Barriers to entry are numerous. Purportedly “protective” labour laws make it costly for the private sector to actively hire women. Employment in the public sector is not a “good incubation environment” for skills generation for transition to the competitive private sector! The lack of access to finance is another barrier. Globally, 47 percent of women and 55 percent of men have an account at a formal financial institution. The gap is wider in the MENA region: only 13 percent of women as opposed to 23 percent of men have an account. Absent a bank account, it is difficult to enter the formal economy and grow an SME!

To add to the disincentives, working women face the highest unemployment rates. The factor that spikes the total unemployment rate in the Arab region is the high female unemployment rate of 17.4 percent (ILO, 2012). Arab women are on average twice as likely as men to be unemployed. Also, the younger and the more highly educated the higher the unemployment rate amongst women!

Increasing Women’s Participation Can Radically Change Arab Economies

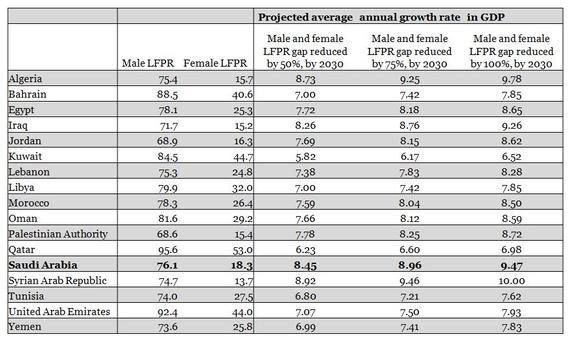

A rough calculation indicates that if female LFPRs were at the same level as in the OECD (60 percent), the MENA region could drastically increase GDP by 20 to 25 percent.The accompanying table shows that we could achieve a near doubling in growth rates if women participated at similar rates as men. The fastest growth rates would be achieved by those countries with the lowest female participation rates. Iraq and Saudi Arabia could grow at 8 to 9 percent per annum by 2030 and Jordan by 7 to 8 percent. The economic performance and landscape of the Arab world would be transformed through the contribution of the skills, talent, labour and entrepreneurship of women. However, this will not happen through the wave of a magic wand. We need to invest and do things differently. We have to change laws, institutions and regulations that marginalize and discriminate against women and youth.

Source: author’s calculations

Change Laws & Regulations That Discriminate Against Women

In national vision documents and national development policy documents, Arab governments usually make reference to the importance of women’s empowerment and their increased role in the economy as necessary for equitable local and regional development. However, gender discrimination in MENA is typically codified in law, frequently in discriminatory family laws or civil codes, restrictions on resources and entitlements, son biases and restricted civil liberties. In many countries, women must obtain permission from a male relative, usually a husband, father or brother, before seeking employment, requesting a loan, starting a business, or even travelling. Social institutions in the Arab countries embody some of the highest levels of discrimination in the world (map below). As is clear from the map and the examples of Turkey, Malaysia and Indonesia, this is not a matter of Islam, but a matter of culture. It will take and effort to change mind sets.

Similarly, the World Bank’s important survey on “Women, Business & the Law” highlights that the MENA region is the one where women face the highest number of restrictions in their capacity to act (Chart below). It also found that the greater the lack of legal parity is associated with lower labour force participation by women (both in absolute terms and relative to men) and lower levels of women entrepreneurship. The report reveals that in the Arab countries, explicit legal gender discrimination was most common, both in accessing institutions and in using property; there is a differentiation in inheritance laws; there are limits on the industries in which women may work relative to men. In nine of the 14 MENA there are four or more legal differentiations that hinder women’s economic rights, activity, mobility and participation.

What Next?

The waste and underutilization of female human capital and capacity is a major drag on the performance and growth prospects of Arab economies. Post-Arab firestorm, empowerment of women should be a major priority on the region’s transformational and reform agenda. Making greater use of women workers increases growth and productivity, not only because women jobseekers typically have higher than average education, but also because this can increase mobility across sectors and jobs. By bringing in new skills and talents we increase the diversification of economic activity. The priority should be for an affirmative action program that actively promotes women and reverses marginalization and discrimination. We need corrective policies, laws and quotas. Reforms are necessary in the legal framework to support women’s rights, including property, access to finance and mobility. Removing the barriers to women’s economic participation can be a game changer for the region. This period of transformation requires the contribution of women towards nation building: their increased participation in politics, parliament, and cabinets and even simply as voters can bring about a dramatic change in the way our civil societies are structured.